Don’t miss one of the top astronomical events for 2022: Sunday night’s total lunar eclipse.

The first eclipse season of 2022 reaches its climax this coming weekend, with a fine total lunar eclipse transpiring on Sunday night into Monday morning. All of South America and most of North America will see the eclipse in its entirety, while Alaska and western Canada will see totality underway at moonrise, and western Europe will see the reverse at moonset near dawn.

The Circumstances for Sunday Night’s Eclipse

Eclipses occur when the nodes where the Moon’s orbit intersect the ecliptic (the plane traced out by the orbit of the Earth) align with the Sun and the Earth, in what’s known as a syzygy. The Moon’s orbit is tilted just over five degrees relative to the ecliptic—otherwise, we’d see solar and lunar eclipses every synodic month (29.5 days). When the nodes are near the Sun-Earth line, an eclipse season occurs. For example, this first season of 2022 was bracketed by the April 30th partial solar eclipse, followed by this coming weekend’s lunar eclipse.

Circumstances for Sunday Night

The Earth’s dark inner umbral shadow is about three times the diameter of the Moon (1.5 degrees across) at the Moon’s average distance from the Earth. You can actually see the curve of the spherical Earth’s shadow crossing the Moon during an eclipse, no special gear needed.

Shadows also have a more subtle penumbral outer edge, inside which the light source is partially visible. From the Earthward surface of the Moon, you’d see a partial solar eclipse during the penumbral phases, and a total solar eclipse during the umbral stage. NASA’s Surveyor 3 did actually manage to grab an image of a solar eclipse from the Moon in 1967:

Perhaps, human eyes could repeat this feat as the Artemis missions return crew to the lunar surface, starting mid-decade.

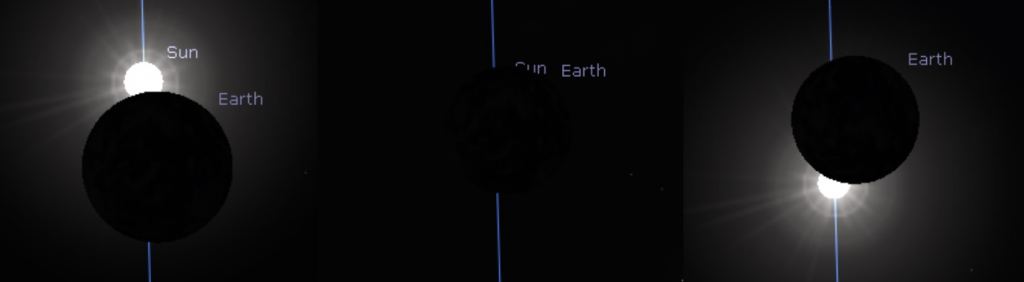

Don’t expect to see too much discernible change in the color of the Moon Sunday night until it’s about mid-way immersed in the penumbra around 10:00 PM Eastern Time (EDT)/2:00 Universal Time (UT). Then, the Moon will take on a light tea-colored hue. Around 2:20 UT, you will note a shading on the eastern limb of the Moon, as it nears the umbra and the partial stages begin.

The key time is totality, and will be a long one for this eclipse, clocking in at 1 hour, 24 minutes and 53 seconds in duration. Totality runs from 3:29 UT/11:29 PM EDT to 4:54 UT/12:54 PM EDT, making it the 5th longest lunar eclipse for the first quarter of the 21st century.

This is not a ‘Super Blood Moon Eclipse…’ though no doubt folks will try to bill it as such. The eclipse actually occurs about a day and a half prior to lunar perigee on May 17th at 15:24 UT, when the Moon is 360,300 kilometers distant.

A lunar eclipse is a fine stately affair, requiring no special optical equipment… though a small telescope or binoculars can certainly enhance the view. Photographing a total lunar eclipse is also pretty easy to do, though you’ll want to use a focal length of at least 200mm—otherwise, the Moon will appear as nothing more than a silvery-white dot. Also, be sure to shoot in manual mode, and be ready to dial down from a fast 1/100th of a second during the partial phases, to a slow 1-4” exposure during totality.

