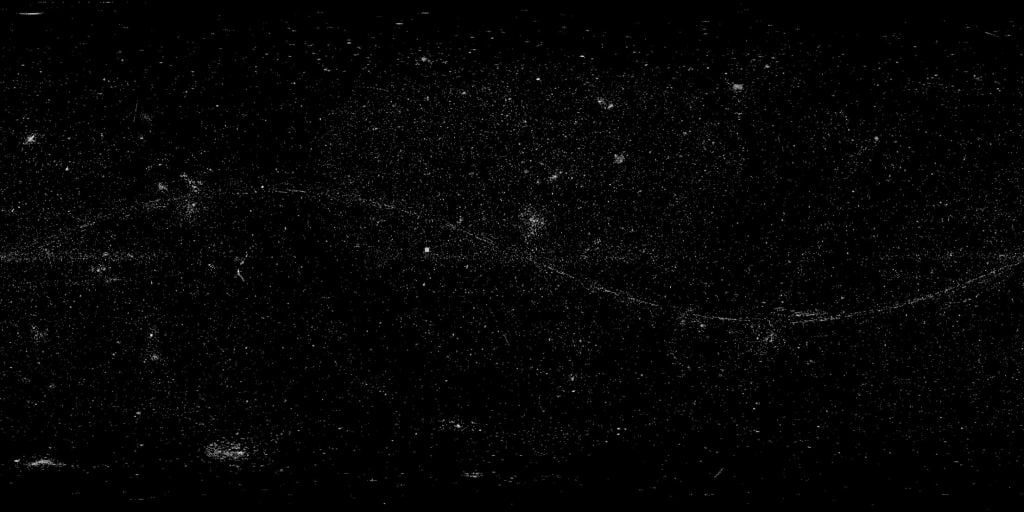

Over the past 32 years, Hubble has made about 1.4 million observations of our Universe. Physicist Casey Handmer was curious how much of the sky has been imaged by Hubble, and figured out how to map out all of Hubble's observations into one big picture of the sky.

It's a gorgeous, almost poetic look at Hubble's collective view of the cosmos. So, how much of the sky has Hubble imaged? The answer might surprise you.

Handmer pondered that question, and determined that since Hubble's field of view is 202 arc seconds, it would take about 3.2 million observations to cover the sky. Since Hubble has made about 1.4 million observations ever since it launched in 1990, would the observatory have imaged about half of the sky? Not quite.

"I ran a basic calculation and I think it's around 0.8% of the entire sky has been exposed to the Hubble imaging system," Handmer said via email, adding that the answer is not as simple as counting the dots in the image because the poles are actually quite stretched on this map.

But why such a small amount? There are a few reasons, Handmer explained. The spectrometer instruments aren't necessarily forming an image, for example. Another reason is that Hubble's field of view is really narrow compared to telescopes that are intended to perform all-sky surveys. But another big reason is that Hubble tends to view certain areas of the sky or certain astronomical objects repeatedly. Why? Because that's what scientists want to see. Some observations take longer than others, and some parts of the sky are more interesting.

In Handmer's image, the curved line across the middle represents the ecliptic, so Hubble's numerous (and repeated) observations of planets, moons and asteroids in our own Solar System show up there.

The two big lumps near the bottom left are the large and small Magellanic clouds, which are two small galaxies that orbit (and are being gradually eaten by) our own. A lot of the other clumps are other nearby galaxies.The disk of the Milky Way galaxy is also visible as a dark U-shaped curve through the middle.

And so, this graphic depicts what Hubble does best.

"Hubble is best used for deep space observations," Handmer said. "It wasn't designed to be an all-sky survey telescope, and so and zooming around would undermine the telescope's ability to stare at really tiny really dim objects for a long time to gain valuable data."

?s=20&t=RiaT7KtFhYkYM8WAesjoSgLoading tweet...

— View on Twitter

By contrast, Handmer noted, the Vera Rubin Observatory (due to begin operations late next year) will image the entire sky every week.

To create this image, Handmer used the astroquery API on the Astropy Library to get data on every observation Hubble has made. The code Handmer used can be found here.

"Each of the observations recovered using the API describes the target, but in the aggregate, we get a picture of what Hubble is looking at," Handmer said. "Hubble is an amazing instrument but it has been in space for almost 32 years and will not last forever. We are fortunate to finally have JWST launched and operating but imagine what we could see if we launched a new telescope like this every year!"

Lead image caption: All of the Hubble Space Telescope's observations from the past 32 years, shown in one graphic. Credit and copyright: Casey Handmer. Used by permission.

Universe Today

Universe Today