The Orion Nebula is a well-known feature in the night sky and is visible in small backyard telescopes. Orion is a busy place. The region is known for active star formation and other phenomena. It's one of the most scrutinized features in the sky, and astronomers have observed all kinds of activity there: planets forming in protoplanetary disks, stars beginning their lives of fusion inside collapsing molecular clouds, and the photoevaporative power of massive hot stars as they carve out openings in clouds of interstellar gas.

But supernova explosions are leaving their mark on the Orion Nebula too. New research says supernovae explosions in recent astronomical history are responsible for a mysterious feature first formally identified in the night sky at the end of the 19th century. It's called Barnard's Loop, and it's a gigantic loop of hot gas as large as 300 light-years across.

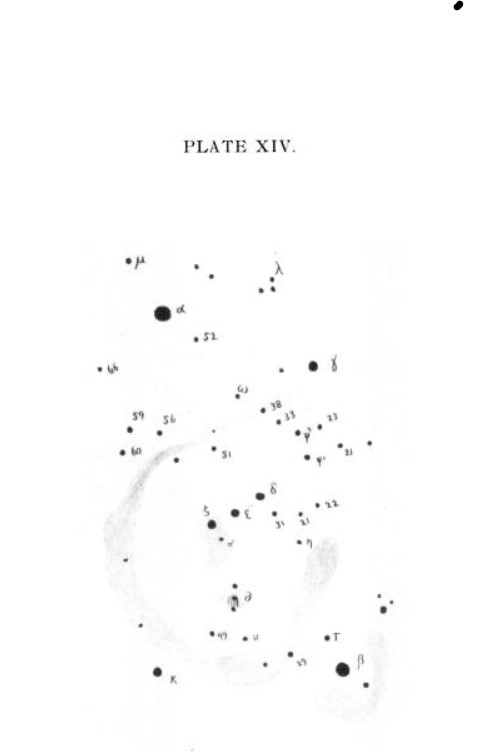

In 1894, American astronomer and astrophotographer E.E. Barnard published his observations of Orion in Popular Astronomy. Remarkably, he was experimenting with the lens from a "cheap, oil-projecting lantern"—in his words—that he used at the Lick Observatory. In his article, he explained what he'd found. "On my drawing, I have marked a portion of the nebulosity, from one degree to two degrees east of Tau, with dots, as it is so feeble at this point that I cannot be certain of it." He added that "It is brightest near 56 and 60 Orionis." (Barnard also acknowledged that he wasn't the first to see it.)

In our more modern times, we simply point our browsers and gorgeous images of Barnard's Loop quickly pop up on our screens.

Astronomers' understanding of Barnard's Loop has progressed along with our observational power and our growing knowledge of everything in nature.

