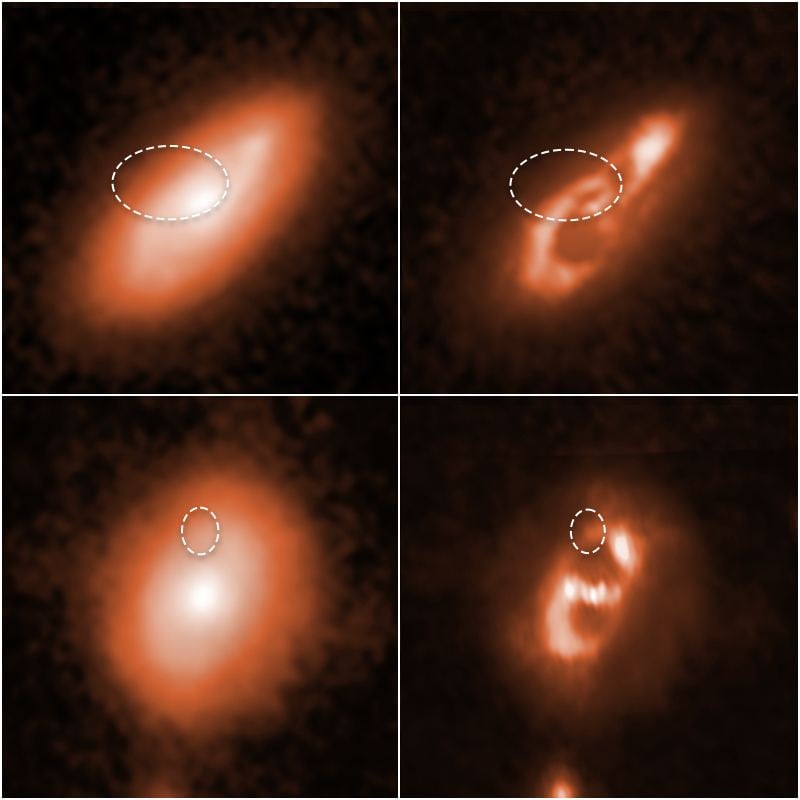

In a new survey, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope have managed to pinpoint the location of several Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs). FRBs are powerful jets of energy that, until recently, had mysterious, unknown origins. The research team, which includes University of California Santa Cruz' Alexandra Manning and Sunil Simha, as well as Northwestern University's Wen-fai Fong, performed a survey of eight FRBs, from which they were able to determine that five of them originated from a spiral arm in their host galaxies.

FRB sources are notoriously difficult to locate, because the bursts don't last very long, and few of them repeat, making follow-up observations incredibly challenging. The first FRB was seen in 2007 (though searching through archival data revealed that an FRB had been captured in July 2001 by the Parkes radio observatory in Australia). In the twenty years since, about a thousand of them have been detected - but only about 15 have had their source identified.

Based on the observations available so far, the best hypothesis for the origin of FRBs is that they are created by outbursts of energy from magnetars. Magnetars are a type of neutron star (incredibly dense stellar cores left over from the collapse of supergiant stars), and are named for their powerful magnetic fields. In 2020, one FRB was traced to a magnetar, lending the hypothesis some firm evidence that had previously been lacking.

This current research helps to further cement the magnetar hypothesis, ruling out some other possible FRB sources. For example, by identifying that FRBs seem to occur along galactic spiral arms, the research indicates that FRBs probably do not originate from the explosion of massive young stars, which cluster in brighter regions of the galaxies. It also rules out the merger of two neutron stars as an FRB source, because events like this tend to occur far from spiral arms, and in much older galaxies. Magnetars, in contrast, can exist quite easily within the galactic spiral arms that Hubble observed.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.The research also helped confirm the types of galaxies from which FRBs originate. Most large galaxies are accompanied by smaller dwarf galaxies (the Milky Way, for example, is surrounded by around 50 smaller galaxies, such as the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds, which are visible to the naked eye in the Southern Hemisphere). Previous attempts by ground-based telescopes to observe FRB sources were unable to resolve the images clearly enough to determine if the FRBs came from the main galaxy, or from a dwarf galaxy hidden behind it. The Hubble Space Telescope's advantage over ground-based telescopes comes from its ability to observe distant galaxies without any atmospheric distortions, enabling higher quality images. The Hubble survey concluded that the FRBs were indeed coming from the main galaxies, and that FRBs therefore tend to originate in young, massive, star-forming galaxies.

"Our results are new and exciting," explained lead author Alexandra Manning. "This is the first high-resolution view of a population of FRBs…Most of the galaxies are massive, relatively young, and still forming stars. The imaging allows us to get a better idea of the overall host-galaxy properties, such as its mass and star-formation rate, as well as probe what's happening right at the FRB position because Hubble has such great resolution."

The research will be published in an upcoming issue of *The Astrophysical Journal*.

Learn more:

" Hubble Tracks Down Fast Radio Bursts to Galaxies' Spiral Arms." NASA Goddard.

Universe Today

Universe Today