Areas seeing totality underway at moonrise and moonset also provide photographers the chance to nab totality along with foreground objects. Be sure to scout out your site beforehand, and plan on having a generous baseline between yourself and the selected target in front of the Moon: you’ll need to be up to a kilometer away for a building or statue to appear Moon-sized.

None More Red

Not all total lunar eclipses are created equal. The color of the ‘Blood Moon’ can actually vary quite a bit during totality, from a bright saffron yellow disk with a blue-tinged limb, to a dark brick red. The Moon has been known to nearly disappear from view during totality all together, as occurred during the December 1992 lunar eclipse, shortly after the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines. The value used to describe the color and intensity of the Moon as it appears during totality is known as the Danjon Scale running from 4 (bright) to 0 (dark).

This value depends on two factors. One is how centrally the Moon passes through the umbra. During the brief (just under five minute) eclipse on the night of April 4th, 2015, for example, the Moon appeared extremely bright on one limb, sparking a lively debate on the estimated versus actual size of the Earth’s shadow at the Moon’s distance.

The second factor is the amount of dust and aerosols currently suspended in the Earth’s atmosphere, The red you’re seeing during totality is due to the sunlight from a thousand sunrises and sunsets, getting filtered into the cone of the Earth’s shadow from around the rim of the planet. In the past year, eruptions in Tonga and forest fires and dust storms around the world may add to this environmental atmospheric load, resulting in a fairly dark ruddy total lunar eclipse.

Tales of the Saros

All eclipses are part of a saros series, or a set of eclipses will nearly similar circumstances spaced just over 18 years apart. This works because 223 lunations very nearly equals 18 years, 11 days and 8 hours (just shy of 17 minutes, in fact), with each successive eclipse in the same saros series shifted about 120 degrees westward. The Babylonians knew of the saros cycle, and used it to predict eclipses. The Greeks also knew of the saros cycle of eclipses, and built this knowledge in to the famous Antikythera mechanism used to predict future eclipses.

Saroses evolve over time, starting as shallow penumbrals, then becoming central total eclipses before receding. This weekend’s eclipse is member 34 of the 72 eclipses in lunar saros series 131. This series started waaaay back on May 10th 1427, and will produce its last total lunar eclipse on September 3rd 2202, before ending on (mark your calendars) July 7th 2707 AD.

There are also a few fun projects to carry out during a lunar eclipse. One is a long-standing effort to time when specific lunar craters enter the umbra, in an effort to refine the established diameter of the Earth’s shadow.

Another is to attempt to measure your longitude during an eclipse. This method was used by mariners such as Captain James Cook and (possibly) Columbus. It works because the eclipse gives you a good one-time ‘time hack,’ allowing the observer to gauge the position of the eclipsed Moon in the sky, versus a known prediction from a table made for a land-based observatory.

It’s also worth keeping an eye out and reviewing images and video for meteors striking the eclipsed Moon. Just such an event during the January 2019 eclipse and sent lots of us scrambling, to see if we also caught the flash on the lunar limb. This weekend, there’s a chance that a Herculid meteor outburst courtesy of asteroid (nee comet?) 2006 GY2 may be active, so it’s a good idea to watch for any spurious meteor activity.

Transits and Occultations

Also, be sure to watch for things passing in front of (and behind) the eclipsed Moon. Astrophotographer Chris Becke notes that though we do not have a favorable ISS transit for the U.S. during the eclipse, we do have a transit of China’s new Tiangong Space Station crossing the United States around the start of totality:

If you want to see the ISS transit the eclipsed moon this Sunday night, you’re out of luck due to an unfavorable orbit. But if you live along this line, you may see the Chinese Space Station transit near the beginning of totality. check https://t.co/SSpjvNJprT@Astroguyz pic.twitter.com/YAp1a3uXJ2

