All across the Martian surface, there are preserved features that tell the story of what Mars once looked like. These include channels that were carved by flowing water, delta fans where water deposited sediment over time, and lakebeds where clay and hydrated minerals are found. In addition to telling us more about Mars' past, the study of these features can tell us about how Mars made the transition to what it is today.

According to new research led by Brown Ph.D. student Ben Boatwright, an unnamed Martian crater in Mars southern highlands showed features that indicate the presence of water, but there is no indication of how it got there. Along with Brown professor Jim Head (his advisor), they concluded that the crater's features are likely the result of runoff from a Martian glacier that once occupied the area.

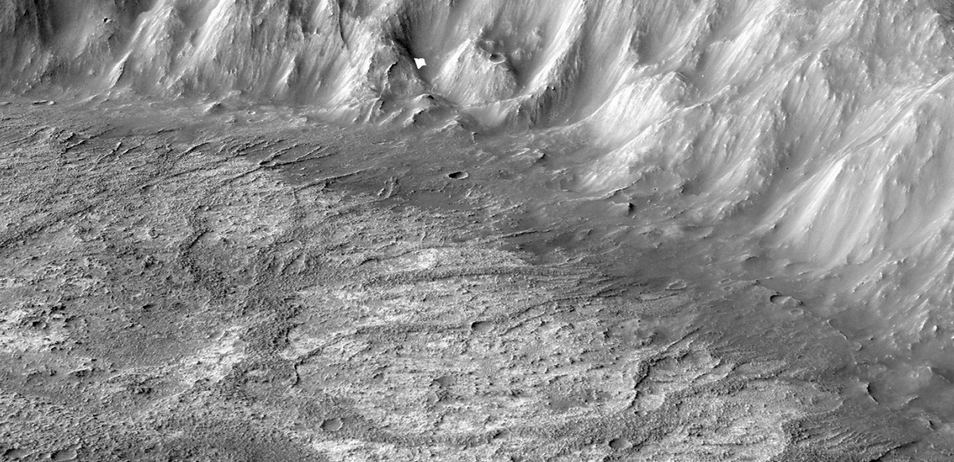

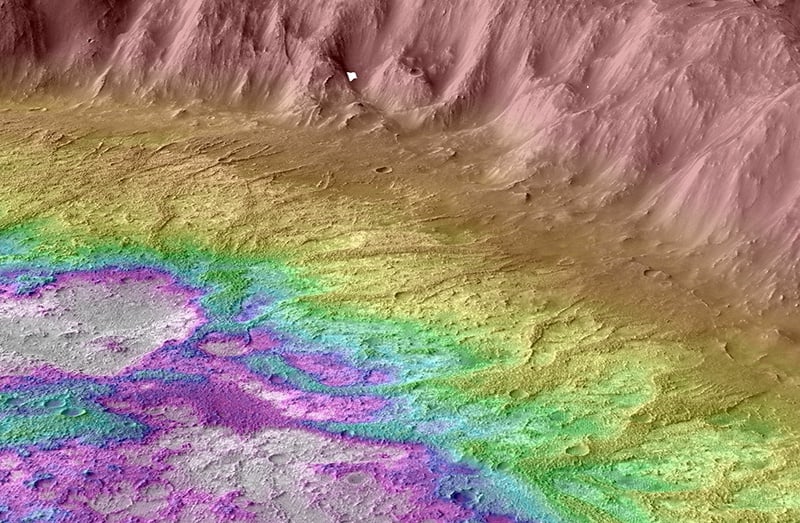

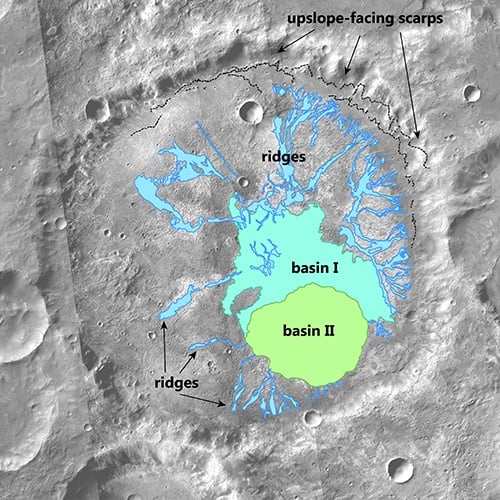

The crater they examined is located in Mars' southern highlands, measures 54 km (33.5 mi) in diameter, and dates to the Noachian Era on Mars (ca. 4.1 to 3.7 billion years ago). Based on images obtained by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), Boatwright and Prof. Head mapped out the crater's floor and found features that are unmistakable indications that stream beds and ponds once existed there.

However, this crater also showed no evidence of inlet channels where water could have flown into the crater and no evidence of groundwater activity where it could have percolated up from below. As Boatwright said in a recent Brown University press release:

"This is a previously unrecognized type of hydrological system on Mars. In lake systems characterized so far, we see evidence of drainage coming from outside the crater, breaching the crater wall and in some cases flowing out the other side. But that’s not what is happening here. Everything is happening inside the crater, and that’s very different than what’s been characterized before."

The features are known as inverted fluvial channels, which are formed when water flows across rocky surfaces, leaving coarse-grained sediment inside the channel it carves. When these sediments interact with water, they can form minerals that are harder than the surrounding rock. After eons of erosion has worn these rocks down, the mineralized channels will remain as raised and branching ridges.

To determine how the water could have arrived there, Boatwright and Head began by ruling out groundwater systems since the crater lacked the telltale sapping channels that form in their presence. These features generally appear as short, stubby channels that have no tributaries, which are starkly different from the dense, branching networks of inverted channels they observed.

They also noted the presence of a distinct set of ridges that face upward toward the crater wall, which bear a striking resemblance to ridges on Earth that formed at the edges of glaciers. With these observations combined, they concluded that the crater's inverted channels were created by a glacier-fed system that slowly deposited sediment and minerals over time.

In addition to being the first of its kind to be discovered, this new hydrological system could also provide vital clues about the early climate of Mars. Scientists have known for some time that Mars was once warm enough to support liquid water on its surface. However, it is still unclear whether the climate was mild enough for this water to flow continuously, or if it was mostly glacial with intermittent periods of melting.

In the past, scientists have conducted climate simulations that suggest that early Mars experienced temperatures that rarely peaked above freezing. However, there has been little geological evidence to support these models. As Boatwright explained, this new evidence of ancient features that are associated with glacial runoff could change that.

"The cold and icy scenario has been largely theoretical — something that arises from climate models. But the evidence for glaciation we see here helps to bridge the gap between theory and observation," he said. "I think that's really the big takeaway here."

"We have these models telling us that early Mars would have been cold and icy, and now we have some really compelling geological evidence to go with it," added Head. "Not only that, but this crater provides the criteria we need to start looking for even more evidence to test this hypothesis, which is really exciting."

What's even more exciting is that this crater is not a one-of-a-kind find. During the 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (which took place online from March 15th–19th), Boatwright presented subsequent research that has revealed more than 40 other craters that appear to have similar features. Their previous research was published in a paper that appeared in the March 12thissue of The Planetary Science Journal.

*Further Reading: Brown University*, The Planetary Science Journal

Universe Today

Universe Today