This is it, folks. Feast your eyes! It's what we've been training for—seeing the James Webb Space Telescope's first detailed view of the Orion Nebula! JWST's NIRCam gazed at this starbirth nursery and revealed incredible details hidden from view by gas and dust clouds.

The images of the nebula come from a research project called the P hoto d issociation R egions for All. It's part of the telescope's Early Release science program. A number of astronomers around the world are part of the PDRs4All group, and they've planned these observations for a long time. "We are blown away by the breathtaking images of the Orion Nebula. We started this project in 2017, so we have been waiting more than five years to get these data," said Western astrophysicist Els Peeters, who is part of the group.

Diving into the Orion Nebula

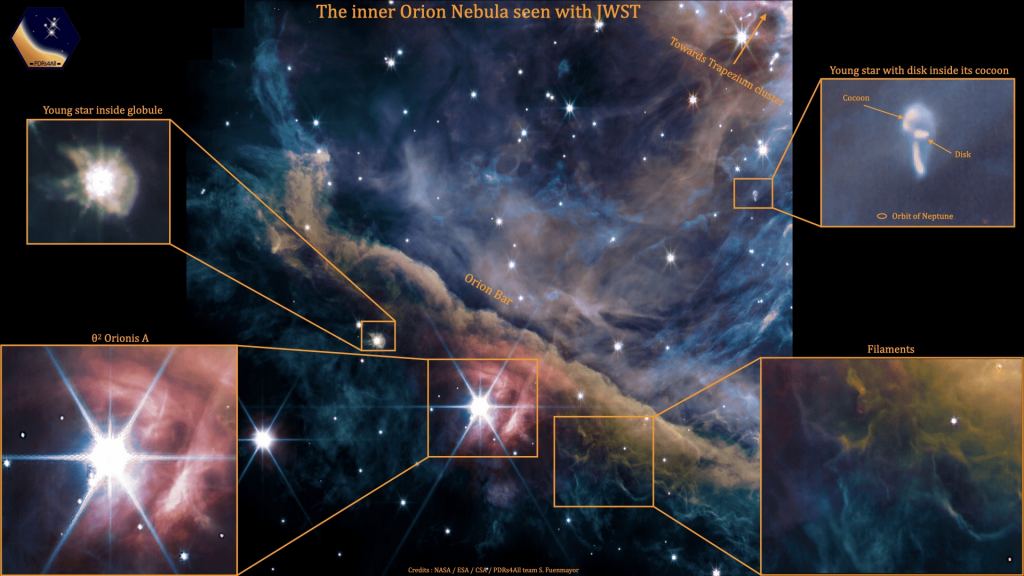

So, where exactly did JWST point and what did it search out? The Orion Nebula we all know and love exists within a larger object called the Orion Molecular Cloud. The central section lies in the middle of the Orion constellation, just below the three stars that form its belt. JWST zeroed in on a smaller, innermost region right near a grouping of stars called The Trapezium. Its observation was planned in order to capture what happens in star birth regions.

Light from the Trapezium stars (not seen in the JWST image below) lights up the view. The Trapezium and other young stars in the region give off strong ultraviolet (UV) radiation. It eats away at the clouds of gas and dust in a process called "photodissociation". In particular, the UV light is eroding a feature called the "Orion Bar", which we see edge-on. It's a wall of thick dust and gas that's running diagonally across the image. The bright star near its heart is ?2 Orionis A, which is actually a triple star system.

Learning from JWST's View of Orion

Astronomers have long known that UV emissions from hot, young stars play a role in sculpting gas and dust clouds. With the NIRCam's ability to pierce through clouds of gas and dust, more details emerge about how UV light and other activities transform the clouds. "These new observations allow us to better understand how massive stars transform the gas and dust cloud where they're born," said Peeters, who is a professor of astronomy at Western University in Canada. "Massive young stars emit large quantities of ultraviolet radiation directly into the native cloud that still surrounds them, and this changes the physical shape of the cloud as well as its chemical makeup. How precisely this works, and how it affects further star and planet formation is not yet well known."

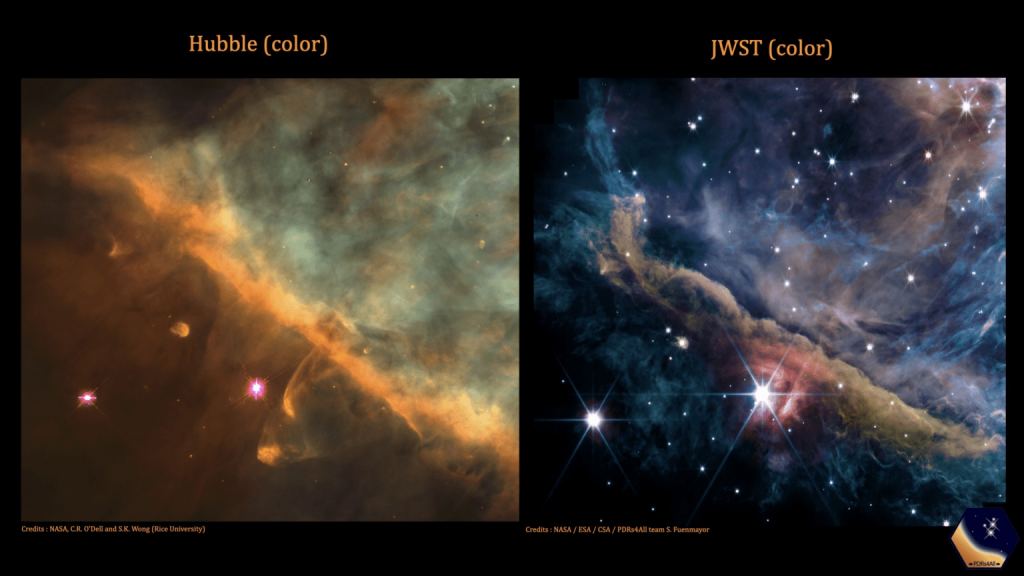

Although this nebula lies some 1,500 light-years away from us, its details offer new insight into what conditions were like in the nebula where our own Sun and planets were born. Thick clouds of gas and dust obscure the view in the Orion Nebula. This also happens in other star birth regions. Hubble and other telescopes were largely unable to "see through" the dust in these regions. JWST detects infrared light from objects hidden by the dust and "lifts the veil" on a star birth nursery to show amazing details.

"Seeing these first images of the Orion Nebula is just the beginning. The PDRs4All team is working hard to analyze the Orion data and we expect new discoveries about these early phases of the formation of stellar systems," said team member Emilie Habart. "We are excited to be part of Webb's journey of discoveries."

For More Information

Western researchers among first to capture James Webb Space Telescope images

PDRS4All

Universe Today

Universe Today