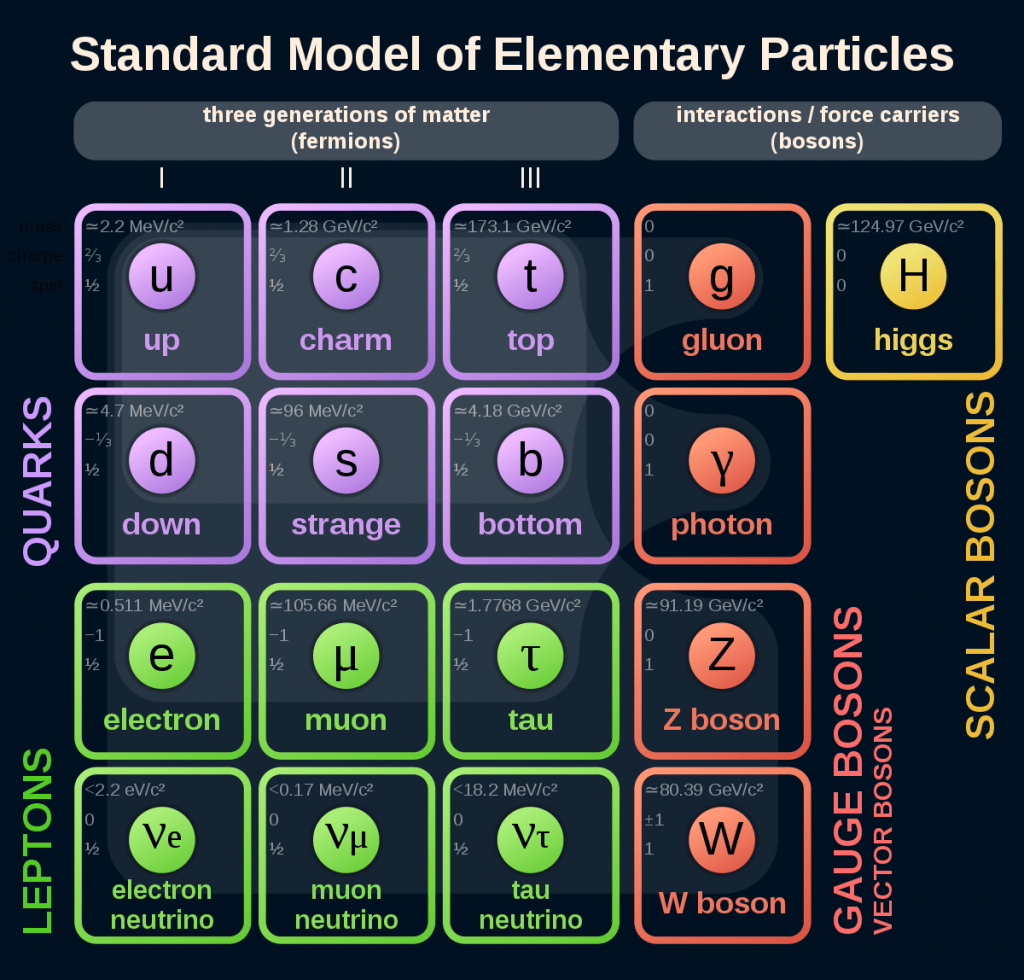

We don't know what dark matter is. We do know what it isn't, and that's a problem. Matter is made of elementary particles, from the quarks and electrons that make up atoms and molecules, to primordial neutrinos spread throughout the cosmos. But none of the known elementary particles can comprise dark matter, so what is it?

Several ideas have been proposed, from Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs), to hypothetical particles known as axions, to tiny black holes. But so far, the evidence doesn't really support these ideas. So astronomers have looked to another theoretical particle known as sterile neutrinos.

Neutrinos are a form of dark matter, because they have mass, and weakly interact with light. But neutrinos have such a small mass and high energy that they move through the universe at nearly the speed of light. For this reason, they are known as hot dark matter. We know from observations that dark matter is mostly cold, meaning that dark matter particles must move relatively slowly. So while neutrinos make up a small part of dark matter, most of it must be something else.

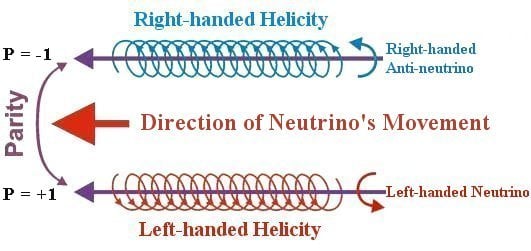

There are three known types or flavors of neutrinos, and they have some rather strange properties. One of these strange properties is their helicity. Elementary particles have spin, and when they travel the spin is either oriented along their direction of motion (right-handed helicity) or opposite to their motion (left-handed helicity). Most particles can have either helicity depending on the interaction, but the helicity of neutrinos is always left-handed. We aren't entirely sure why, but we do know that if right-handed neutrinos exist they wouldn't interact with regular matter through the electroweak force. They would only interact with matter gravitationally, so they are known as sterile neutrinos.

If sterile neutrinos exist, and they are just regular neutrinos with right-handed helicity, then they would be hot dark matter and not the cold dark matter we're looking for. But there are some theories where sterile neutrinos are much more massive than regular neutrinos. These heavy sterile neutrinos could comprise dark matter. That is if they exist.

If there are heavy sterile neutrinos out there, they could be discovered by their radioactive decay. Heavy particles can decay into lighter particles over time, so it's possible that sterile neutrinos can decay to their lighter counterparts, emitting x-ray photons in the process. In an effort to discover these x-ray emissions, a team combed through data from the Chandra X-Ray Observatory. They didn't find any evidence of sterile neutrinos. Their results weren't strong enough to entirely rule out the idea, but it does narrow down the theoretical candidates a bit. Specifically, the study places a hard limit on how sterile neutrinos can decay if they exist.

We still don't know what dark matter is. Studies like this might seem disappointing, but they play an important role. By narrowing down our options, they force us to focus on more viable dark matter candidates. We've learned something more, but for now, we are still in the dark.

Reference: Sicilian, Dominic, et al. " Probing the Milky Way’s Dark Matter Halo for the 3.5 keV Line." *The Astrophysical Journal* 905.2 (2020): 146.

Universe Today

Universe Today