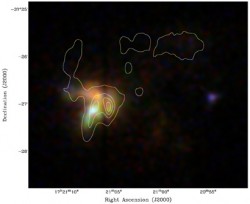

XMM-Newton has just released this beautiful image of a supernova remnant and its companion neutron star. To be more accurate, it didn’t “discover” the object, remnant G350.1-0.3 had previously been mistaken to be a distant galaxy. The X-ray observatory has reclassified the object as a Milky Way binary system with one neutron star and the remnant of a young supernova. A wonderful tale about mistaken identity and re-opening a cosmic cold-case, a thousand years after the event…

G350.1-0.3 is special in so many ways. Many astronomers have dubbed this object a “celestial gem” because it is a strikingly beautiful X-ray observation. Apart from its looks, this re-classification by XMM-Newton is very significant to astrophysicists studying the chemical composition, formation and cause of a supernova event. This said, G350.1-0.3 isn’t any normal supernova remnant.

Supernova remnants are usually observed as symmetrical, expanding “bubbles” of hot stellar plasma. Generally, as a massive star finally dies, the explosion should send material out equally in all directions, it is for this reason they are usually easy to distinguish from background galaxies. G350.1-0.3 doesn’t obey this rule; some outside influence had given the remnant a rather odd shape. In the 1980’s, this celestial object was observed in high-resolution images and the knotted gases in the image gave astronomers the impression that the object was “just another distant galaxy” and then forgotten about. That was until NASA’s X-ray observatory XMM-Newton re-examined the object. It quickly became apparent that it was a supernova remnant in the Milky Way, not a far-flung galaxy.

This is also a very young supernova remnant. According to Bryan Gaensler and Anant Tanna, from the University of Sydney, who used XMM-Newton to not only prove appearances can be deceptive, but also that the remnant is only 1000 years old. Finding such a young remnant is extremely valuable. “We’re seeing these heavy elements fresh out of the oven,” said Gaensler when referring to G350.1-0.3. Generally, any supernova remnant over 20,000 years old is pretty much the same as another remnant of that age. Finding one so young, so bright and so close gives astrophysicists a prime opportunity to understand the dynamics of a supernova only a short period of time after it blew.

But why the strange shape? It turns out the supernova detonated right next to a dense cloud of gas about 15,000 light-years from Earth. The cloud strongly influenced the expanding gas, preventing the hot matter from expanding uniformly in all directions. This is rare, misshapen supernova remnants aren’t seen very often.

The supernova may have occurred around the time when William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066; perhaps the Battle of Hastings was being waged when the explosion happened overhead. Unfortunately, it may not have been witnessed:

“The X-ray data tell us that there’s a lot of dust lying between it and Earth. Even if you’d been looking straight at it when it exploded, it would’ve been invisible to the naked eye.” – Bryan Gaensler

This is some tremendous detective work by the Australian team and the XMM-Newton telescope, ensuring G350.1-0.3 will never be forgotten again. I just hope they give it a better name soon!

Source: ESA

I think that when it comes to writing an article about something with such an unwieldy name, much like how corporations and associations are spelled out and then given an acronym in parentheses, we should give the proper name, and then give it a nickname for the article or post.

I.e.:

G350.1-0.3 is special in so many ways. Since it looks like a diver crouching to do a double backflip with a half twist from the 10-meter platform, we’ll call it Greg for the rest of this post.

…

This said, Greg isn’t any normal supernova remnant.

See? I got the idea from Colonel Shepherd from SG:A.

PS: I’m so glad we have these other-spectrum telescopes in orbit finding these things. 🙂

I wonder what radius around this SNR would be prime to search for faint visible-light echoes, especially given its young age and deep direct obscuration from Milky Way dust?

very good