Searching for a comfortable place to set up a research station on the Moon? Look no further than the interior parts of lunar pits and caves. While lack of air will be an issue, new research indicates these underground sanctuaries have steady temperatures that hover around 17 Celsius, or 63 Fahrenheit, even though the Moon’s surface heats up to about 127 C (260 F) during the day and cool to minus 173 C (minus 280 F) at night.

Lunar pits, or lava tubes were discovered in 2009 by the Lunar Reconnaissance Obiter and Japan’s Kaguya spacecraft. These are deep holes on the moon that could open into vast underground tunnels. They likely could serve as a safe shielding from cosmic rays, solar radiation and micrometeorites for future human lunar explorers. But now we know they could provide thermally stable sites for lunar exploration.

These long, winding lava tubes are like structures we have on Earth. They are created when the top of a stream of molten rock solidifies and the lava inside drains away, leaving a hollow tube of rock. For years before their existence was confirmed, scientists thought there were hints that the Moon had lava tubes based on observations of long, winding depressions carved into the lunar surface by the flow of lava, called sinuous rilles.

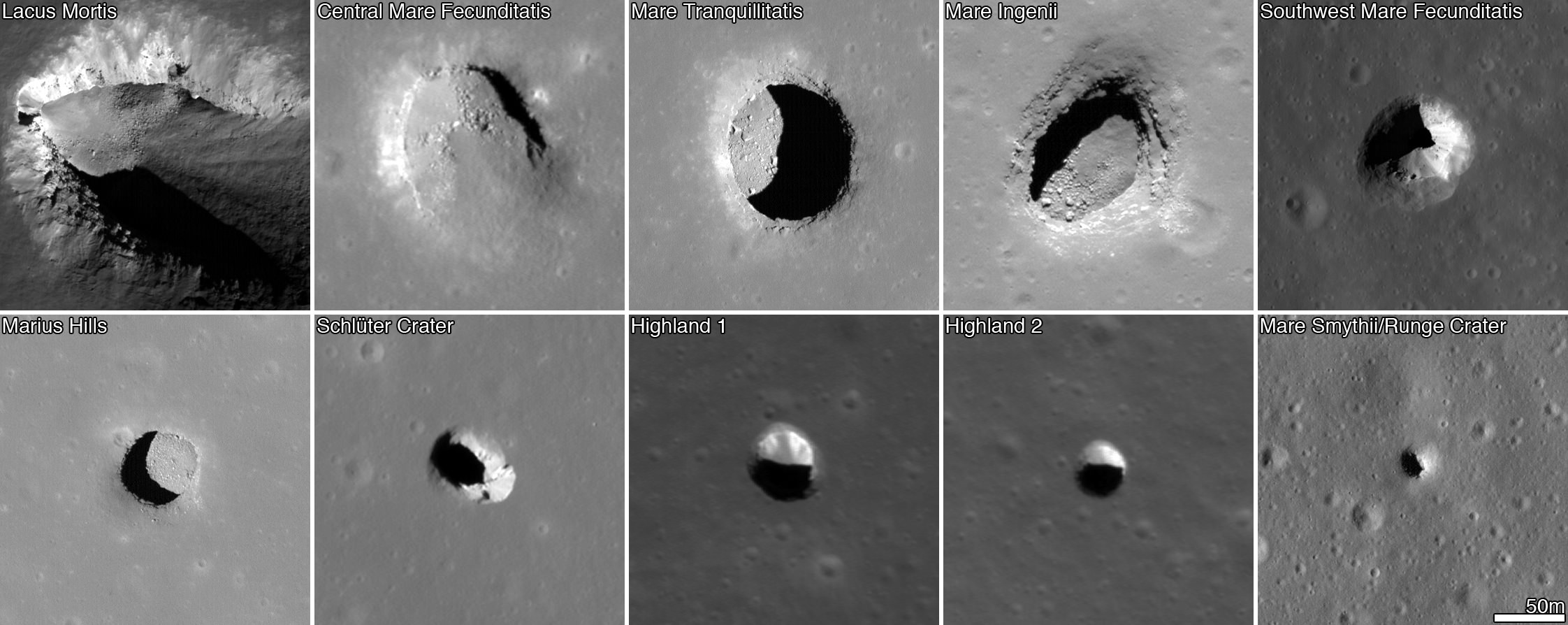

So far, about 200 lunar pits have been found and at least 16 of these are probably collapsed lava tubes, with the potential for ‘livable’ space, said Tyler Horvath, a UCLA doctoral student in planetary science, who led the new research. Two of the most prominent pits have visible overhangs that clearly lead to some sort of cave or void, and there is strong evidence that another’s overhang may also lead to a large cave.

Horvath processed images from the Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment — a thermal camera and one of six instruments on LRO — to find out if the temperature within the pits diverged from those on the surface. Diviner is designed to measure surface temperatures on the Moon, and Horvath’s team had to focus in on extremely small areas to get their data.

They focused on a pit found in the Sea of Tranquility (Mare Tranquillitatis). This image, below, was taken as the Sun was almost straight overhead, illuminating the region. By comparing this image with previous images that have different lighting, scientists can estimate the depth of the pit. They believe it to be over 100 meters.

Credits: NASA/Goddard/Arizona State University

The researchers used computer modeling to analyze the thermal properties of the rock and lunar dust and to chart the pit’s temperatures over a period of time. Their research, recently published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, revealed that temperatures within the permanently shadowed reaches of the pit fluctuate only slightly throughout the lunar day, remaining at around 17 C (63 F). If a cave extends from the bottom of the pit, as images taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera suggest, it too would have this relatively comfortable temperature. The researchers think the overhang is responsible for the steady temperature, limiting how hot things get during the day and preventing heat from radiating away at night.

However, if this particular pit was to be used as a habitat or research station, there would likely be a heat problem just inside the pit. The sunbaked part of the pit floor not protected by the overhang hits daytime temperatures close to 150 C (300 F), which is even hotter than the Moon’s surface.

“Because the Tranquillitatis pit is the closest to the lunar equator, the illuminated floor at noon is probably the hottest place on the entire moon,” said Horvath.

Since a day on the Moon lasts nearly 15 Earth days, the lunar surface is constantly bombarded by sunlight and is frequently hot enough to boil water. Conversely, the equally long lunar nights (also 15 Earth days long) reach incredibly cold temperatures. Any habitat or base would mean inventing heating and cooling equipment that can operate under these conditions, as well as ways to produce enough energy to power it nonstop. This could prove to be an insurmountable barrier to lunar exploration or habitation.

However, the researchers say that building bases in the shadowed parts of these pits allows scientists to focus on other challenges, like growing food, providing oxygen for astronauts, gathering resources for experiments and expanding the base.

“Humans evolved living in caves, and to caves we might return when we live on the moon,” said UCLA professor of planetary science David Paige, who leads the Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment and participated in the research.

Further reading: Press releases from UCLA and NASA, and the team’s research paper