Astronomers have a brown dwarf problem. They should be seeing a lot more of these objects, which are cooler than stars but hotter than planets. Yet, there have only been about 40 directly imaged over the past few decades. Why aren’t astronomers finding more of them? It helps to remember that brown dwarfs are dim, low-temperature objects. They don’t stand out in a crowded starfield. If they’re too close to their stars, the starlight hides them from our view. They’re much better observed in the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum. All these characteristics make hunting for them difficult.

Searching Out Brown Dwarfs

The difficulty of finding brown dwarfs leads to what astronomers call the “Brown Dwarf Desert” problem. The deal is, there should be more of them, and there probably are. Most surveys hunting for brown dwarfs so far have targeted random stars from young clusters or looked in regions where hot young stars are being born. Those seem to be likely places to hunt for brown dwarfs. Hubble found a bunch of them in the Orion Nebula, using an infrared instrument to get images.

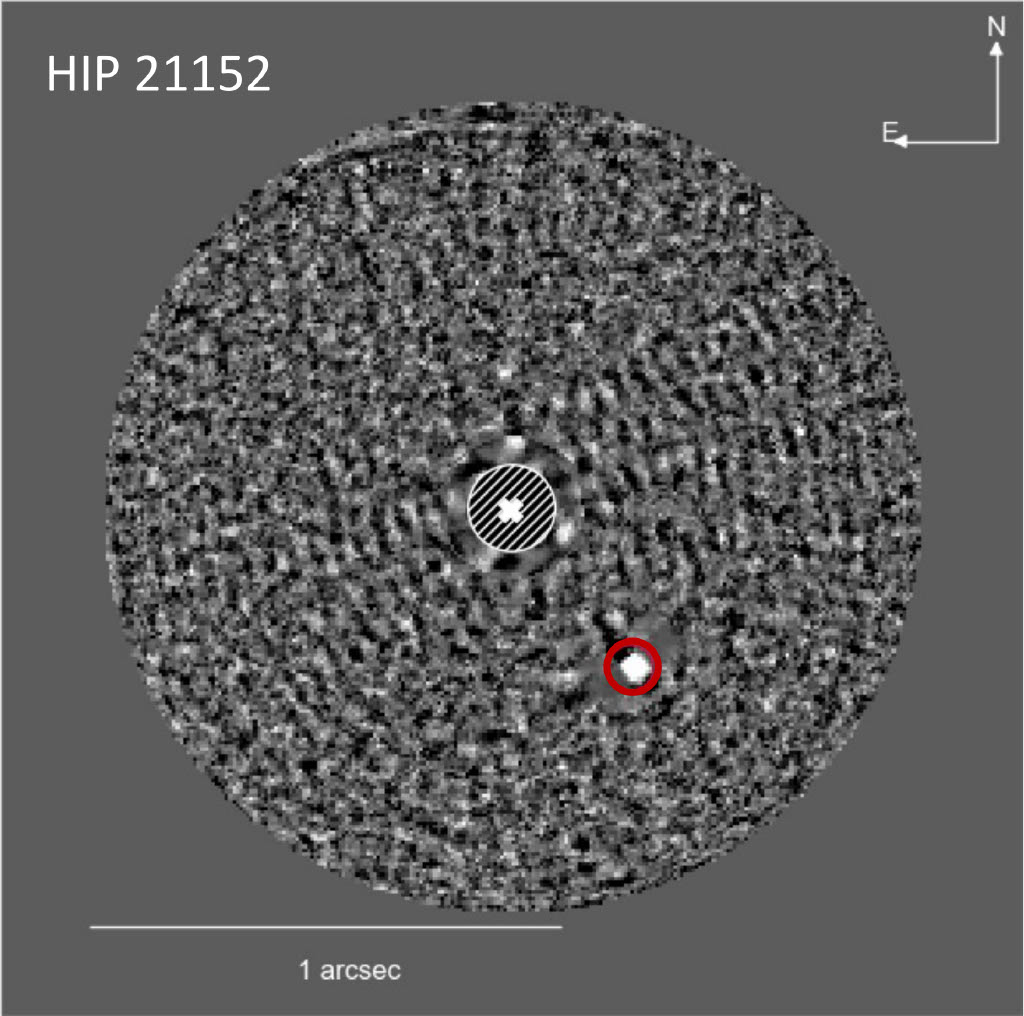

There is another solution at hand. Astronomers led by Mariangela Bonavita from the Open University and Clémence Fontanive from the Center for Space and Habitability (CSH) and the NCCR PlanetS at the University of Bern have found four more brown dwarfs by using GAIA spacecraft data to search for likely candidate stars. Then, they directly imaged them using the SPHERE planet-finder on the Very Large Telescope in Chile.

Looking Far From Stars for Brown Dwarfs

The team beat the odds by looking for what’s called wide-orbit brown dwarfs. They travel far from their stars which makes them easier to find once you know where to look. “Wide-orbit brown dwarf companions are rare to start with, and detecting them directly poses huge technical challenges since the host stars completely blind our telescopes”, said Bonavita. She and her team developed a tool called COPAINS (Code for Orbital Parameterisation of Astrometrically Inferred New Systems) to look for previously undiscovered companions of stars.

“An alternative approach to increase the number of detections is to only observe stars that show indications of an additional object in their system”, explained Fontanive. For example, the way a star moves under the gravitational tug of a companion can be an indicator of the existence of that companion, whether it is a star, a planet, or something in between. This is where the COPAINS tool came in handy. It predicts the types of companions that might tug on a star and influence its motions.

Success and More in the Brown Dwarf Hunt

It helped the group select a target group of 25 nearby stars from GAIA data. These were stars the team suspected might have low-mass companions. The next step was to observe them using the VLT. The team actually got more than they bargained for. In addition to the four directly imaged brown dwarfs, they found five low-mass stars and a white dwarf. So, not only did this technique add to the number of wide-orbit brown dwarfs, but the astronomers demonstrated a viable way to continue the hunt for these elusive objects. If it’s applied widely, it might solve the problem of the brown dwarf desert.

“This result was only possible because we believed that, when combining space and ground-based facilities to directly image exoplanets, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” said Bonavita. “We hope that this will be the start of a new era of synergy between different instruments and detection methods.”

For More Information

Ground-breaking Number of Brown Dwarfs Discovered

A New Method for Target Selection in Direct Imaging Programmes with COPAINS