So much in the astronomy community revolves around the decadal survey. Teams of dozens of scientists put hundreds of hours developing proposals that eventually try to impact the recommendations of the survey panel that influence billions of dollars in research funding over the following decade. And right now is the prime time to get those proposals in. One of the most ambitious is sponsored by a team led by researchers at John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). Their suggestion – it’s time to land on Mercury.

This isn’t the first time the idea has been aired, but new technologies make this incarnation feasible for the next decade. The current proposal was first floated by APL scientists to NASA, which funded a mission concept study that produced an in-depth 82-page review of a mission outline that is available from NASA.

There are five main mission objectives:

Any lander will face a daunting challenge in landing. Currently, the best images we have of the innermost planet were captured by NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft, which orbited Mercury from 2011–2015. But these images cover only minimal parts of the surface, and their resolution is not ideal for selecting a specific landing site. Each pixel in the highest-resolution images MESSENGER returned covered at best 2–3 m of the planet’s surface at best.

That resolution is not good enough when a 3-meter boulder could completely topple the lander on its descent. BepiColombo, an ESA/JAXA mission currently on its way to Mercury, should be able to capture some higher resolution images that could aid in landing. However, the process will still most likely be reliant on an autonomous landing protocol.

Assuming the lander does touch down, it will have to get to work quickly. The mission would only be designed to last during Mercury’s night, which is 88 Earth days long. Trying to design a lander to withstand the sun’s full force during Mercury’s daytime would require too much of the instruments the lander hopes to carry. In its current iteration, the mission would plan to touch down during the planet’s dusk and then operate continuously for about three months before dawn brings the mission to a close.

A lot of science can get done in those months, though. During dusk, the lander will take some panoramic shots of its surroundings to provide some context to the smallest rocky planet for the first time. It will also be equipped with lights that will allow it to illuminate its nearby surroundings even in the pitch black of Mercury’s night.

That light and all the instruments on board will be powered by a radioisotope thermal generator, a common power supply for space-faring landers and rovers. Its adoption showcases another important aspect of the lander’s mission design – it will leverage technologies that have already been developed.

The techniques needed to achieve the mission’s science goals are similar to those already used on other planets. Many of the technologies, such as magnetometers and spectrometers, can be repurposed from designs used on other missions. This would lower the mission’s overall cost, which wouldn’t have to do the development work for its scientific instrumentation from scratch.

That scientific instrumentation would still be quite impressive. The suggested suite of instruments includes several spectrometers, cameras, and magnetic sensors, all of which should be able to operate through Mercury’s night. But the mission designers stress that the exact payload is still flexible, with the expectation that any future mission planning will adapt other technologies for use as necessary.

Dr. Carolyn Ernst, the PI of the mission concept, is excited about what those proven instruments will discover. “Mercury is the only rocky planet we haven’t landed on – we’ve never seen the surface up close. We need landed measurements to better understand Mercury and to put our own Earth into context,” she says.

But comparing Mercury to Earth isn’t the only reason to go. Dr. Nancy Chabot, the deputy PI of the mission concept, points out that the data collected about Mercury so far are both limited and difficult to interpret. To put it in her words, “It’s exciting to fill in this black box,” where the “black box” refers to a figure in the report that shows an image from the surface of each of the rocky worlds in the inner solar system, but Mercury is shown just as a black box as there is no such view – yet.

Drs. Ernst and Chabot and their colleagues have been puzzling over the mysteries surrounding Mercury for years, as they were instrumental in helping to plan and analyze data from the MESSENGER mission. But they think of that successful mission as only a first step toward truly understanding this unique planet.

There’s still a lot more to be done before any lander will help contribute to that understanding. The final report from the Decadal survey, which could suggest prioritizing the mission, is slightly less than a year away. The APL team is busy fleshing out mission plans and ideas to help make the idea of a Mercury lander as appealing as possible. Even so, Mercury researchers will hopefully have more to cheer about as BepiColombo gets close to its arrival at the innermost planet in 2025. That mission’s success might drive more interest in Mercury itself – potentially culminating in a lander that provides plenty of data, and finally, some pictures from the surface to fill in Mercury’s blank space in our solar system’s scrapbook.

Learn More:

APL – Mercury Lander

Space.com – What Would It Take to Land on Mercury? It’s Time to Find Out, Scientists Say

NASA – Mercury Lander Mission Concept Study

UT – Missions to Mercury

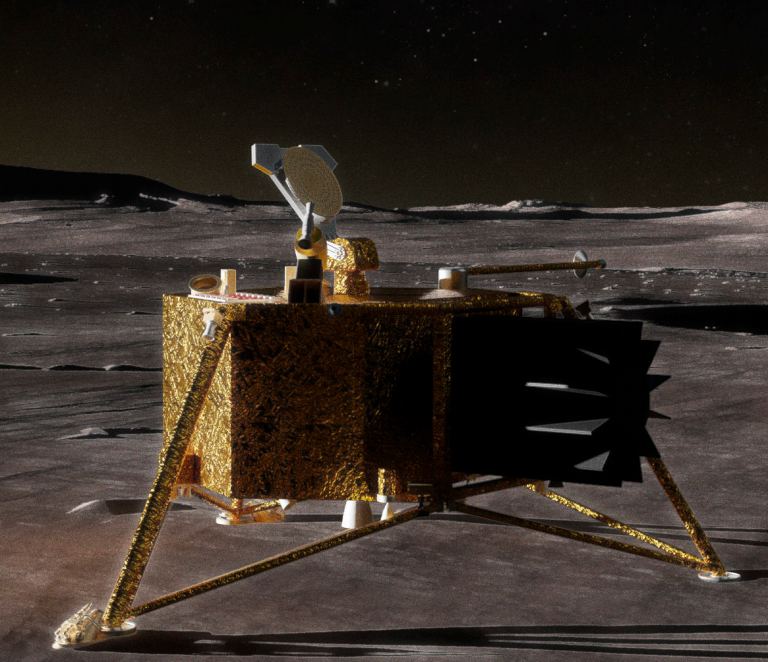

Lead Image:

Artist’s concept of a Lander on Mercury.

Credit – JHU-APL

Every Martian year (which last 686.98 Earth days), the Red Planet experiences regional dust storms…

If Intermediate-Mass Black Holes (IMBHs) are real, astronomers expect to find them in dwarf galaxies…

There are plenty of types of stars out there, but one stands out for being…

As far as we can tell, life needs water. Cells can't perform their functions without…

Dubbed CADRE, a trio of lunar rovers are set to demonstrate an autonomous exploration capability…

Astronomers have identified sulfur as a potentially crucial indicator in narrowing the search for life…