Earlier this month, the Russian military conducted an anti-satellite (ASAT) missile test, launching a PL19 Nudol interceptor missile at a now-defunct Soviet-era intelligence satellite, KOSMOS 1408. The impact obliterated the spacecraft, creating a debris field consisting of approximately 1500 pieces of trackable debris, and potentially hundreds of thousands of pieces that are too small to monitor with ground-based radar. In the aftermath of the test, the debris field crossed the orbit of the International Space Station (ISS) repeatedly, causing the crew to take emergency precautions and shelter in their descent capsules, ready for a quick return to Earth in the event that the station was hit.

While the station and its crew escaped without harm this time around, the November 15 test demonstrated far too clearly that ASATs pose a real danger to human life. They can also wreak havoc on the rest of Earth's space infrastructure, like communications satellites and other orbital systems. Debris from an ASAT test remains in orbit long after the initial incident is over (the higher the orbit, the longer lasting the debris), and if humanity's space infrastructure is to be sustainable, the era of ASATs must come to an end, and soon.

Russia's November 15 test was a particularly egregious incident, sending debris into the path of Russia's own cosmonauts living aboard the ISS. But if we're honest, there's plenty of blame to throw around when it comes to ASAT tests. Few launch-capable countries have abstained from conducting their own. In 2007, China blew up one of its satellites, creating 40,000 new pieces of debris in a high enough orbit that much of it remains, and will remain, for decades to come. A year later, the United States shot down its own malfunctioning spy satellite, claiming the toxic hydrazine-filled machine posed a threat to human health if it crashed down to Earth in one piece. It was a weak excuse – space debris falls back to Earth all the time and rarely causes an incident – but at least the American test was at a lower altitude than the Chinese test, meaning the debris deorbited more quickly. More recently, India conducted an ASAT test in 2019, also at a relatively low altitude. But even these low altitude tests are not without risk, as the impact can boost debris into higher, longer-lasting orbits. The bottom line is that there's no such thing as a responsible ASAT test, yet they keep happening.

Perhaps we shouldn't be surprised. In the history of space exploration, there's no shortage of nations using spaceflight to show off their military prowess, a legacy of Cold War politics that just won't go away. But going forward, these irresponsible displays have no place in a sustainable space environment, and the consequences will only get worse as low Earth orbit becomes a busier place. Planned Mega-constellations promise to increase the number of active satellites by an order of magnitude in the coming decades. It's already begun, with Elon Musk's Starlink constellation rapidly expanding to nearly 1700 units this year.

This growing population of spacecraft has experts worried that future ASAT tests might be more catastrophic. A new paper by UBC researchers Sarah Thiele and Aaron Boley was released on ArXiv this week, modeling what an ASAT test like the 2019 Indian test might look like in a busier space environment. What if, they ask, there were 65,000 active satellites in orbit – as opposed to the current ~7000 – a number that may not be too unrealistic in the near future. In this high-density scenario, their result indicated a 30% chance of a collision for every test conducted (for fragments of 1cm or larger), and an impact of debris smaller than 3mm would be almost guaranteed. Long story short, the busier space gets, the less room there is to blow things up consequence-free.

This video contains audio from the moment Mission Control informed astronauts on the ISS about the risk of debris from the Kosmos-1408 ASAT test. The crew subsequently carried out emergency procedures and took shelter. Time stamps for key moments during the critical first three hours are available in the video's description. Credit: NASA, via Space SPAN.Public opinion is certainly turning against ASAT test perpetrators, with rapid, widespread condemnation following the most recent tests by India and Russia. But something more substantial may be necessary to reign in the worst offenders. International norms, treaties promising good behaviour in space, and United Nations resolutions could all use an update, and the major spacefaring nations will need to take the lead if there is to be any hope of success.

There are already plenty of challenges to overcome in space in the next decade, like how to deal with radiation in long-term human spaceflight, or how to manage mega-constellations without impeding ground-based astronomy. Adding to the list of challenges by conducting unnecessary, irresponsible ASAT tests is absurdly short-sighted in today's space environment. It's about time they stop. Period.

Learn more: Sarah Thiele and Aaron Boley, " Investigating the risks of debris-generating ASAT tests in the presence of megaconstellations, " ArXiv.

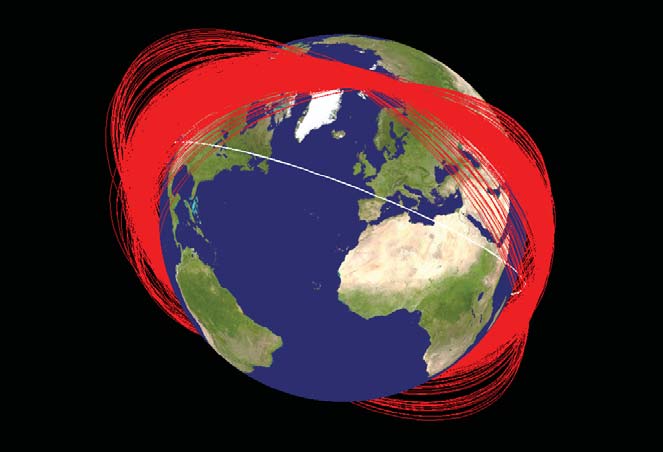

Featured image: A model of the orbital debris environment. Credit: ESA.

Universe Today

Universe Today