If there are so many galaxies, stars, and planets, where are all the aliens, and why haven’t we heard from them? Those are the simple questions at the heart of the Fermi Paradox. In a new paper, a pair of researchers ask the next obvious question: how long will we have to survive to hear from another alien civilization?

Their answer? 400,000 years.

400,000 years is a long time for a species that’s only been around for a couple hundred thousand years and only discovered farming about 12,000 years ago. But 400,000 years is how long we’ll need to keep this human experiment going if we want to hear from any alien civilizations. That’s according to some new research into Communicating Extraterrestrial Intelligent Civilizations (CETIs.)

The paper is “The Number of Possible CETIs within Our Galaxy and the Communication Probability among These CETIs.” The authors are Wenjie Song and He Gao, both from the Department of Astronomy at Beijing Normal University. The paper is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

“As the only advanced intelligent civilization on the Earth, one of the most puzzling questions for humans is whether our existence is unique,” the authors state. “There have been many studies on extraterrestrial civilization in the past few decades.” There certainly have been, even though it’s difficult to study something we’re not even sure exists. But that doesn’t stop us.

Studying other civilizations in any way is confounding because we only have one data point: humans on Earth. Still, many researchers have tackled the question as a kind of thought experiment, using rigorous scientific guidelines. One study from 2020, for example, concluded that there are likely 36 CETIs in the Milky Way.

How many CETIs might exist is tied up with how long we might have to wait to hear from one. “We have always wanted to know the answers to the following questions. First, how many CETIs exist in the Milky Way? This is a challenging question. We can only learn from a single known data point (ourselves) …” the authors write.

This is where the Drake Equation comes in. Based on our growing knowledge of the Milky Way, the Drake Equation tries to estimate how many CETIs there may be in our galaxy. The Drake Equation has its flaws, as many critics have explained. For example, some of its variables are little more than conjecture, so the number of civilizations it calculates isn’t reliable. But the Drake Equation is more of a thought experiment than an actual calculation. We have to start somewhere, and it gets us started.

It got the authors of this new study started, too.

“Most studies on this problem are based on the Drake equation,” the researchers write. “The obvious difficulty of this method is that it is uncertain and unpredictable to quantify the probability that life may appear on a suitable planet and eventually develop into an advanced communicating civilization.”

If you’re skeptical about any of this, you’re not alone. We can’t know scientifically how many other civilizations there are, or even if any exist. We’re not knowledgeable enough. Studies like this are part of an ongoing conversation we have with ourselves about our predicament. Each one helps us think about the context of our civilization.

So how did they come up with 400,000 years if we don’t even know how many CETIs there might be?

The pair of researchers aren’t the first to tackle this question. Their paper outlines some of the previous scientific efforts to understand the incidence of other civilizations in the Milky Way. For example, they reference a 2020 study estimating that there are 36 CETIs in the Milky Way. That number came from calculations involving galactic star formation histories, metallicity distributions, and the likelihood of stars hosting Earth-like planets in their habitable zones. That paper clarifies that “… the subject of extraterrestrial intelligent and communicative civilizations will remain entirely in the domain of hypothesis until any positive detection is made…” But they also point out that scientists can still produce valuable models based on logical assumptions “… that may at least produce plausible estimates of the occurrence rate of such civilizations.”

This study carries some of that same thinking forward. It deals with two parameters, both of which are poorly understood. The first concerns how many terrestrial planets are habitable and how often life on these planets evolves into a CETI. The second is at which stage of a host star’s evolution would a CETI be born.

