According to the most widely accepted theories, the Moon formed about 4.5 billion years ago after a Mars-sized object (Theia) collided with Earth. After the resulting debris accreted to create the Earth-Moon system, the Moon spent many eons cooling down. This meant that a few billion years ago, lakes of lava were flowing across the surface of the Moon, which eventually hardened to form the vast dark patches (lunar maria) that are still there today.

Thanks to the samples of lunar rock brought back to Earth by China's *Chang'e 5* mission, scientists are learning more about how the Moon formed and evolved. According to a recent study led by the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences (CGAS), an international team examined these samples to investigate when volcanism on the Moon ended. Their results are not only filling in the gaps of the Moon's geological history but also of other bodies in the Solar System.

The study, which recently appeared in the journal Science, was led by Xiaochao Che of the Beijing Sensitive High-Resolution Ion Micro Probe Center, located at the CGAS Institute of Geography. He was joined by researchers from the Planetary Science Institute (PSI), McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Shandong Institute of Geological Sciences, and several universities from the US, UK, and Australia.

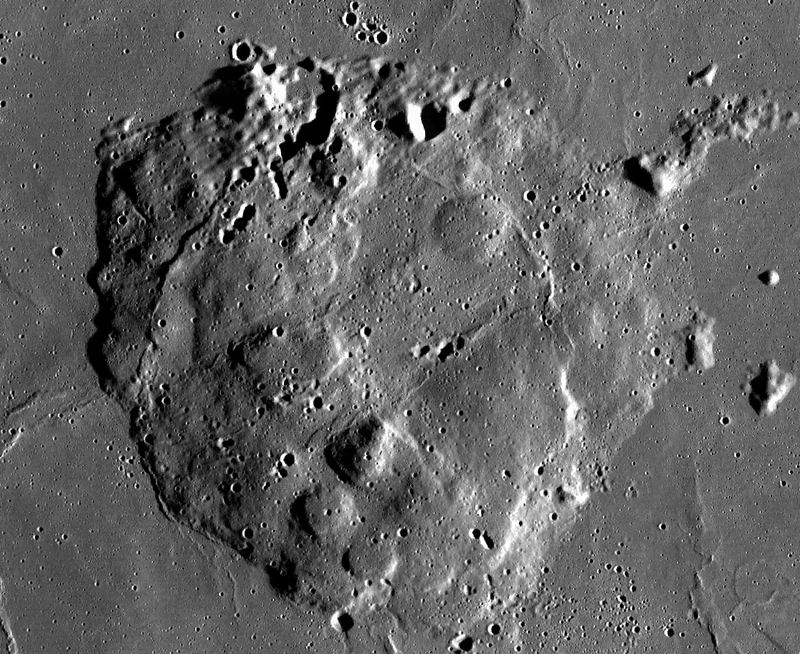

The samples obtained by the Chang'e-5 rover are the first to be returned to Earth since the Apollo era (45 years ago) and were obtained from the volcanic plain known as Oceanus Procellarum (Latin for "Ocean of Storms"). This lunar region is unique among lunar terrae, as it is believed to have hosted the most recent basalt lava flows on the Moon. Jim Head, a research professor in Brown's Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, was a co-author on the new study.

The Chang'e-5 spacecraft landed in this region on Dec. 1st, 2020, and managed to collect about 1,730 g (61.1 oz) of lunar rock from this region, including a core sample obtained from a depth of ~1 m (3.3 ft) beneath the surface. As he explained in a recent *News from Brown* press release:

"These samples come from a region of the Moon that’s been largely unexplored by landed spacecraft. Previous samples from the Apollo missions and the Soviet Luna missions all come from the central and eastern part of the Moon’s near side. " But it became clear as we collected more remote sensing data that the most recent volcanism on the Moon was absolutely in that western portion, so that region became a prime target for sample collection. Specifically, the samples came from near Mons Rümker, a volcanic mound in the largest of the lunar maria, Oceanus Procellarum."