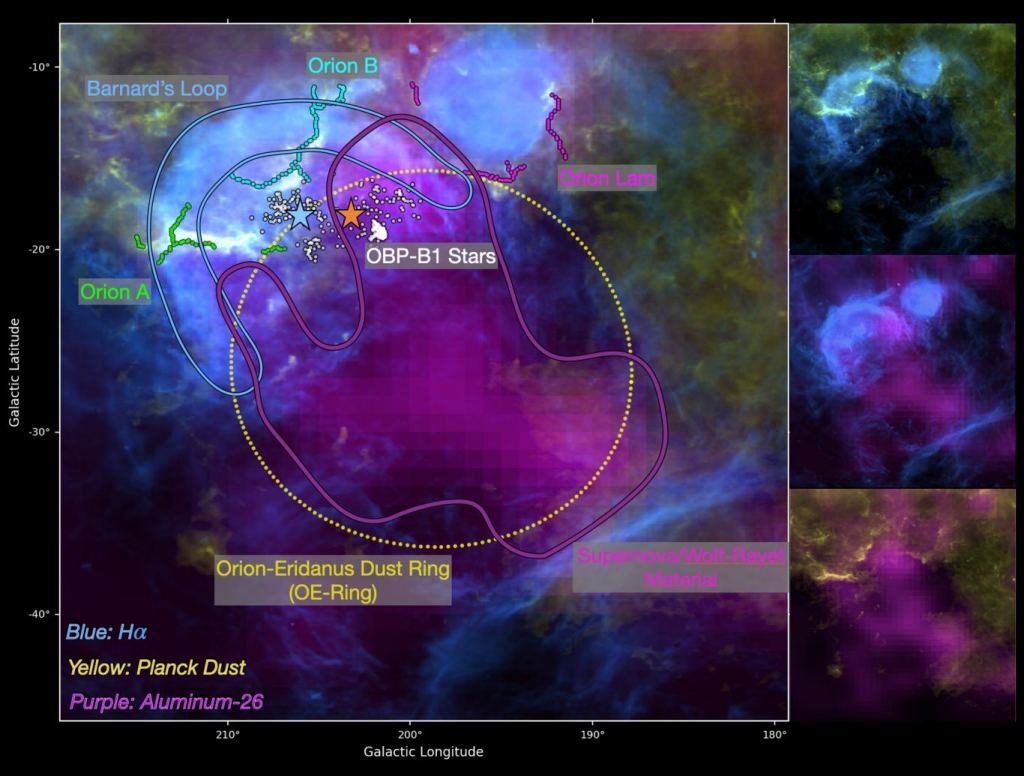

We know that it's an emission nebula made of ionized gases. The gases emit light of different wavelengths, though red alpha-hydrogen is dominant. We know that the nearby stars in the Orion nebula are powering the ionization of the gases and their emissions. One thing astronomers haven't been certain about is what created the loop of gases in the first place.

The most likely cause is a supernova explosion. A new paper backs that up, saying that at least one supernova carved out features in the region sometime in the last four million years.

The paper is " A 3D View of Orion: I. Barnard’s Loop " and it's available online at the pre-press site Authorea. The lead author is Michael Foley, a grad student at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. The team presented their results at a press conference hosted by the American Astronomical Society.

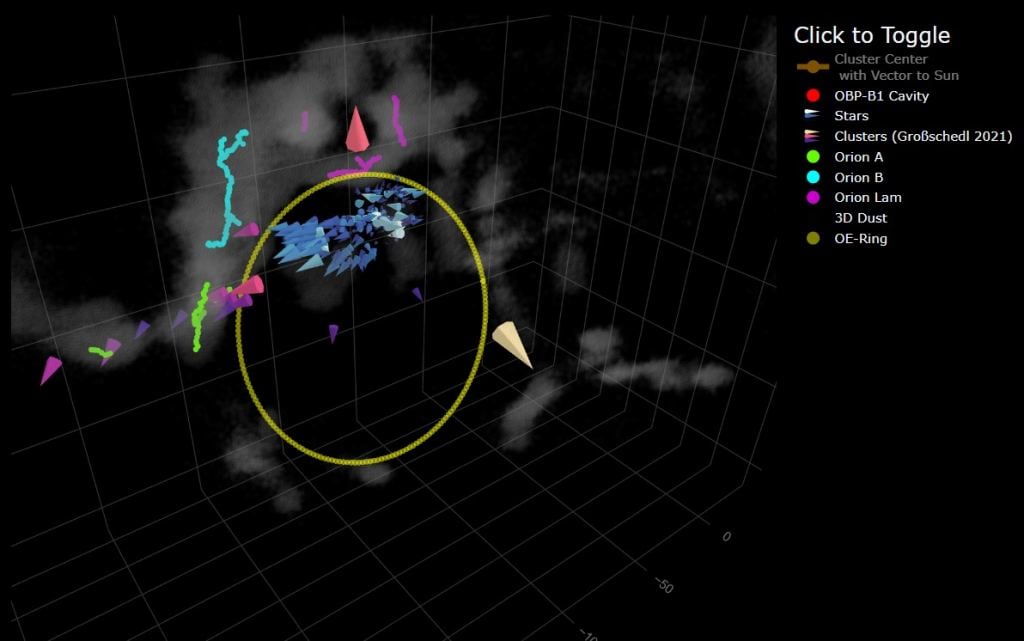

The ESA's Gaia spacecraft played a role in this research. Gaia is an ambitious project to create a 3D map of the Milky Way, and the project just released its third data set. This research team is known for creating interactive figures that help bring their research to life, and when they combined existing 2D data with Gaia's 3D data, the team was able to map out more of the busy Orion region in their interactive tool.

