NASA’s planetary science program is making a big bet on Venus, after decades of putting its chips on Mars in the search for hints of past or present life out there in the solar system.

The bet comes in the form of a double dose of development funding for Discovery Program missions, amounting to as much as $1 billion. Both DAVINCI+ and VERITAS were selected from a field of four finalists in a competitive process — leaving behind missions aimed at studying Jupiter’s moon Io and Neptune’s moon Triton.

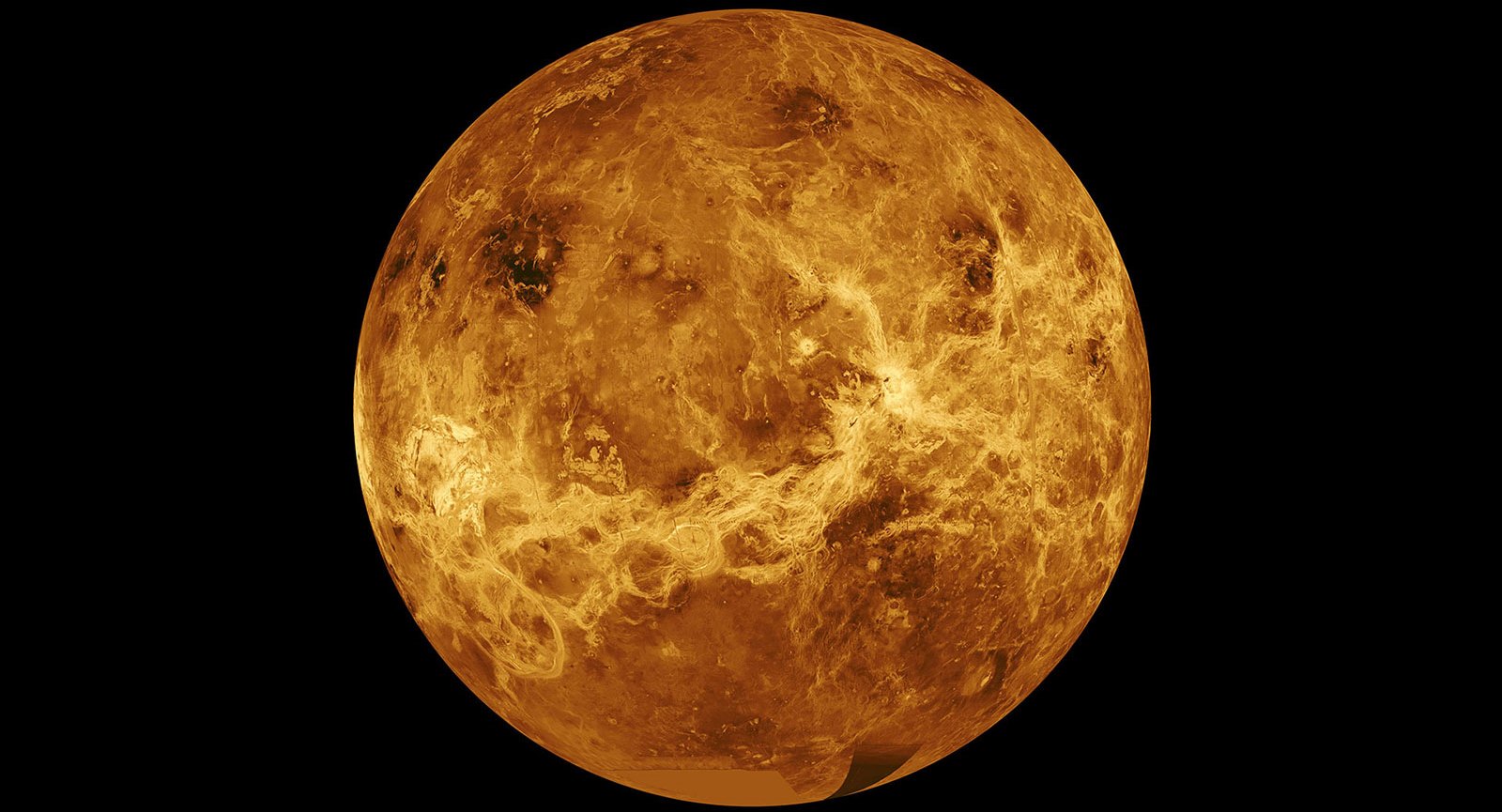

“These two sister missions are both aimed to understand how Venus became an inferno-like world capable of melting lead at the surface,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said June 2 in his first “State of NASA” address. “They will offer the entire science community the chance to investigate a planet we haven’t been to in more than 30 years.”

Lessons from Venus, which underwent a runaway greenhouse effect early in its existence, could improve scientists’ understanding of our own planet’s changing climate. The missions could also address one of the biggest questions about the second rock from the Sun: whether life could exist in the upper reaches of its cloud layer.

Last year, researchers reported seeing signs in Venus’ atmosphere hinting at the presence of a compound called phosphine, which could be associated with biological processes.

In the months since then, questions have been raised about how solid the evidence for life on Venus actually is. The two missions could provide data supporting the claims for biological activity. They could also tip the scales toward non-biological processes such as volcanism that can also produce phosphine.

Either way, the two new Discovery Program missions, scheduled for launch in the 2028-2030 time frame — will be a boon for a cadre of Venus-minded researchers who have long felt neglected.

