One of the oldest, deepest, and largest impact craters on the Moon provides a window into the history and makeup of our celestial companion, and needs to be studied in more detail, says a team of lunar scientists. The South Pole-Aitken Basin on the Moon formed from a gigantic impact about 4.3 billion years ago. Scientists say a more detailed analysis of this area will help refine the timeline of events in the Moon’s development, as well as help explain the dramatic differences between the lunar nearside and farside.

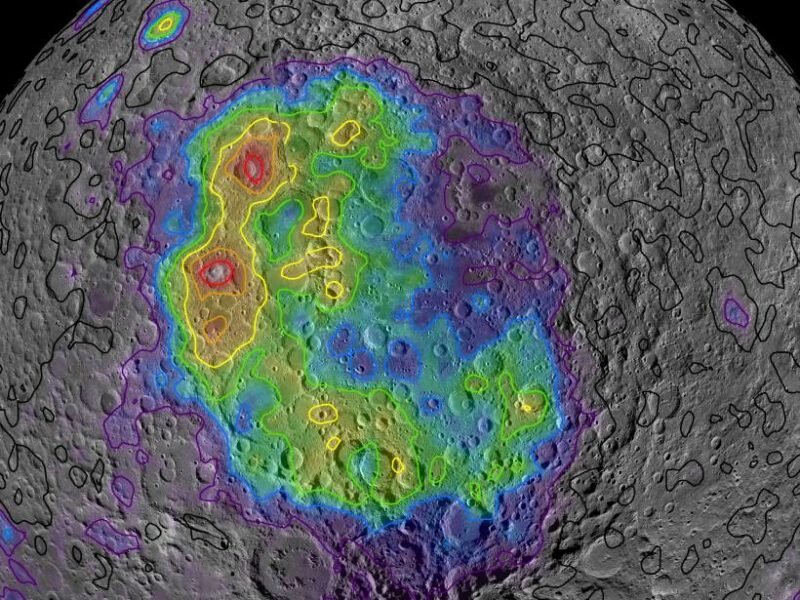

In a new paper, Daniel Moriarty of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and colleagues used a combination of computer models, remote sensing data, and data from Apollo lunar samples to help refine the timeline of the Moon’s development. They focused on data from the South Pole-Aitken basin, a 1,200-mile-(1,900 km)-wide crater that formed when a large impactor with a heavy metal core smashed into the lunar surface billions of years ago. Many lunar scientists consider the basin as one of the best natural laboratories for studying catastrophic impact events. With depths between 6.2 and 8.2 km deep, it is one of the largest known impact craters in the Solar System.

In their paper, the team looked at how impacts mix and combine various materials into various layers, and how they could use this information to define the timeline for the Moon’s development. Early in the Moon’s history, the Moon’s layering was shaped by an early global melting event known as the Lunar Magma Ocean, and as the magma ocean solidified, dense minerals sank to form the mantle, while less?dense minerals floated to form the crust.

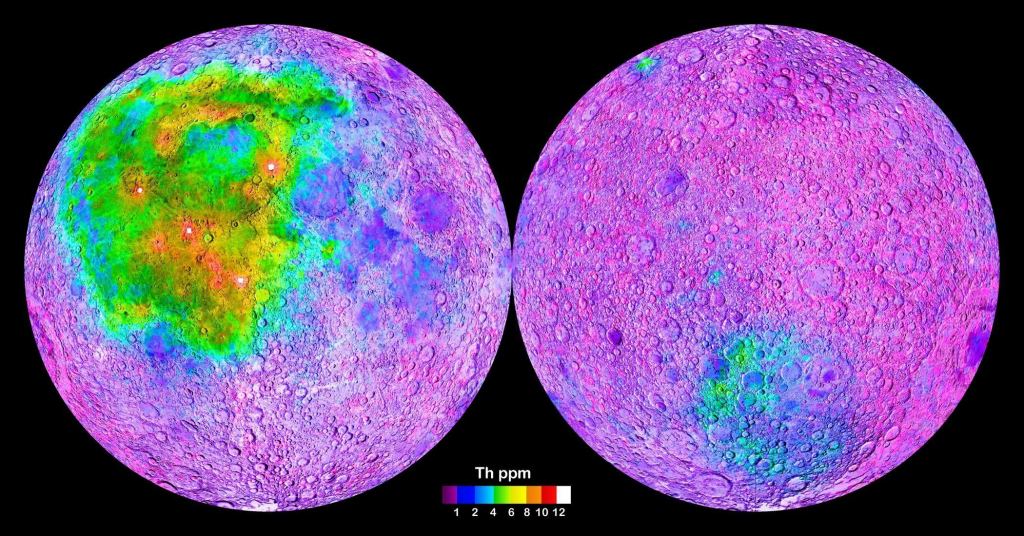

One of the dense “dregs” that sunk to form the early molten mantle was thorium, a metallic, radioactive chemical element that is also found in trace quantities on Earth. Data from various missions, including the Lunar Prospector, shows widespread areas of thorium on the lunar nearside, as well as a small area of enriched thorium on the lunar farside, within the South Pole-Aitken Basin.

To explain the differences between the lunar nearside and farside in terms of crustal thickness and evidence of volcanic activity, earlier theories suggested that thorium-rich dregs occurred only on the nearside. However, Moriarty and team said their new results demonstrate that these substances were ejected by the giant impact on the Moon’s farside. This observation implies that at the time of the impact, thorium-rich material must have been globally distributed.

The paper proposes that before the Lunar Magma Ocean was fully cooled, then came the impact to the Moon’s south pole. The team’s computer model simulations showed that the impact was energetic enough to eject the deep “dregs” from the mantle. Their simulated ejecta’s splash pattern corresponds to areas of the lunar surface known to be rich in thorium.

“We demonstrate that the Moon’s largest and oldest impact basin excavated material from this dense, thorium?rich layer before it sank,” the team wrote. “The exposed material was then diluted and obscured by four billion years of impact cratering and volcanic eruptions. However, we identify several pristine exposures created by recent craters.”

The team said that the impact basin also melted rocks from greater depths than the rocks it ejected. These melted rocks exhibit a much different composition. This indicates that the lunar upper mantle included two compositionally distinct layers that were exposed in different ways by this large impact event. These results have important implications for understanding the formation and evolution of the Moon.

The South Pole Aitken Basin offers a unique place to study the Moon, mostly because so little is known about it. NASA’s GRAIL mission mapped the Moon’s gravity and discovered an anomaly in the basin: a massive chunk of dense material is buried there, further evidence that the Moon’s structure is not uniform, and that denser materials can be spread throughout the subsurface. Then there’s the Moon’s KREEP terrain, a deposit of elements that are decaying radioactively and encouraged that part of the Moon to remain volcanic long after the rest of the Moon had cooled.

To learn more, Moriarty and colleagues identified potential targets in the Basin future sampling missions focusing on ejected material, which could give us an even clearer picture of the Moon’s early mantle.

Further reading: Eos press release

Just out of curiosity, while the distribution of thorium in/around the South Pole Aitken Basin does match the prediction, that in the Procellarum Basin doesn’t. I remember a story a few years back about granite being found on the Moon (a rock we usually associate with the fractionation of basalt in the presence of water). There are at least two locations in the Procellarum that are really bright in the image that match those locations of granite. Granite formation concentrates thorium, potassium and uranium, so is it likely in at least some of the areas, the detection of thorium is to do with long-lasting volcanism associated with the rise of granitic rocks, rather than to do with impact digging down into thorium-rich rock?