Scott Alan Johnston (that’s me!) joined the Universe Today team just over a year ago. Since then, I’ve written over 50 space news stories for the website – time flies when you’re having fun! But when I’m not writing articles here on Universe Today, I’m a historian of science, and I recently released a new book about the history of timekeeping.

Have you ever wondered why we tell time the way we do? Well, history buffs, come along for a journey:

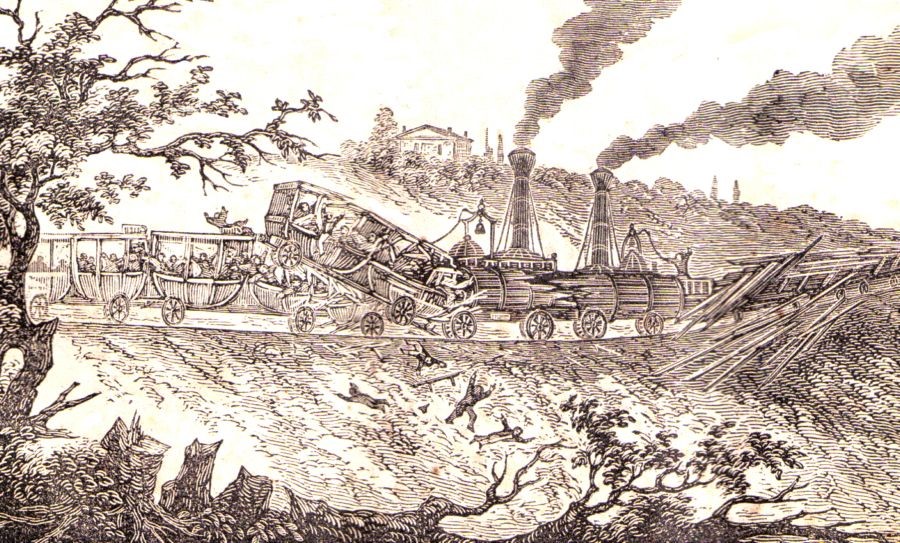

For nearly all of human history, time was a local matter. On foot or horseback, you couldn’t travel fast enough from one town to the next to care that noon was occurring a few minutes earlier or later. But that all changed in the mid-19th century, with the invention of the train. Suddenly, for the passengers on those chariots of steam and coal, time differences became a matter of life and death.

The invention of the telegraph further exasperated things – suddenly, information could travel around the globe unimaginably fast. Clearly, local time wasn’t going to cut it anymore: a global timekeeping standard was going to be necessary. But how do you make everyone agree what time it is? That’s where The Clocks are Telling Lies picks up the story: the quest for a shared universal time.

While railroad engineers like Sandford Fleming and William Allen sought to establish time zones to keep their cross-continental trains running smoothly, astronomers around the world were engaged in their own time-keeping challenges. The transit of Venus – a rare twice in a century event – was set to occur in 1874, and again in 1882. Multinational expeditions to observe the transits would be futile without a way to compare the timing of the observations. Meanwhile, meteorologist Cleveland Abbe faced a similar challenge as he tried to study the northern lights with a team of volunteers – each observer used their own local time, making it impossible to draw useful comparative conclusions from the various observations. A new solution was clearly required.

It’s in this context that astronomers and engineers (and politicians) from around the world came together to decide how best to manage the planet’s timekeeping. They gathered in Washington DC at the International Meridian Conference of 1884, a diplomatic conclave whose messy conflicts form the climax of the book. Here, nations fought each other over the right to host the Prime Meridian, while astronomers fought engineers over whether to adopt a single global time, or twenty-four distinct time zones. The conference was divisive and inconclusive, leaving more questions than answers: we’re still feeling the results of those deliberations today.

If there’s a moral to The Clocks are Telling Lies, it’s that new things don’t push aside the old – they coexist. Local timekeeping practices continued to survive alongside universal time. Perhaps more importantly, nothing is universal without universal access – just because universal time was ‘invented’ didn’t mean everyone suddenly had the means to use it. This is an important lesson for the modern world too. Think, for example, of the internet: 37 percent of the global population has never used it! Imagine the implications – all that knowledge at your fingertips! But inequality keeps it out of the hands of those who might benefit most from it. The tools and technologies we invent are only as helpful and valuable as they are shared and made accessible to those who need them.

So, there you have it. The Clocks are Telling Lies is available in places where they sell books (like Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and Indiebound). And hey – as the author, I concede the book may not be everyone’s cup of tea. It’s scholarly (you know, with footnotes and stuff), so light reading it isn’t. But if you want to dig deep into the subject, you won’t regret giving it a go.

Some other things you’ll find in The Clocks are Telling Lies:

- How an eccentric astronomer tried to establish the Great Pyramid of Giza as Prime Meridian for the world.

- An eight-month standoff in which Britain’s Astronomer Royal held Greenwich Time hostage from the Admiralty and Navy in an attempt to force an increase in the observatory’s budget.

- The story of Ruth and Maria Belville, entrepreneurs who sold the time door-to-door in London for nearly a century.

- An 1893 court case in which a pub won the right to serve drinks according to local solar time, rather than standard time, pushing their nightly last call about 30 minutes later than the competition.