NASA has pushed back the timetable for landing astronauts on the moon for the first time in more than a half-century from 2024 to no earlier than 2025.

Blue Origin's unsuccessful legal challenge to a $2.9 billion lunar lander contract awarded to SpaceX was one of the factors behind the delay in the Artemis moon program, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said during a Nov. 9 teleconference.

Nelson also pointed to Congress' previous decisions not to fund the lander program as fully as NASA wanted, plus delays forced by the COVID-19 pandemic and the fact that "the Trump administration target of a 2024 human landing was not grounded in technical feasibility."

"After having taken a good look under the hood these past six months, it's clear to me that the agency will need to make serious changes for the long-term success of the program," he told reporters.

One big change is that the estimated cost of developing NASA's Orion deep-space capsule during the period between 2012 and the first crewed test mission has risen from $6.7 billion to $9.3 billion.

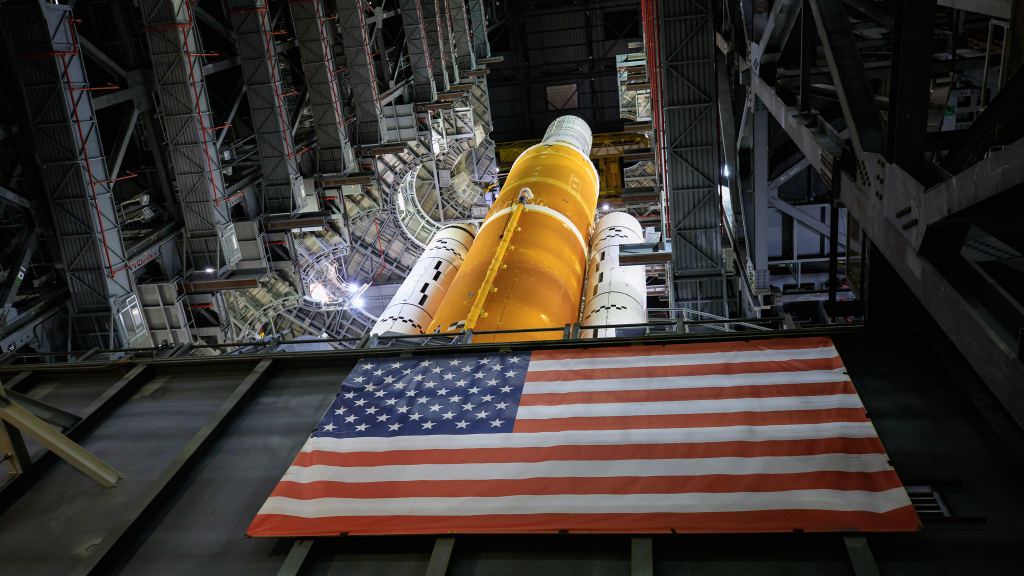

The estimated development cost for NASA's heavy-lift moon rocket, known as the Space Launch System or SLS, adds up to another $11 billion, said Jim Free, NASA's associate administrator for exploration systems development.

NASA is currently gearing up for the first SLS test launch as early as next February, with the objective of sending an uncrewed Orion capsule beyond the orbit of the moon and back over the course of a mission lasting more than three weeks.

That mission, known as Artemis 1, would be followed by the crewed Artemis 2 mission, coming no earlier than May 2024. Artemis 2 would follow a similar beyond-the-moon trajectory, and rehearse proximity operations for the crewed lunar landing to follow during Artemis 3.

The likeliest timeline calls for yet another SLS to launch an Orion capsule carrying Artemis 3's astronauts in 2025, Nelson said. Once the Orion craft reaches lunar orbit, the crew would transfer to SpaceX's Starship craft for the Artemis program's first moon landing.

Nelson noted that Chinese space officials are talking about sending their astronauts, or taikonauts, to the moon's south pole during the 2020s. He said he'd rather see Americans become the first humans to return to the lunar surface after the last Apollo moon landing in 1972.

"It's the position of NASA, and I believe the United States government, that we want to be there first, back on the moon after over half a century," Nelson said.

He also stressed the importance of crewed lunar operations as a prelude to Mars exploration. "We've got a lot of stuff to do on the moon, including building habitats and learning how we're going to exist for long periods of time in that environment, in order to prepare us to take astronauts to Mars," Nelson said.

While the challenges to SpaceX's Starship contract were being considered, NASA was barred from working with SpaceX on adapting Starship for lunar landings — and from paying SpaceX to work on Starship. SpaceX has nevertheless continued to build and test Starship components at its Starbase facility on the South Texas coast, in part because the company has other applications in mind, ranging from orbital satellite deployment to its own trips to Mars.

SpaceX plans to use Starship to conduct an uncrewed demonstration mission to the lunar surface sometime before Artemis 3. Lots of details remain to be worked out, however. Nelson said NASA's contacts with SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell and other company representatives resumed right after last week's ruling on Blue Origin's challenge and will ramp up over the weeks ahead.

Partly in response to concerns that were raised during the legal challenge, NASA has already begun a follow-up program to support the development of multiple commercial landing systems capable of getting astronauts to the moon.

Five of the companies that were involved in the "Option A" competition to build the Artemis program's first lunar lander — SpaceX, Blue Origin, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Dynetics — are receiving a total of $146 million from NASA to continue working on crew-capable landing systems. NASA will address future phases of the lunar lander program in solicitations due for release next year.

Nelson stressed that Congress would need to provide full funding for the lander development program, which he said would produce roughly one lander per year over a 10-year period. "That number is $5.7 billion over about six years," he said.

NASA is also planning to streamline how it awards contracts for SLS rockets. Right now, a variety of companies build SLS components. For example, Boeing is the prime contractor for the core stage, United Launch Alliance built the initial version of the SLS' upper stage, and Northrop Grumman is responsible for the solid rocket boosters.

"We're going to consolidate multiple SLS contracts into a single production operations contract, as well as consulting with industry on the feasibility of having a long-term service provider for the rocket," Nelson said.

For now, NASA is sticking to a mission architecture that calls for launching its astronauts from Florida with SLS and Orion, and then transferring them to a commercial landing system only for the trip from lunar orbit to the lunar surface and back. But Nelson suggested that plan could be reconsidered once SpaceX proves that Starship and its Super Heavy booster can handle lunar missions from start to finish.

"We're going with what we got, and if anybody comes up with another alternative, we're glad to look at any other alternative," he said.

Lead image: An artist's conception shows SpaceX's Starship on the lunar surface. Credit: SpaceX via NASA.

Universe Today

Universe Today