Underneath its shell of ice, the globe-spanning ocean of Enceladus isn't sitting still. Instead, it might possibly host massive ocean currents, driven by changes in salinity.

Ocean world

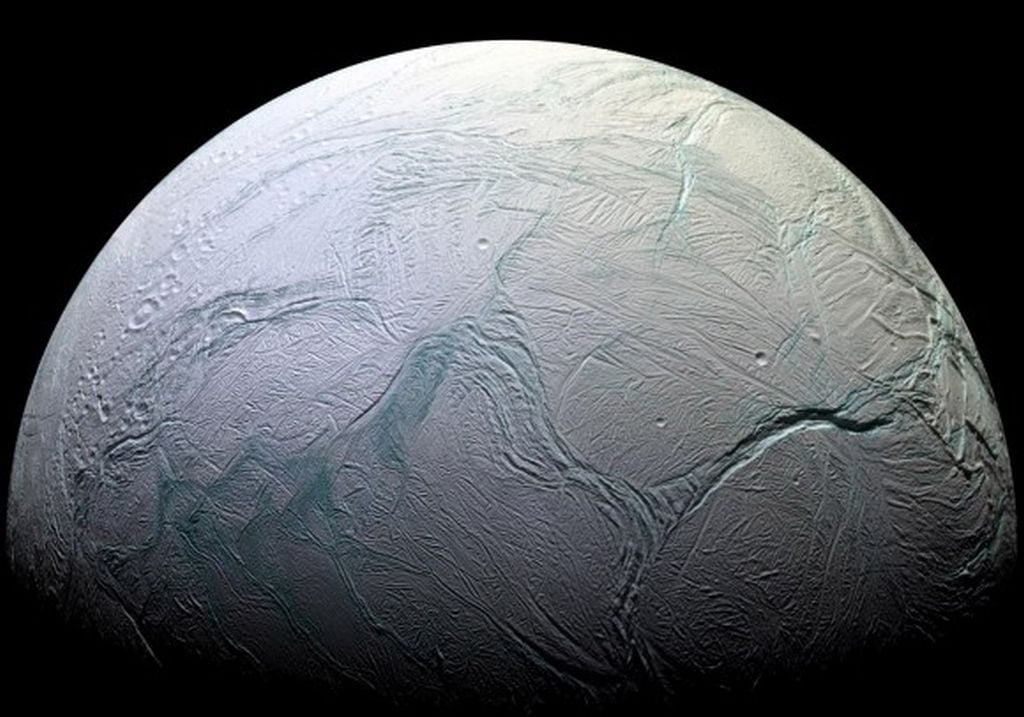

By all rights, the tiny world of Enceladus, the sixth-largest moon of Saturn, shouldn't be this interesting. It's no more than 1/7th the width of our own Moon and has a surface completely covered in water ice - nothing at all out of the ordinary. But in 2014 the NASA mission Cassini spotted something surprising: plumes of water spraying through cracks in the ice.

Further studies revealed that the icy crust of Enceladus hides an intriguing secret: a globe-spanning liquid water ocean. Indeed, the little moon might just have more liquid water than the Earth does.

But this ocean is almost entirely different than the ones we recognize on Earth. The oceans on our planet are relatively shallow - only a handful of kilometers deep. They don't even completely cover the planet. And they're heated from the top (via sunlight) with temperatures dropping the deeper you go.

The ocean of Enceladus is heated from below by the molten interior of the moon, and is likely more than 30 kilometers deep.

Salty Currents

But the two oceans may share something in common: massive currents that move huge volumes of water across long distances. On Earth, these currents are mostly driven by variations in temperature. Equatorial waters tend to be warmer than the poles due to the increased sunlight, and currents ensue to attempt to equalize those temperatures.

However, the currents on Enceladus would work differently, according to new research led by CalTech graduate student Ana Lobo. Observations with Cassini revealed that the icy shell is thinner at the poles and thicker at the equator. It's likely that the ice at the poles might be melting while the ice at the equator is freezing.

As the ice melts and freezes, it can change the local concentration of salt. For example, when salty water freezes, the salt gets left behind, causing any remaining water to become heavier. That heavy water sinks in that region, and rises where the ice is melting.

"Knowing the distribution of ice allows us to place constraints on circulation patterns," Lobo explains.

With a computer model in hand, Lobo and her colleagues discovered that Enceladus may host a large pole-to-equator system of ocean currents, which could carry potential nutrients for life.

According to co-author Andrew Thompson, "Understanding which regions of the subsurface ocean might be the most hospitable to life as we know it could one day inform efforts to search for signs of life."

Universe Today

Universe Today