"Our first large-scale 3D look at Orion tells us so much," said lead author Michael Foley. "Prior to this work, most studies of Orion were confined to two dimensions — up-down and left-right on the sky. By adding in the third dimension — distance — we can begin to map out all sorts of interesting structures, like huge cavities of gas and dust or clusters of stars with very interesting motions. Combining the information from the interstellar gas and stars leads us to believe cavities were produced by a number of supernovae over the last few million years."

"Orion has had quite an exciting history," he added.

The team's interactive visual tool is based on visualization software called Glue. It shows a cluster of stars moving outward from a point close to the center of Barnard's Loop. They think that one or more supernovae explosions created the Loop and propelled the stars outward. The position and velocity data show this happened sometime in the last four million years.

Another clue lies in the formation of new stars on the edges of Barnard's Loop's cavity. Supernovae generate powerful shock waves that compress gas and can trigger star formation.

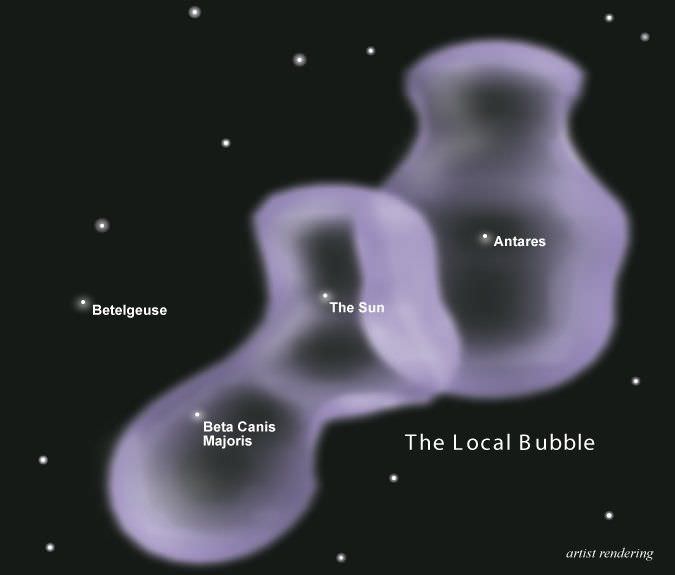

Their results don't stand alone. Other research, including previous research by the same team, show that supernovae are responsible for carving out other bubbles in the interstellar medium and triggering widespread star formation. This is true of the Per-Tau gas shell that's surrounded by the Perseus and Taurus molecular clouds. And the more astronomers use sophisticated data like that from Gaia, the more they will find these gas bubbles with pronounced star formation on their edges, according to co-author Alyssa Goodman.

"It seems clear that we are going to see a 'swiss cheese' picture of the interstellar medium, with stars forming at the edge of the holes, as we map more and more of the galaxy," said Alyssa Goodman, a Harvard professor, CfA astronomer and co-author on the study.

"We believe that shells and loops in Orion, the Per-Tau shell, and the Local Bubble are the first of many discoveries relating new star formation to old supernovae, Foley says. "Supernovae sweep up gas and dust into dense clumps, leading to the perfect birthplaces for new stars. The Orion region, rich in both star formation and supernovae, is the latest example of that."

Thanks to the ESA's Gaia mission and powerful computing resources in the hands of astronomers and data visualization experts, we're getting more sophisticated and detailed 3D looks at the Universe. The Orion Nebula and its region is a great place to start because there's so much going on there: stars are born, and some die in catastrophic explosions that trigger more star birth. But a 3D Orion is just the beginning to Foley, whose enthusiasm is overflowing.

"Thanks to the work of many incredible scientists, 3D data will transform our understanding of star formation in our galaxy," Foley notes. "It may be much more explosive than we even imagine!"

This new paper is the first in a series from this group of researchers. The next one will supernovae present throughout the larger Orion region. Expect more Swiss cheese.

More:

- Press Release: Did Supernovae Help Form Barnard's Loop?

- New Paper: A 3D View of Orion: I. Barnard's Loop

- Universe Today: Newborn Stars in the Orion Nebula Prevent Other Stars from Forming

Universe Today

Universe Today