Right now, the Curiosity rover continues to climb Mount Sharp (Aeolis Mons), the central peak within the Gale Crater on Mars. This massive pile of rock and sediment was created over the course of 2 billion years by liquid water that flowed into the crater, creating a layered structure that stands around 5.5 km (18,000 ft) tall. Many of these layers were deposited when the crater is thought to have been a lakebed, which makes it a prime location to search for evidence of past life (and maybe present) on Mars.

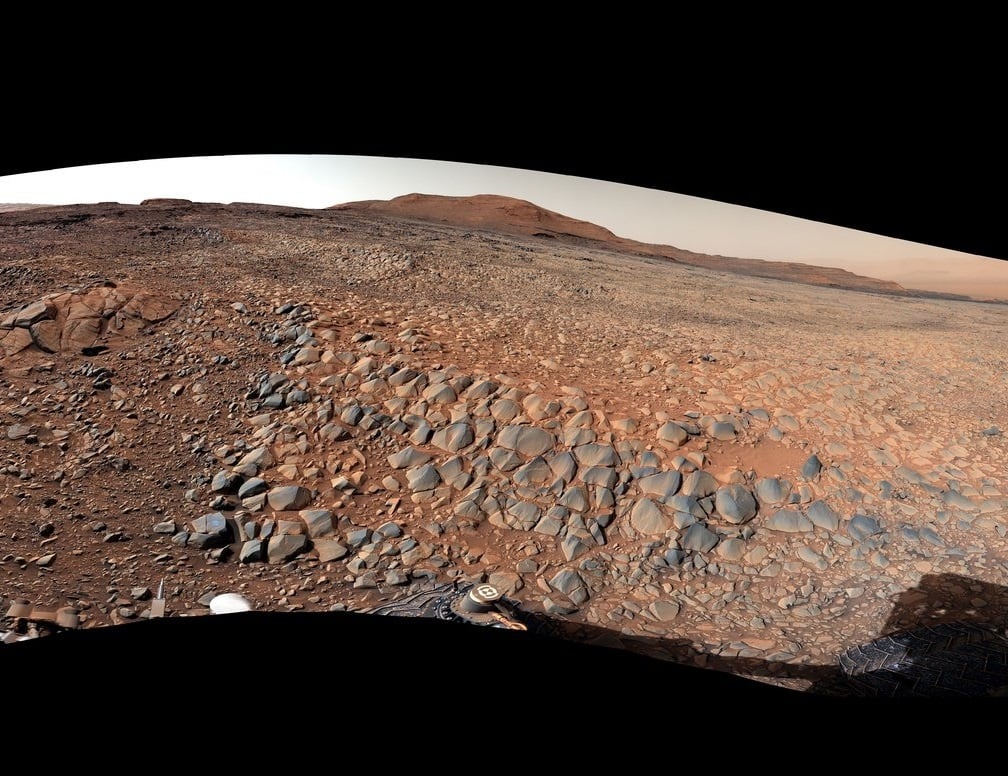

Climbing this feature is hard work and can cause severe wear on Curiosity's metal wheels. The rover began climbing the southern edge of " Greenheugh Pediment," a gentle slope topped by sandstone rubble that scientists want to learn more about. A few weeks ago, the rover suddenly encountered a huge patch of wind-sharpened rocks known as ventifacts (aka. "gator back" terrain). This forced the mission team to plot an alternate route so that Curiosity can continue to get more life out of its wheels.

The Greenheugh Pediment is a broad, sloping plain near the base of Mount Sharp that measures about 2 km (1.2 mi) across (see animation above). Curiosity's mission team first learned of the feature thanks to images taken by NASA orbiters before the rover landed in the Gale Crater in 2012. Scientists are eager to learn more about its formation since it's rich in mineral-bearing clays that form in the presence of water and sticks out as a standalone feature near the base of Mount Sharp.

Curiosity climbed the northern slope of the Greenheugh Pediment two years ago, setting a new record for the steepest terrain it's ever climbed in the process. The rover briefly paused at the summit, which is covered in sandstone rubble, to take many pictures of the path it followed to get there. Recently, the rover navigated its way back onto the Greenheugh Pediment to explore it more fully and perhaps answer questions about where it came from.

On March 18th, the mission team saw unexpected terrain ahead of the rover carpeted with more ventifacts than they had ever seen since the rover landed on Mars almost ten years ago. Ventifacts are sandstone rocks that have been sharpened by wind erosion and are the hardest type of rock encountered by the Curiosity rover. Because of their scalelike appearance, the mission team nicknamed large concentrations of these rocks "gator-back terrain."

Although the area had been scouted using orbital imagery, the team became aware of them only after the rover saw them up close. Curiosity had a similar encounter with "gator-back terrain" in 2017, which led to the first breaks in its wheels. Since then, rover engineers have found ways to mitigate wear and tear and reduce how frequently they need to check the wheels. This includes a traction control algorithm that adjusts the speed of Curiosity's wheels depending on the types of terrain it's climbing.

They also began planning rover routes that would avoid driving over such rocks. Megan Lin is the Curiosity Project Manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which oversees the mission. As she explained in a recent NASA press release, the "gator-back terrain" isn't impassable but is not worth crossing given how much they would age the rover's wheels:

“It was obvious from Curiosity’s photos that this would not be good for our wheels. It would be slow going, and we wouldn’t have been able to implement rover-driving best practices.”

The mission team is currently mapping out a new course for the rover that will allow it to continue exploring Mount Sharp, which Curiosity has been exploring since September 11th, 2014. This tall feature was always intended to be the long-term prime destination for the rover and the last location it would investigate before its original mission ended (planned to last two years). But with Curiosity still going strong after nearly a decade, the rover has been able to revisit locations like Greenheugh Pediment.

Since it arrived in 2012, the Curiosity rover has been joined by such missions as the Perseverance rover, the InSight lander, and China's Tianwan-1 lander and Zhurong rover. In the coming years, it will be joined by the ESA's *Rosalind Franklin* rover, which has been delayed due to the recent termination of cooperation between the ESA and Roscosmos. These missions will continue to study Mars to learn more about its past and help prepare the way for crewed missions in the next decade.

*Further Reading: NASA*

Universe Today

Universe Today