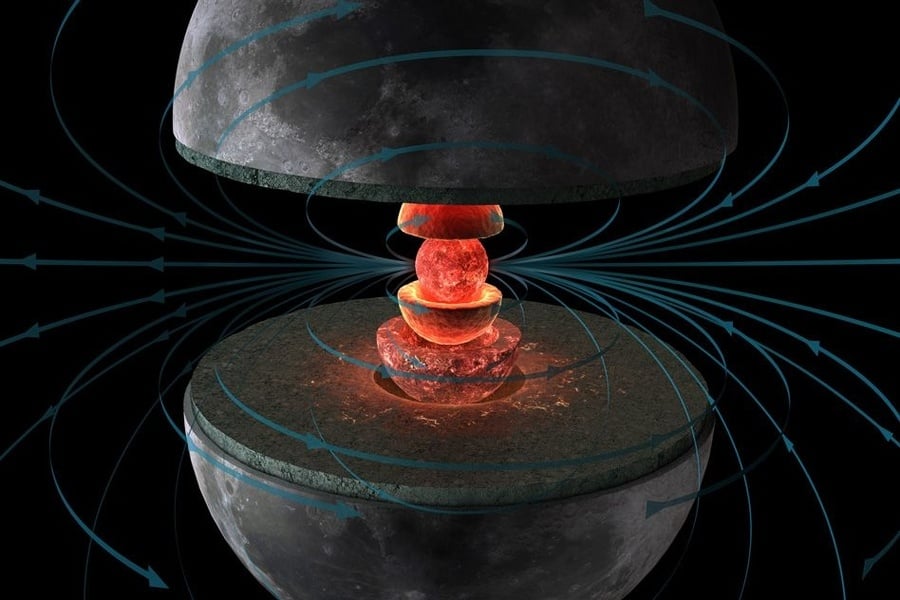

The Oceanus Procellarum region is characterized by high concentrations of radioactive elements such as potassium, uranium, and particularly thorium. These generate heat through long-lived radioactive decay and are believed to have played a role in prolonging magmatic activity on the near side of the Moon. After examining the samples through radiometric dating, the team concluded that they were (on average) 2 billion years old.

"However, in these samples, we didn't actually see an elevated radioactive element composition," said Head. "If these radioactive elements are driving the volcanism in this region, we expect to see enhanced radioactivity in the samples. But we didn't. Instead, the composition was similar to mare basalts from older deposits. So that casts some doubt on that hypothesis for long-lasting volcanism."

Essentially, their examination revealed that alternative explanations are needed for why the Oceanus Procellarum region experienced a prolonged period of lunar magmatism. However, the most significant takeaway from this study is how it managed to constrain the age of some of the most recent basaltic lava samples from the Moon. This not only establishes an endpoint for the Moon's most active volcanic period but is critical to modeling its thermal evolution and geological history as well.

And as Head indicated, it also serves as a means for calibrating the timing of other events in the Moon's geological history and on other bodies in the Solar System:

"When we look at a surface or a feature on the Moon from which we don’t have samples for radiometric dating, we try to estimate its age through the size-frequency distribution of impact craters. Basically, as time goes by, larger impacts become more rare. So by counting craters of different sizes, we can establish a relative age of a surface.

Last but not least, these examinations allow scientists to fill critical gaps in our understanding of the Moon's history. "But between about one billion and three billion years ago, we don't have many good data points to tell us what the impact flux looks like," Head added. "So having an absolute radiometric date for this surface helps us to calibrate the flux curve, which helps us to date other surfaces. And that's not true only for the Moon. This helps us calibrate ages for Mars, Venus, and elsewhere."

The samples obtained by the Chang'e-5 rover are also the first to be returned to Earth since the Apollo era (45 years ago). You might say that the results of this research are a preview of how our renewed lunar exploration efforts will yield new and valuable insights into how the Earth-Moon system formed and evolved. These, in turn, could shed light on how habitable conditions emerged and lasted on Earth but no other bodies in the Solar System.

Further Reading: Brown University *, Science*

Universe Today

Universe Today