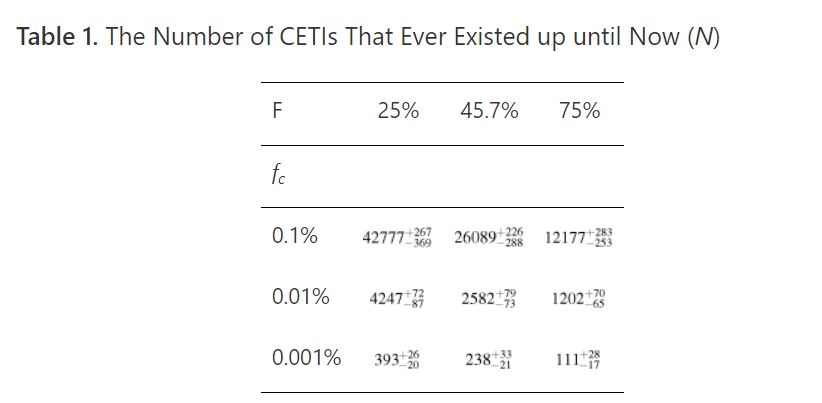

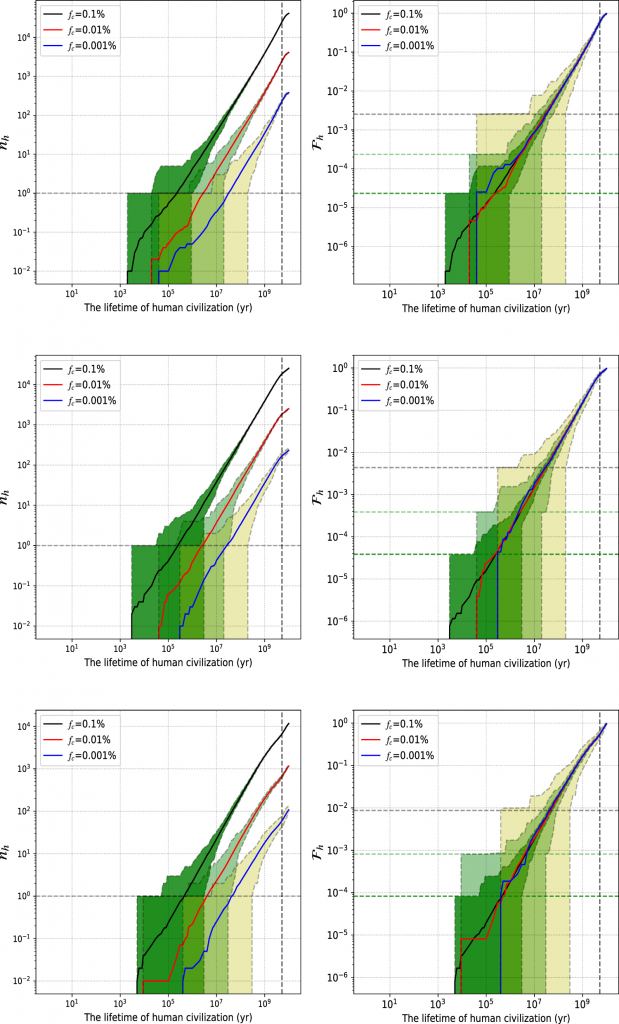

The researchers gave each of these parameters a variable in their calculations. The probability of life appearing and evolving into a CETI is (fc), and the stage of the host star’s evolution required is (F). Song and Gao ran a series of Monte Carlo simulations using different values for these variables. They arrived at two scenarios: an optimistic outlook and a pessimistic outlook.

The optimistic scenario used the values F = 25% and fc = 0.1%. So a star has to be at least 25% into its lifetime before a CETI can emerge. And for each terrestrial planet, there’s only a 0.1% chance of a CETI appearing. These optimistic variables create over 42,000 CETIs, which sounds like a lot, but isn’t when spread throughout the galaxy at different times. Further, we’d need to survive for another 2000 years to achieve two-way communication with us. That almost sounds within reach.

But that’s the optimistic scenario that makes the Universe seem friendly and inhabited by other welcoming civilizations. Maybe some of them are already talking to one another, and we just need to join in.

Now for the pessimistic scenario.

In the pessimistic scenario, F = 75% and fc = 0.001%. So a star can’t host a CETI until it’s much older, and the probability of any single terrestrial planet hosting a CETI drops to a minuscule percentage. Where does this leave us?

This pessimistic calculation produces only about 111 CETIs in the Milky Way. Even worse, we’d need to survive another whopping 400,000 years to have two-way communication with them. (For perspective, Star Trek gets started in the mid-22nd century.)

Here’s where the Great Filter comes in. The Great Filter is whatever hinders matter from becoming life and then progressing to becoming an advanced civilization.

The authors broach that topic when they write, “However, it has been proposed that the lifetime of civilizations is very likely self-limiting, due to many potential disruptions, such as population issues, nuclear annihilation, sudden climate change, rogue comets, ecological changes, etc. If the Doomsday argument is correct, for some pessimistic situations, humans may not receive any signals from other CETIs before extinction.”

In their paper, the scientists write that “… the values of fc and F are full of many unknowns.” That’s the case in all of this type of work. This paper, and others that tackle the same question, are more helpfully seen as thought experiments than as solid results. We can’t know any of this stuff with any certainty, but we can’t help but be compelled to explore it. It’s part of human nature. “It is quite uncertain what proportion of terrestrial planets can give birth to life, and the process of life evolving into a CETI and being able to send detectable signals to space is highly unpredictable,” they write.

Will humanity ever encounter another civilization? It’s one of our most compelling questions, and it’s almost certain that nobody alive today will ever have an answer. First, there have to be other CETIs, and then we have to exist simultaneously with them and communicate somehow. It’s possible that another CETI had already detected life on Earth before they were wiped out by the Great Filter or possibly by a natural calamity like a supernova explosion. We’ll never know.

Maybe humanity will survive a long time. Perhaps Earth will be rendered uninhabitable, and humankind will flee to Mars or somewhere else. But would a Muskian outpost on a long-dead planet, populated by the bedraggled descendants of a ruined Earth, qualify as a CETI? We like to imagine other civilizations having successfully conquered problems that we still struggle with. Will that be true? Or will the first CETI we discover be little more than the descendants of a once-proud civilization that beamed with confidence until the Great Filter struck?

Who knows? If humanity ever does meet another technological species, it could be so far in the future that our descendants are nearly unrecognizable from modern humans.

Or, possibly, we’ll never have an answer, and the Great Filter will stop us from finding one.

But if humanity needs a goal, something to cling to that can keep hope alive, then the dream of communicating with another CETI might do it.