— Christopher Becke (@BeckePhysics) May 9, 2022

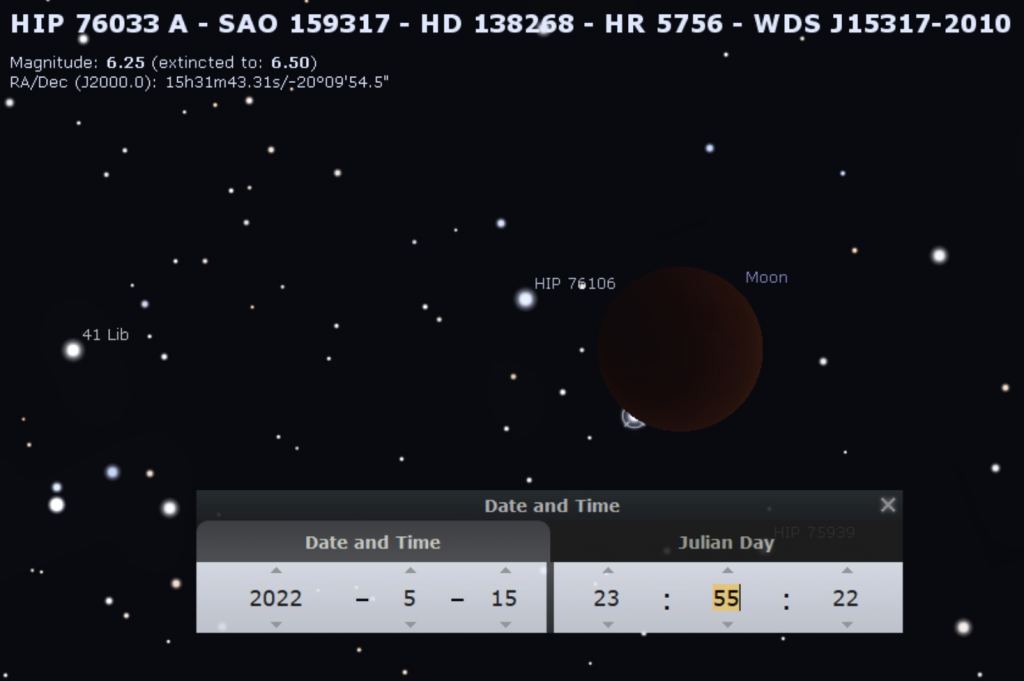

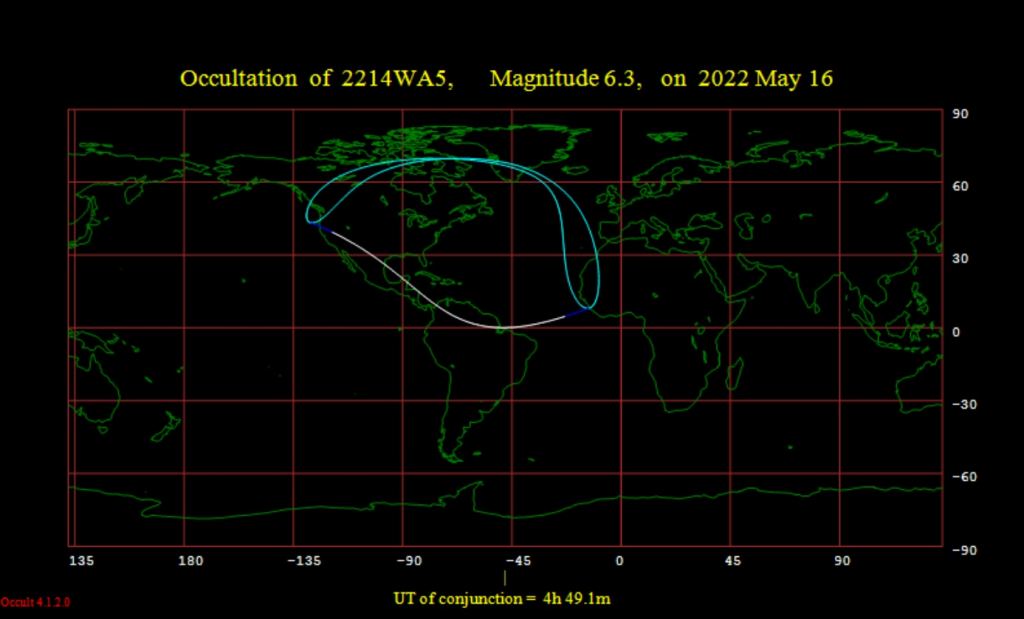

Also, the Moon will occult the +6.3 magnitude double star SAO 159317 in the constellation Libra the Scales for North America during totality. This will be a good practice run observation for a rare event later this year during the next total lunar eclipse on November 8th, when the Moon occults the planet Uranus near totality.