“I’ve been pushing for this for literally my entire career,” David Grinspoon, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, enthused in a tweet. “So much to learn about climate, history of Earth-like worlds & life in the universe. I can’t describe how thrilled I am.”

Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at North Carolina State University, tweeted that NASA’s decision to double down on missions to Venus was “an INCREDIBLE outcome” and a big freakin’ deal (to put it in family-friendly terms).

According to a budget analysis by the Planetary Society, NASA spent $3.7 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars on its Venus missions through 2020, which pales in comparison with the $28.5 billion spent on Mars missions during the same period. Total planetary science spending amounted to $96.9 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars during that time.

Grinspoon noted that NASA’s Magellan orbiter, the last U.S. spacecraft to visit Venus, was launched in 1989 during his last year in graduate school. Since then, European and Japanese orbiters have send back additional information about Venus’ climate and atmosphere. NASA’s two new missions will build on that legacy and add a few new twists.

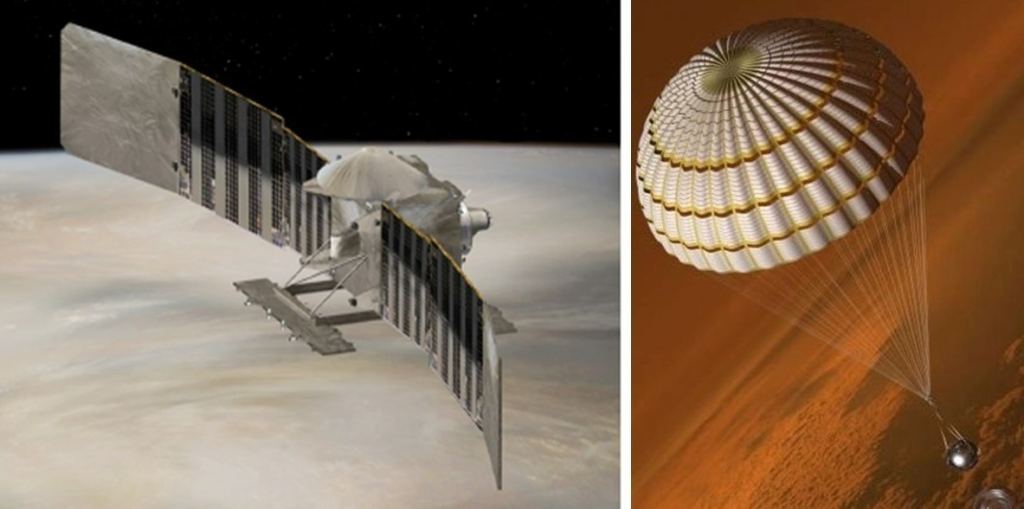

DAVINCI+, for example, is designed to send an spherical probe plunging through Venus’ atmosphere to collect chemical readings at different levels on the way down. The mission — whose acronym stands for “Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry and Imaging — could tell scientists whether Venus ever had an ocean.

Imagery from DAVINCI+ could provide high-resolution views of geological features known as “tesserae,” which NASA says may be comparable to Earth’s continents. Such features could shed light on Venus’ early geology and the effects of plate tectonics. Jim Garvin of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center is principal investigator.

VERITAS, which is an acronym for “Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography And Spectroscopy,” will use a synthetic aperture radar sensor to cut through Venus’ clouds and chart surface elevations in 3-D over nearly the entire planet. The readings could show whether processes such as plate tectonics and volcanism are still active.

The orbiter will also map infrared emissions from Venus — which could help scientists zero in on the planet’s surface composition and determine whether active volcanoes are releasing water vapor into the atmosphere. Suzanne Smrekar of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory is the mission’s principal investigator.

Contributors to VERITAS include the German Aerospace Center, the Italian Space Agency and France’s Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales. Lockheed Martin will build the spacecraft for DAVINCI+ and VERITAS.

NASA selected a pair of technology demonstrations to piggyback on the two selected missions, VERITAS will host the Deep Space Atomic Clock-2, a prototype for a new generation of ultra-precise clocks for space missions. DAVINCI+ will carry the Compact Ultraviolet to Visible Imaging Spectrometer, or CUVIS, which will make ultraviolet observations using a new technique. The readings could help scientists figure out why Venus’ clouds absorb so much ultraviolet light.

Still more missions to Venus are in the works, although it’s not yet clear whether or when they’ll get off the ground. Rocket Lab’s founder and CEO, Peter Beck, said last year that he’s “working very hard to put together a private mission to go to Venus in 2023.” Also last year, Breakthrough Initiatives announced that it’s funding a study to follow up on the questions surrounding the habitability of Venus’ clouds.

DAVINCI+ and VERITAS join a prestigious club of Discovery Program missions that includes Mars Pathfinder, the Messenger mission to Mercury, the Kepler space telescope and the Mars InSight lander. Two Discovery missions focusing on asteroids — dubbed Lucy and Psyche — are scheduled for launch in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

Each of the two newest Discovery Program missions will be awarded about $500 million for design and development, with launch vehicles yet to be selected.

Lead image: Venus’ surface features are revealed in an image based on data from NASA’s Magellan spacecraft and Pioneer Venus Orbiter. Source: NASA / JPL-Caltech