Remember when engineers proposed one-way trips to Mars, because round trips are just too expensive to bring people back to Earth again?

Getting people home from Mars can only happen in two ways. One is to lug all the return fuel with you when you launch from Earth, which is prohibitively difficult and expensive. The second way is to make the return fuel in-situ from Martian resources. But how?

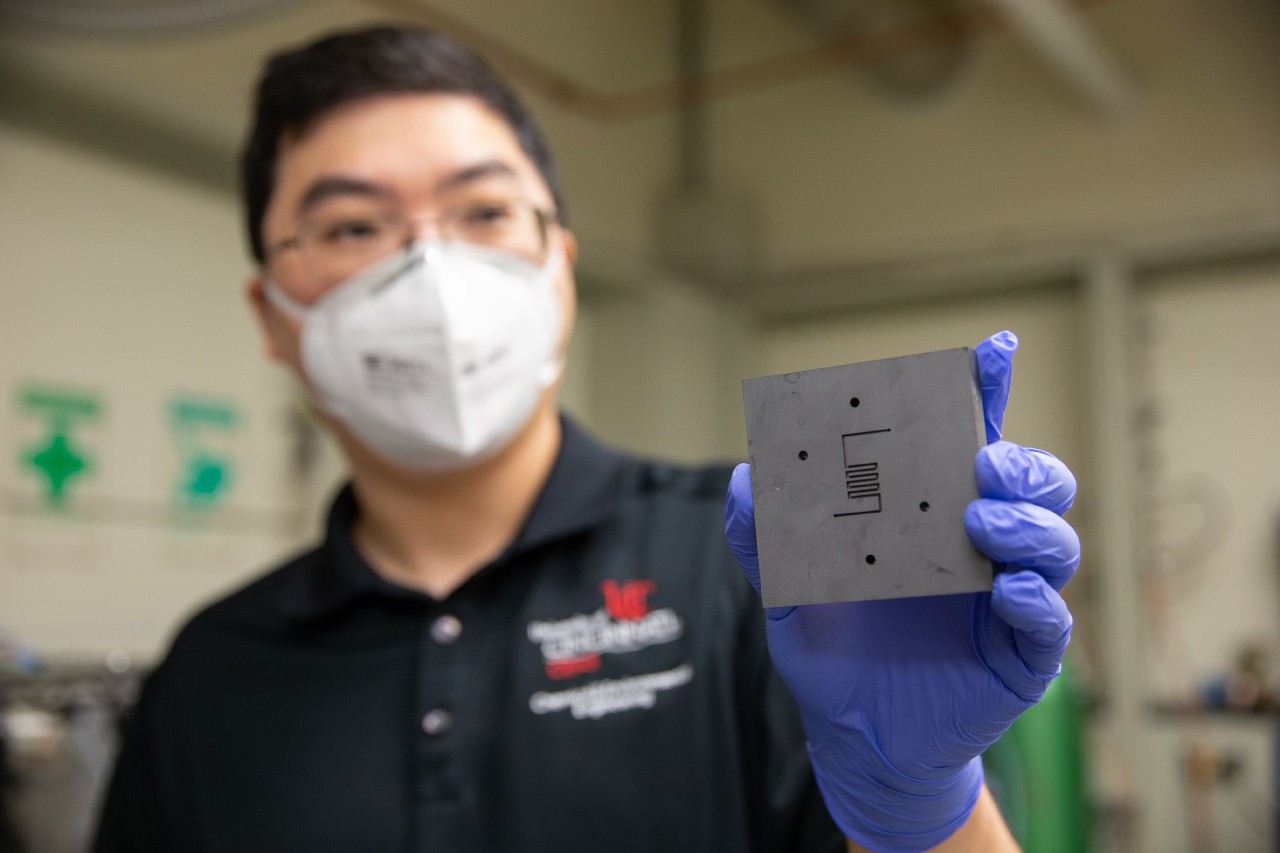

A group of researchers from the University of Cincinnati propose using a type of reactor that was used from 2010-2017 aboard the International Space Station, which scrubbed the carbon dioxide from air the astronauts breathe and generated water to drink, with methane as a biproduct. On Mars, this reactor, called a Sabatier reactor, could take carbon dioxide from Mars’ atmosphere and create methane for fuel.

“Right now if you want to come back from Mars, you would need to bring twice as much fuel, which is very heavy,” said professor Jingjie Wu, who is leading a group of students in this research. “And in the future, you’ll need other fuels. So we can produce methanol from carbon dioxide and use them to produce other downstream materials. Then maybe one day we could live on Mars.”

There’s another benefit to this research: it could also be used to convert greenhouse gases to fuel here on Earth, which could help address climate change.

Wu and his students, including lead author of a new paper and UC doctoral candidate Tianyu Zhang, are experimenting with different carbon catalysts in the the Sabatier reactor, which was named for the late French chemist Paul Sabatier. The Sabatier reactor was installed on the ISS in 2010 and was used until 2017. Contrary to some news reports regarding the research by Wu, Zhang and colleagues, the ISS system was never used to create fuel for orbital boosts.

“On the station, the water is recovered for use in the life support system,” explained Leah Cheshier, communications specialist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. “The methane is vented to space given the station does not have a way to use it. The space station has not used this methane for orbital reboosts.”

The scientists outlined their research, published in Nature Communications, as they reviewed different catalysts to create different biproducts, such as methane and ethylene. They have had success using graphene quantum dots — layers of carbon just nanometers big — that can increase the yield of methane.

“In the future we’ll develop other catalysts that can produce more products,” said Zhang, in a press release.

The team said the process is scalable for use in power plants that can generate tons of carbon dioxide. And it’s efficient since the conversion can take place right where excess carbon dioxide is produced, both on Earth and at Mars, where the atmosphere is composed almost entirely of carbon dioxide. Fuel could be created and stored for the return trip home, as well as for fuel to run generators or other life support systems on Mars.

“It’s like a gas station on Mars. You could easily pump carbon dioxide through this reactor and produce methane for a rocket,” Wu said.

The researchers said a lot of progress in Sabatier reactors have been made in recent years, and it could be very important for green energy for Earth.

“The process is 100 times more productive than it was just 10 years ago. So you can imagine that progress will come faster and faster,” Wu said. “In the next 10 years, we’ll have a lot of startup companies to commercialize this technique.”

The Sabatier system on the space station was returned to ground in 2017 for assessment of its condition following its years of operation, NASA’s Cheshier told Universe Today. NASA has recently initiated an effort to perform design upgrades to Sabatier to improve performance and maintainability. An upgraded unit is planned to be launched to the space station in approximately 2025.

Lead image caption: UC chemical engineer Jingjie Wu holds up the reactor where a catalyst converts carbon dioxide into methane. UC’s research makes him optimistic that scientists will be able to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand