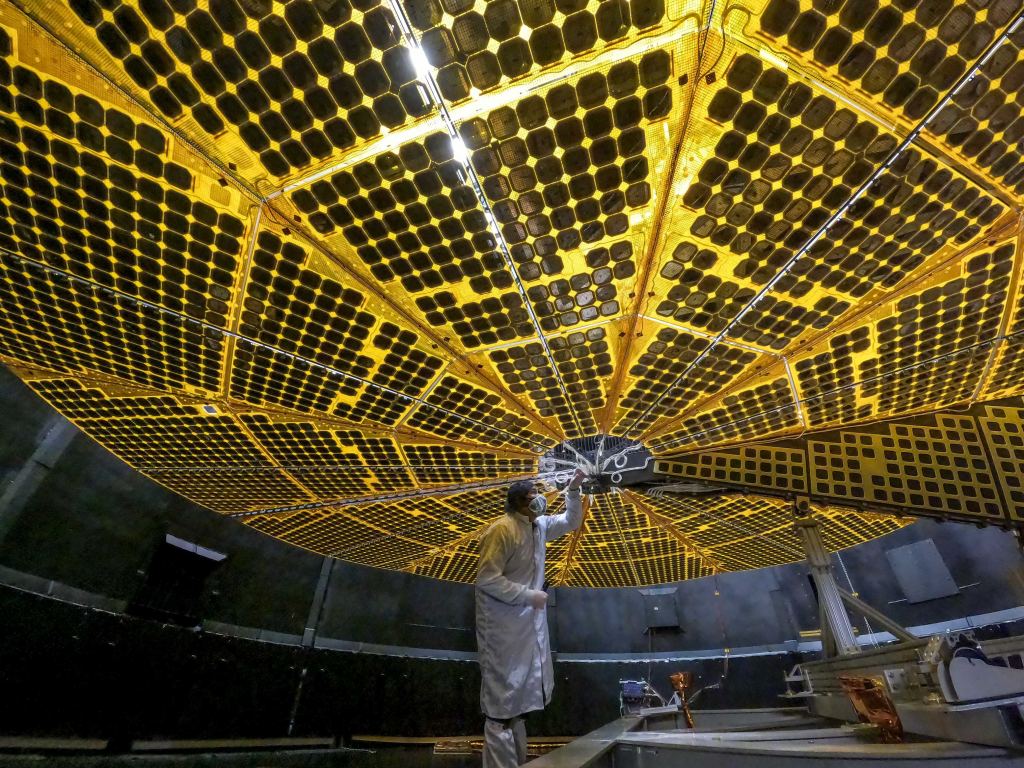

How do you fix the solar array of a spacecraft millions of miles away from the Earth hurdling through the void at thousands of miles per hour? Very carefully, that's how.

Shortly after Lucy launched, engineers at NASA realized that there was a problem. A spacecraft sent to investigate the Trojan asteroids of Jupiter, Lucy relies on two massive solar arrays which were folded up like a fan during lunch. One of the arrays unfolded successfully, but the other failed to do so.

Immediately questions came up. Even though the other solar array was roughly 90% deployed, it was not properly latched. Would Lucy be able to achieve all of its science objectives with that reduction in power? Would the maneuvers required by the spacecraft and the rigors of the interplanetary space cause the partially folded array to come loose and potentially damage the spacecraft?

In response to these questions NASA created a team in partnership with Lockheed Martin, who had developed the spacecraft. Their first assignment was to discover what had gone wrong.

"This is a talented team, firmly committed to the success of Lucy," said Donya Douglas-Bradshaw, former Lucy project manager from NASA Goddard. "They have the same grit and dedication that got us to a successful launch during a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic."

To remotely diagnose the issue the team sent commands to Lucy to fire some of its thrusters in different directions at different times. Using onboard sensors they could determine how the spacecraft vibrated in response to those thrusts and maneuvers and from there pinned down what had gone wrong.

"We have an incredibly talented team, but it was important to give them time to figure out what happened and how to move forward," said Hal Levison, Lucy's principal investigator from SwRI. "Fortunately, the spacecraft was where it was supposed to be, functioning nominally, and – most importantly – safe. We had time."

The team discovered that the wire used to pull the solar array open had gotten snagged, leaving the solar array only partially deployed.

After more deliberations the team came up with a couple potential solutions. One solution was to leave it as it was. The array was 90% deployed after all, and any attempt to fix it may cause further damage to the spacecraft. So was an attempted fix even worth the risk?

"Each path carried some element of risk to achieve the baseline science objectives," said Barry Noakes, Lockheed Martin's deep space exploration chief engineer. "A big part of our effort was identifying proactive actions that mitigate risk in either scenario."

The team ultimately settled on a second solution. Lucy had a second backup spool to pull the array open in case the first spool failed. If both spools worked together, they might be strong enough to unstick the jam and pull the array open.

The team then spent months working with simulations and replicas to make sure that both spools could work in tandem without damaging the craft. Feeling confident, they attempted four dual unspooling attempts over the course of a few months.

"The cooperation and teamwork with the mission partners was phenomenal," said Frank Bernas, vice president, space components and strategic businesses at Northrop Grumman.

Overall, their plan worked. The second solar array isn't latched, but it is over 99% open and under a much greater amount of tension. The team believes that the array will remain stable throughout the duration of the mission .

Lucy is scheduled to perform a gravity assist flyby of the Earth in October 2022 and arrive at her first mission target in 2025.

Universe Today

Universe Today