Finally, another unique observation to try to see during a total lunar eclipse is to nab the elusive selenelion, or seeing the totally eclipsed Moon and rising Sun above the horizon at the same time. This works because the umbra of the Earth is bigger than the Moon, and the Earth’s atmosphere refracts light from both. You’ll need high ground and an absolutely clear horizon to carry out this unique feat of astro-athletics. The best regions to try this during Sunday night/Monday morning’s eclipse are between the U2-U3 contact zones (see the world eclipse map earlier in this article). These swaths cover western Canada at sunset, and Iceland, the United Kingdom, France and central Africa at dawn.

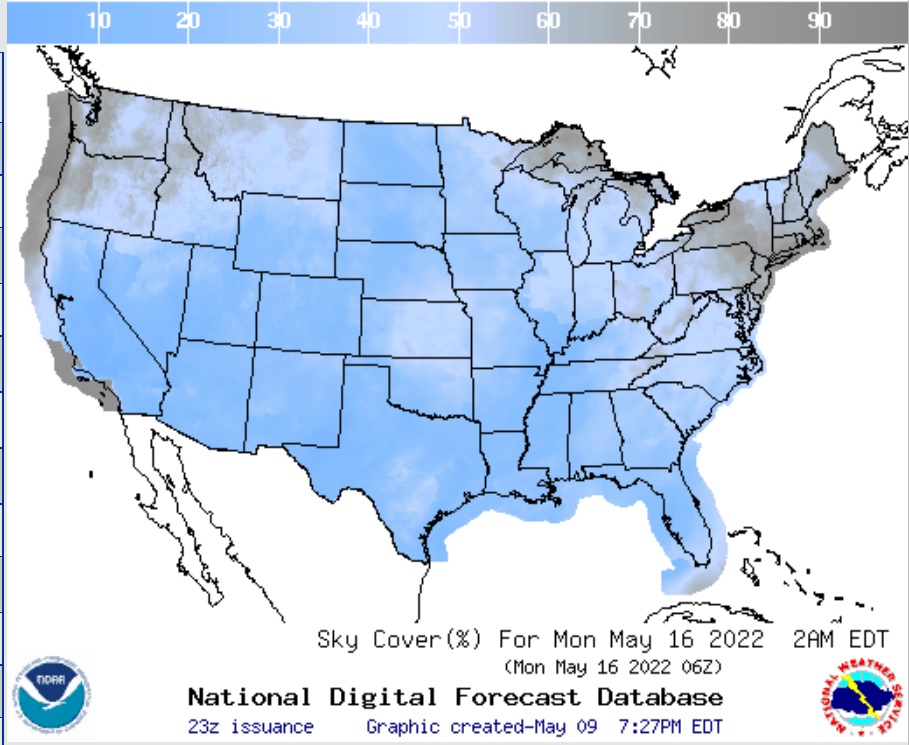

We’re also keeping a close eye on weather prospects this weekend, leading up to the eclipse. Keep in mind, you’d don’t need a crystal-clear sky to enjoy a lunar eclipse… just a good clear view of the Moon.

Clouded out, or simply live in the wrong hemisphere? The good folks at the Virtual Telescope Project have got you covered, with a live webcast of the total lunar eclipse hosted by astronomer Gianluca Masi starting on May 15th at 2:15 UT/10:15 PM EDT.

Don’t miss the first total lunar eclipse of 2022!

Lead image credit: A mosaic of the November 2021 total lunar eclipse. Image credit and copyright: Christopher Becke.