The study of extrasolar planets has revealed some interesting things in recent decades. Not only have astronomers discovered entirely new types of planets – Super Jupiters, Hot Jupiters, Super-Earths, Mini-Neptunes, etc. – it has also revealed new things about solar system architecture and planetary dynamics. For example, astronomers have seen multiple systems of planets where the orbits of the planets did not conform to our Solar System.

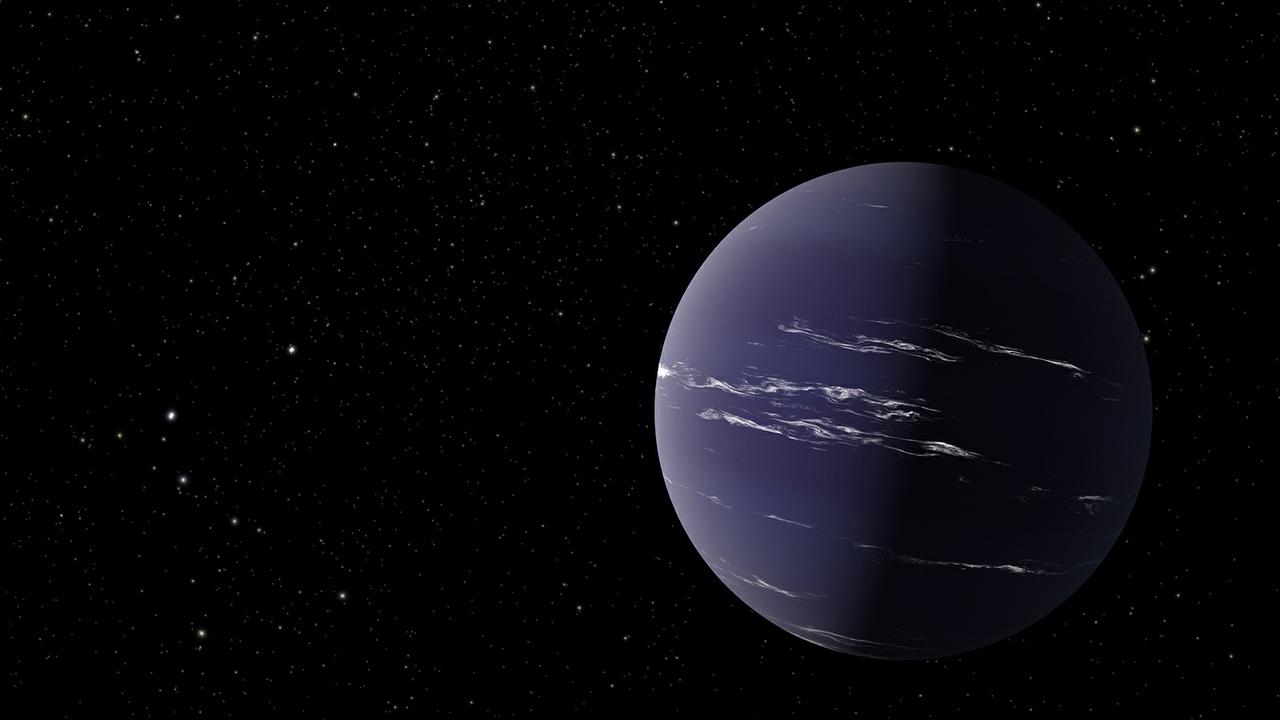

According to a new study led by the University of Bern, an international team of researchers recently observed a Mini-Neptune (TOI-2257 b) orbiting a red dwarf star located about 188.5 light-years from Earth. What was interesting about this find was how the small ice giant had such an eccentric orbit, which is almost twice as long as it is wide! This is almost two and a half times as eccentric as Mercury, making TOI-2257 b the most eccentric planet ever discovered!

The study was the work of the SAINT-EX consortium, made up of researchers from the Center for Space and Habitability (CSH) at the University of Bern and the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS (jointly-run by the University of Bern and Geneva). They were joined by members from the ESA’s European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the NASA Ames Research Center, and multiple universities and research institutes.

For the sake of their study, the team relied on data obtained by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which observed the red dwarf star TOI-2257 for four months and noticed repeated dips in luminosity. This is known as the Transit Method (Transit Photometry), where periodic dips in brightness are considered to be possible indications of a planet passing in front of the star (aka. transiting) relative to the observer.

However, the gaps between observations during those four months created a measure of uncertainty. While the dips indicated the presence of an exoplanet measuring 2.2 Earth radii, it was unclear if the planet had an orbital period of 176, 88, 59, 44, or 35 days. Hence, the team combined the TESS data with observations from the Search And characterIsatioN of Transiting EXoplanets (SAINT-X), the TRAPPIST-North, and the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory (FLWO) telescopes.

The SAINT-EX telescope was particularly helpful in confirming the planet’s orbital period. After witnessing a partial transit at 35 days, it picked up many more transits, each with a period of 35 days. “Another 35 days later, SAINT-EX was able to observe the entire transit, which gave us even more information about the properties of the system,” said CSH researcher Robert Wells, a co-author on the study who was involved in the data processing.

This 35-day period indicates that TOI-2257 b orbits within its parent star’s circumsolar habitable zone (HZ), the distance where liquid water can exist on its surface. The shorter orbital period also makes it easier to study this planet since scientists will be able to observe transits regularly, thereby increasing opportunities to measure light from the parent star as it passes through the planet’s atmosphere. This produces spectra, which astronomers can use to determine the chemical composition of the atmosphere and look for biosignatures.

Another facilitating factor about TOI-2257 b’s orbit is its eccentricity, which allows for slow transits in front of its star. Nicole Schanche, a researcher with the CSH and the NCCR who led the study, explained in a recent University of Bern press release:

“We found that TOI-2257 b does not have a circular, concentric orbit. In terms of potential habitability, this is bad news. While the planet’s average temperature is comfortable, it varies from -80°C to about 100°C depending on where in its orbit the planet is, far from or close to the star.”

In our Solar System, Mercury has the most eccentric orbit of any planet, with a rating of 0.205. If you were to plot Mercury’s orbit on a two-dimensional plane, one dimension would be 20% longer than the other. While Pluto’s eccentricity is greater (0.2488), the tyranny of naming conventions prevents us from saying it holds the record (for now!) But with an eccentricity of 0.50, TOI 2257 b’s orbit is 50% longer along one axis, which happens to be the one facing toward us!

According to Schanche and her colleagues, a possible explanation is that there’s another giant planet lurking in the outer system that is disturbing the orbit of TOI 2257 b. Further observations will be needed using the Radial Velocity Method (aka. Doppler Spectroscopy) to determine if other exoplanets are orbiting this star, as indicated by the gravitational influence they have on it. This method remains one of the most effective methods and is used wherever transits are not likely to be observed.

The peculiar nature of TOI 2257 b also makes it a good candidate for follow-up observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWS ). Using its advanced suite of infrared optics, the JWST will observe spectra from transiting exoplanets and characterize their atmospheres. Those planets with a good transmission spectroscopy metric (TSM) will have priority when the JWST begins to gather light in about six months, and TOI-2257 b is one of the most attractive sub-Neptune targets!

Further Reading: University of Bern, Astronomy & Astrophysics