It’s always a sad day when a mission comes to an end. And it’s even sadder when the mission never really got going in the first place.

That’s where we’re at with NASA’s InSight lander. The entire mission isn’t over, but the so-called Mole, the instrument designed and built by Germany’s DLR, has been pronounced dead.

The Mole is, of course, the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3). It’s an instrument designed to measure the heat flowing from the Martian interior to the surface. The entire InSight mission (Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy, and Heat Transport) was focused on discovering more about the interior of Mars.

HP3 is probably the most important and complicated instrument on the lander. So losing it is a big blow to science. But it’s implementation was always going to be tricky, and mission designers knew that.

“This is why we take risks at NASA – we have to push the limits of technology to learn what works and what doesn’t.”

Thomas Zurbuchen, Sssociate Administrator for Science, NASA.

The Mole’s job was to burrow into the Martian surface to a depth of up 5 meters. A tether would connect the Mole to the lander, and along that tether are evenly spaced heat sensors. By studying the thermal properties of the interior of the planet, scientists could’ve learned a lot about its geologic history.

But getting the instrument into the ground was always going to be tricky. The Mole is a self-hammering instrument that was designed to slowly work its way down into the surface. The mission’s weight and energy limitations meant that a more powerful, forceful way of driving the instrument into the ground were not feasible.

From the beginning of its deployment in March 2019, the Mole has faced problems. At first it made some progress, but after penetrating a few centimeters it stopped. Initially, mission personnel thought it was blocked by a rock.

Universe Today has covered the Mole’s saga in a series of articles. There were signs of progress and signs of despair along the way. But over time it became clear what prevented the Mole from fulfilling its potential.

The surface of Mars where the InSight lander is situated is covered in a soil type called duracrust. It’s a compacted layer of soil that doesn’t fall back into the Mole’s hole as it works its way downward. That’s a problem.

The Mole relies on friction between itself and its surroundings. But since duracrust is too solid and won’t flow into the hole, it doesn’t provide the required friction.

