The universe has some very extreme places in it – and there are few places more extreme than the surface of a neutron star. These ultradense objects form after a supergiant star collapses into a sphere about 10 kilometers (6 miles) in diameter. Their surface is extreme because of the gravity, which is about a billion times stronger than Earth. However, that gravity also forces the stellar remnant to be extraordinarily flat. Just how flat is the outcome of a new set of theoretical research by PhD student Fabian Gittins from the University of Southampton.

Previous estimates of the height of these “mountains” on the surfaces of neutron stars thought they might be able to grow up to a few centimeters. A combination of factors went into these estimates, including gravitational forces pulling any slight bump flat to the surface, as well as a pushing force from ultra-dense matter that might be capable of supporting the mountains themselves.

Credit – Kurzgesagt YouTube Channel

What the researchers found was that the forces at work on the surface were almost sure to limit the height of any such mountain to only a few fractions of a millimeter, decreasing the height of previous estimates by a factor of more than 100. It shows how close to a perfect sphere neutron stars really are.

Even those small imperfections on the surface of a neutron star can have large impacts on the wider universe. Some neutron stars spin, with the fastest (PSR J1748-2446ad) rotating at 716 times a second. With such high spin rates combined with such dense gravities, the small imperfections in the sphere represented by the “mountains” in the study should potentially result in gravitational waves.

So far scientists have been unable to find any gravitational waves emanating from a spinning neutron star. But that was not for want of trying – and they did find some ripples from a collision of two neutron stars. However, it seems that the current crop of gravitational wave detectors, which made headlines just a few years ago for the first ever detection of any type of gravitational wave, are simply not sensitive enough to pick up the slightly smaller waves theory predicts will come from a neutron star.

Luckily though, new detectors are on the horizon, such as the Einstein Telescope and the Cosmic Explorer. With much more sensitive instruments, we might just be able to detect the large gravitational fluctuations that even these tiny, sub-millimeter heights, are capable of throwing out into the universe.

Learn More:

RAS – A bug’s life: millimetre-tall mountains on neutron stars

LiveScience –

Learn More:

RAS – A bug’s life: millimetre-tall mountains on neutron stars

LiveScience – Neutron star ‘mountains’ may be blocking our view of mysterious gravitational waves

LIGO – How High Are Pulsar “Mountains”?

Gizmodo – Neutron Stars Have Mountains That Are Less Than a Millimeter Tall

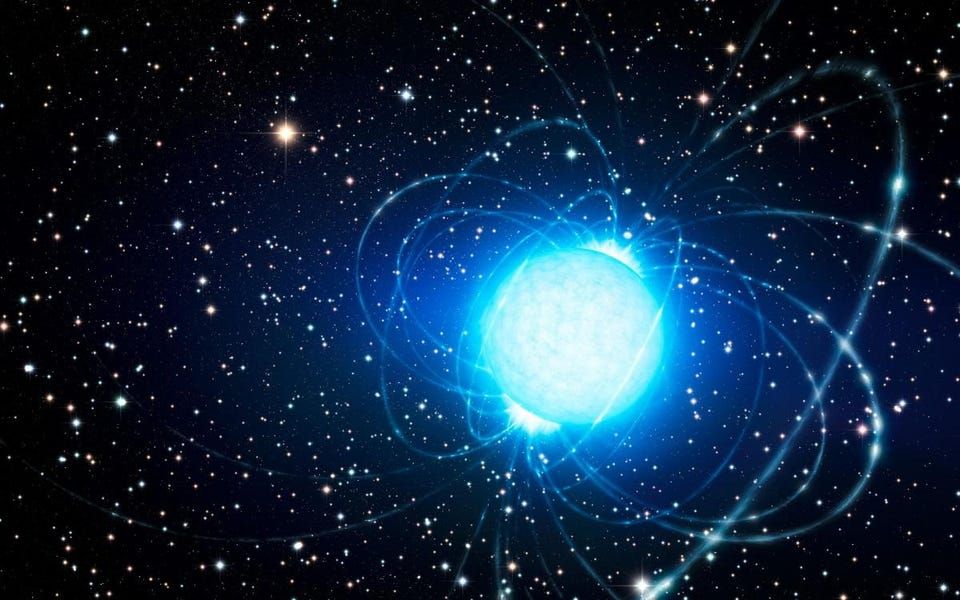

Lead Image:

Artist’s depiction of a neutron star.

Credit – ESO / L. Calçada

Stars don’t have mountains.