In the next few years, Mars will be visited by three new rovers, the Perseverance, Tianwen-1, and Rosalind Franklin* missions. Like their predecessors - Pathfinder and Sojourner, Spirit and Opportunity, and Curiosity* - these robotic missions will explore the surface, searching for evidence of past and present life. But even after years of exploring, an important question remains: where is the best place to look?

To date, all attempts to find evidence of life on the surface have yielded nothing, owing to the fact that the Martian environment is extremely cold, desiccated, and irradiated. According to a new study by an international team of researchers led by Cornell University and the Centro de Astrobiología in Madrid, the Atacama desert in the mountains of Chile could hold the answer.

Located in northern Chile and ranging in elevation from 2,400 meters (7,900 feet) to 4,800 m (15,700 ft), the Atacama plateau desert is the driest region on the planet. Because of its elevation and negligible cloud cover, this region is an ideal place for astronomical studies, which is why the European Southern Observatory (ESO) operates three major observatories there - La Silla, Paranal, and Llano de Chajnantor.

These facilities host some of the most impressive telescopes in the world, like the TRAPPIST telescope, the Very Large Telescope (VLT), the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) - and coming soon, the ESO's highly-anticipated Extremely Large Telescope (ELT). In addition, Atacama's natural aridness makes it a good analog for Mars, where conditions are also extremely dry.

For some time, scientists have known that Mars wasn't always this way. Roughly 4 billion years ago, it had a thicker, warmer atmosphere that allowed for liquid water to flow on its surface. Unfortunately, Mars slowly lost its atmosphere over the course of eons, causing most of this water to be lost to space. What water remains there today is largely confined to the polar ice caps or hidden underground.

If life once existed on Mars, it too would have retreated underground and could still be there today. For this reason, Dr. Armando Azua-Bustos of the Centro de Astrobiologí and Dr. Alberto G. Fairén (a visiting scientist at Cornell and a NASA Non-Resident Affiliate Scientist) led an international team to study wet clay deposits beneath the surface.

These deposits, located about 30 cm (1 foot) underground, were found to contain diverse populations of microbes. What's more, they are similar to clays found under the surface on Mars, which would be easily accessible to future rovers. As Fairén, who was a corresponding author on the study that appeared in Nature Science Reports, explained to the Cornell Chronicle:

"The clays are inhabited by microorganisms. Our discovery suggests that something similar may have occurred billions of years ago – or it still may be occurring – on Mars. If microbes still exist today, the latest possible Martian life still may be resting there."

The clay layer was excavated in the Yungay region of the Atacama desert, a possible and previously unreported habitat for microbial life. It was here that they found at least 30 species of salt-loving of metabolically-active bacteria and archaea (single-celled organism). This discovery reinforces the theory that Mars may have had similar protected habitable niches beneath its surface, particularly during the first billion years of its history.

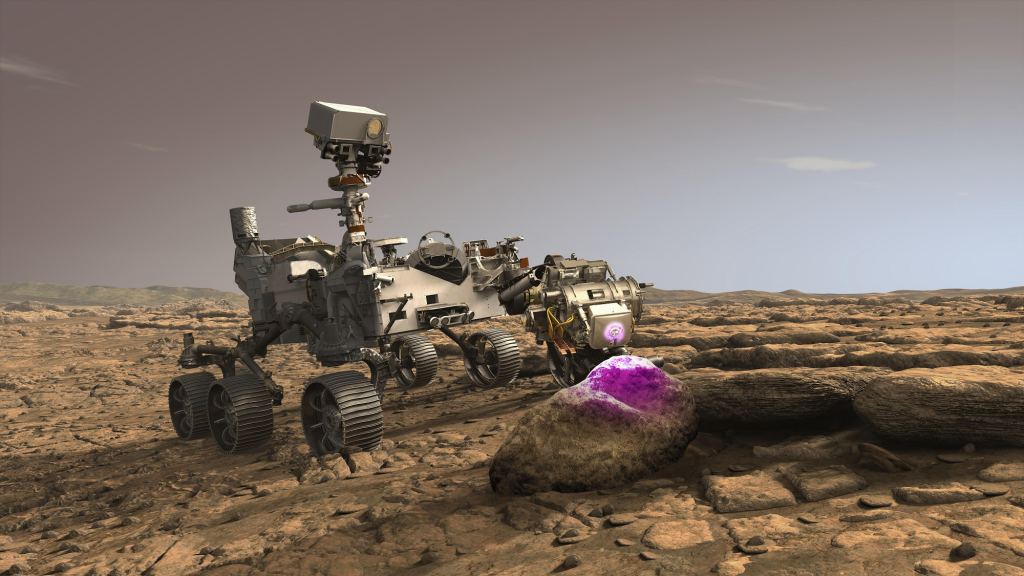

NASA's Perseverance rover and the rover element of China's Tianwen-1 mission will both land on Mars in February 2021. The ESA's *Rosalind Franklin* rover, whose launch was postponed to 2022 (due to the COVID-19 pandemic), will arrive by 2023. All three of these missions are tasked with searching for biomarkers in subsurface clays deposits, which will be easily accessible to them.

Herein lies the value of using Mars-analog environments on Earth to investigate findings that are predicted on Mars. As Fairen summarized:

"This paper helps guide the search. to inform where we should look and which instruments to use on a search for life. That’s why clays are important. They preserve organic compounds and biomarkers extremely well and they are abundant on Mars."

In the next few years, scientific investigations on Mars will reach a whole new level. From this, one of two things will result: humanity will either have compelling evidence that life exists beyond Earth, or we won't. Either prospect demands that we keep investigating so that we may learn all we can about where and how life emerged in the Solar System.

Further Reading: Cornell Chronicle*, Nature Science Reports*

Universe Today

Universe Today