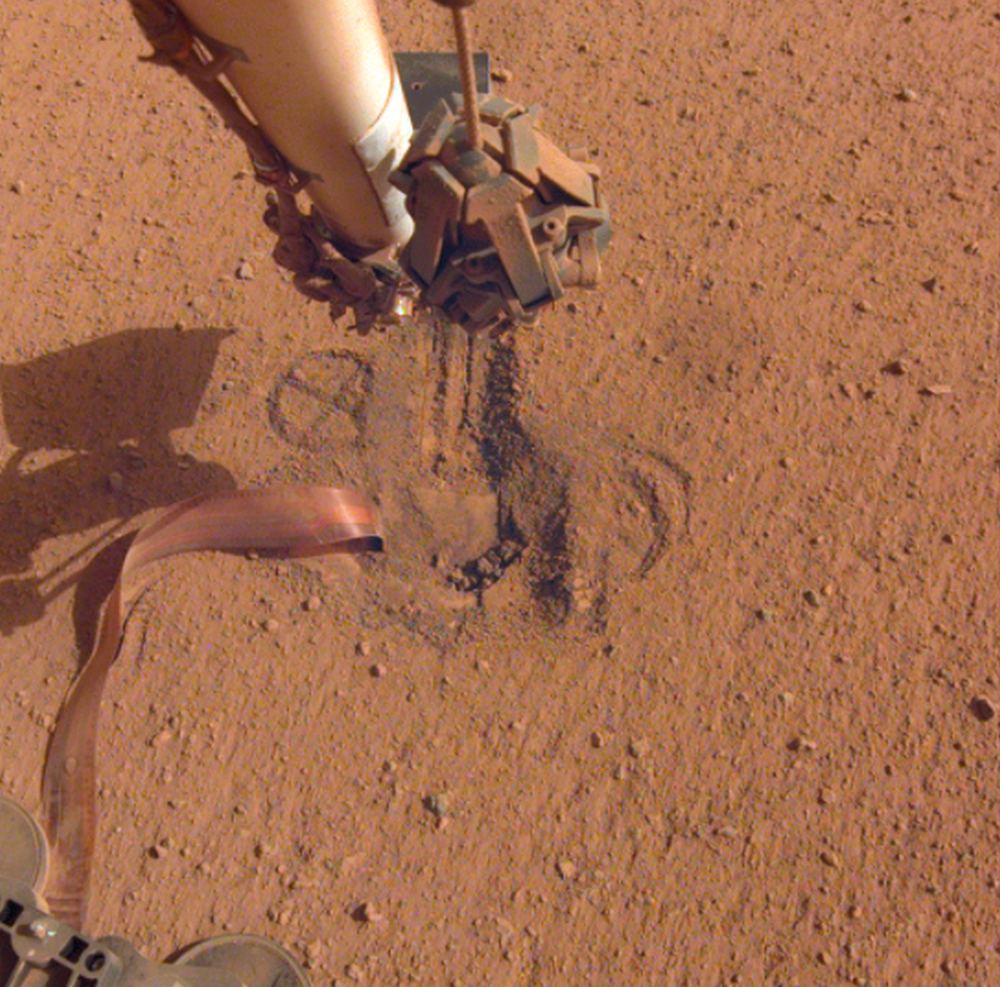

Mission personnel tried everything to supply the missing friction. They used the instrument arm scoop to press down on the Mole. They used it to provide sideways pressure on the Mole. And they used it to try to scoop the needed soil into the hole. Each method provided some hope, but in the end, the Mole couldn’t get deep enough to do science.

Now the Mole has been declared dead, after 500 final, and ultimately futile, hammer strokes in January.

“We’ve given it everything we’ve got, but Mars and our heroic mole remain incompatible,” said HP3’s principal investigator, Tilman Spohn of DLR.

But all is not lost.

The lander’s other instruments, including its seismometer, are still working. So the mission still has scientific value. And though the mole failed, despite the best efforts of people at NASA and the DLR, failure can plant the seeds of future success.

“Fortunately, we’ve learned a lot that will benefit future missions that attempt to dig into the subsurface,” said Spohn.

This is the first time a mission has attempted to dig into the Martian surface like this, so the whole endeavour was in uncharted territory. There’s was no way to know what would happen with the Mole with any certainty. But it’s been a fascinating episode, as members of the Mole’s team tried to figure out a way forward.

“We are so proud of our team who worked hard to get InSight’s mole deeper into the planet. It was amazing to see them troubleshoot from millions of miles away,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for science at the agency’s headquarters in Washington. “This is why we take risks at NASA – we have to push the limits of technology to learn what works and what doesn’t. In that sense, we’ve been successful: We’ve learned a lot that will benefit future missions to Mars and elsewhere, and we thank our German partners from DLR for providing this instrument and for their collaboration.”

Other missions have given us clear looks at the Martian surface. Mission designers thought that the Mole’s hammering design would give it the best chance of fulfilling its mission. From appearances, it was the right call. But the duricrust was a surprise and proved to be too large an obstacle to overcome. Though it failed, the whole enterprise was unprecedented from the start.

“The mole is a device with no heritage. What we attempted to do – to dig so deep with a device so small – is unprecedented,” said Troy Hudson, a scientist and engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California who has led efforts to get the mole deeper into the Martian crust. “Having had the opportunity to take this all the way to the end is the greatest reward.”

The other parts of InSight’s mission are ongoing. The SEIS (Seismic Experiment for Internal Structure) is still busy measuring Marsquakes and other events, and the RISE (Rotation and Interior Structure Experiment) instrument is still working to find out the size of Mars’ iron-rich core. The lander’s weather station is still working, too.

InSight was launched in May 2018, and landed on Mars on November 26th 2018. The Mole was deployed on February 12th, 2019. The mission has been extended to December 2022.

I have to be honest: I thought this was a poorly-conceived idea and instrument right from the start. Not only would it be unpredictable and nearly impossible for a non-hammering drill to burrow down in all but the sandiest terrain, but I found the entire scientific premise behind it highly doubtful.

I don’t think that digging into a few meters of rock and soil will tell NASA any more about Mars’s interior than digging into a few meters of Nebraska top soil will tell us about Earth’s core.

Least surprising scientific development ever!

I agree. They came up with an elegant solution that simply could not perform.

They should have just dropped something from the final stage above the planet above its intended landing zone.

Shaped like a arrowhead, tipped with some sort of super-tough carbide alloy and weighed to ensure the pointed tip aimed downward, and properly insulated to prevent damage to the probe and the hardware needed to communicate remotely with the lander, it would have easily penetrated the surface of Mars.