NASA's Juno mission is set for a close encounter with the Solar System's largest moon, Ganymede, on Monday. This will be the first flyby of the icy world since the Galileo and Cassini spacecraft jointly observed the moon in 2000. New Horizons also got a quick snap of Ganymede as it slingshotted around Jupiter on its way out to Pluto in 2007, but from a distance of 3.5 million kilometers away. Juno's pass on Monday will get much closer, approaching within 1038 kilometers of the surface.

This pass over Ganymede is the first in a series of flybys past Jupiter's Galilean moons, which will collectively be the highlight of Juno's extended mission. The probe's primary mission, which began in 2016, focused on the gas giant itself. Juno has been taking long, highly elliptical orbits around Jupiter, diving close in to collect data about the planet, before swinging way out again beyond the planet's harmful radiation, which threatens the spacecraft's hardware if it stays too long.

Juno will continue to study Jupiter during its extended mission, but its orbit will now swing it up over the poles, which had previously been hidden, and will also help put the planet in context. For example, Juno will carry out the first systematic examination of Jupiter's faint ring system, as well as visiting some of its moons.

The science goals for Monday's encounter with Ganymede are wide-ranging. Juno will, of course, take visible-light photos with JunoCam, which, besides being spectacular to look at, will allow planetary scientists to observe changes in Ganymede's surface over time: the photos can be compared to Galileo's from 20 years ago and Voyager's from 40 years ago.

Ganymede is the only moon with its own magnetosphere, so Juno's team is hoping to study it. Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Dustin Buccino explains that "As Juno passes behind Ganymede, radio signals will pass through Ganymede's ionosphere, causing small changes in the frequency that should be picked up by two antennas at the Deep Space Network's Canberra complex in Australia. If we can measure this change, we might be able to understand the connection between Ganymede's ionosphere, its intrinsic magnetic field, and Jupiter's magnetosphere."

Juno will also use its microwave radiometer to examine Ganymede's ice-crust, which will tell us more about its composition, temperature, and structure.

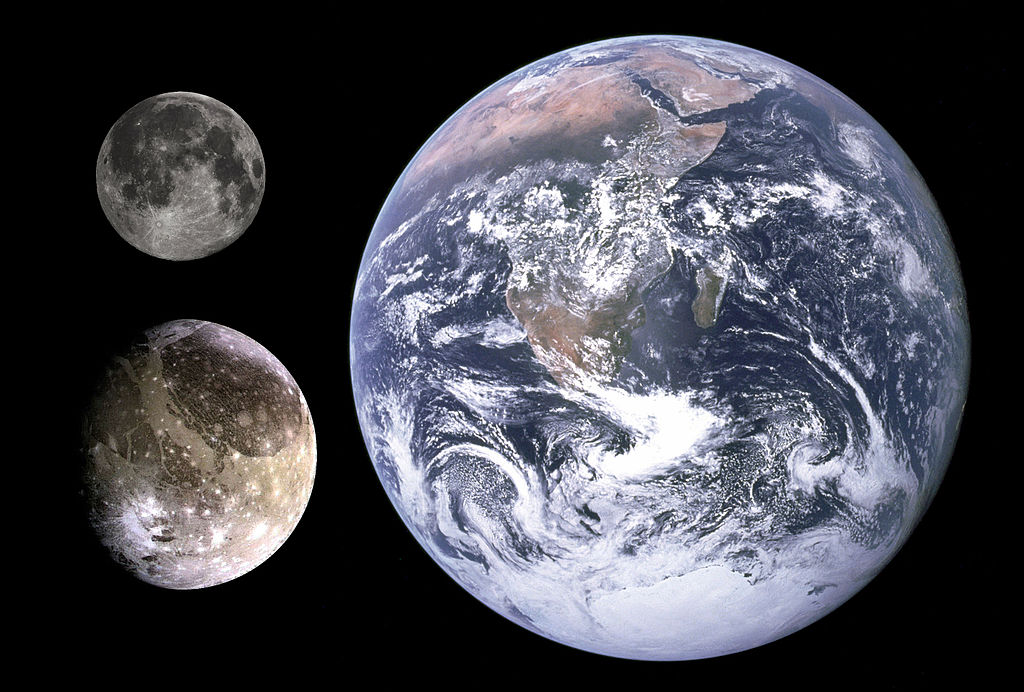

Ganymede is a fascinating world. Being larger than Mercury, it would be classified as a planet if it orbited the Sun instead of Jupiter. It's also intriguing because it's a water world, with liquid oceans beneath its surface. This makes it one of the best solar system candidates for microbial alien life. On the other hand, Ganymede's ocean might not have contact with rock at its bottom, instead being encased between two layers of ice sheets. On Earth, the chemical reactions caused by water contacting rock provide energy for some types of microbes - if Ganymede's ocean lacks this key ingredient, it may be sterile, but the jury is still out.

Liquid water-rock contact is expected to exist on another of Jupiter's moons, however: Europa. In the coming years, Juno will visit Europa too, more than once. Juno's extended mission will also give it a close-up look at Io, Jupiter's fiery innermost moon, a place more volcanically active than anywhere else in the Solar System. We can expect some stunning imagery, and new science, out of these upcoming flybys. Observations taken by Juno will complement and set the stage for two upcoming missions to Jupiter's moons. The European Space Agency's JUICE will launch in 2022, exploring Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa in more detail. NASA's Europa Clipper will follow later in the 2020s.

Learn more: " NASA’s Juno to Get a Close Look at Jupiter’s Moon Ganymede," JPL.

Featured Image: Mosaic and geologic map of Ganymede from Voyager and Galileo Data. Credit: USGS Astrogeology Science Center/Wheaton/NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Universe Today

Universe Today