Over the course of a brief two-hour opportunity, NASA's Juno spacecraft captured a rare close look at Europa, an ice-covered moon of Jupiter that's thought to harbor a hidden ocean — and perhaps an extraterrestrial strain of marine life.

Juno has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016, but this week brought the best opportunity to look at Europa, which is the prime target for investigation by NASA's Europa Clipper probe in the 2030s. On Sept. 29, the orbiter buzzed over the moon's surface at a velocity in excess of 52,000 mph (23.6 km per second), and at an altitude of 352 kilometers (219 miles).

That's as close as any spacecraft has come to Europa since the Galileo orbiter's 218-mile flyby in 2000.

The spacecraft's JunoCam imager is designed mostly for public engagement purposes --- and over the past six years, image-processing fans have helped NASA bring stunning pictures of Jupiter to the public. Now they're doing much the same for JunoCam's photos of Europa.

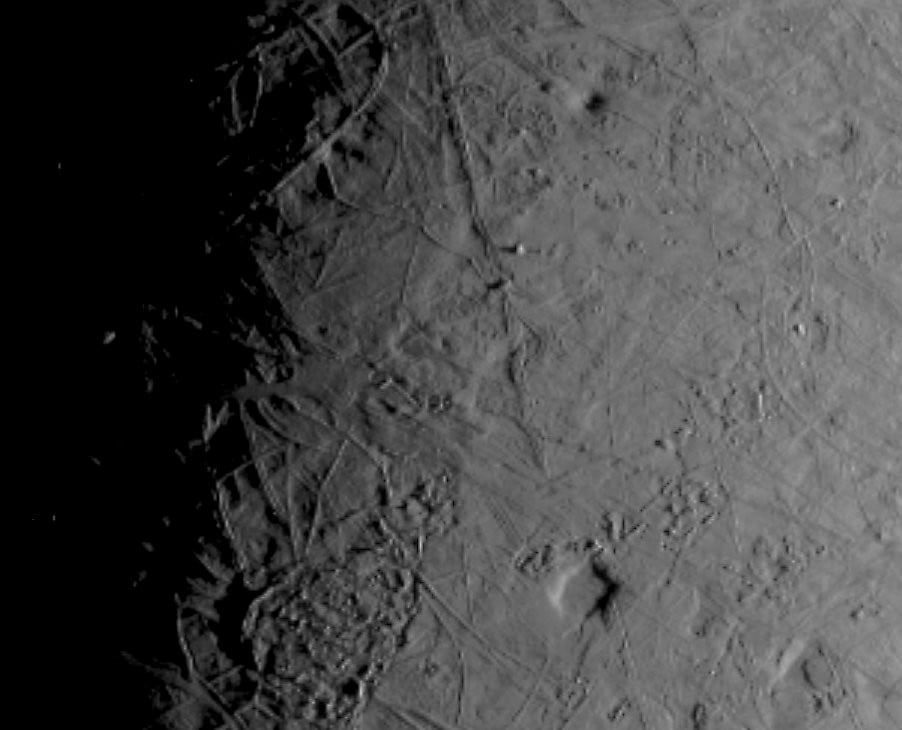

In the first image sent back by the spacecraft, focusing on an area near Europa's equator known as Annwn Regio, you can make out the trademark ridges and troughs of Europa's icy shell. The cracks in the ice are thought to be caused by the tidal forces that are generated as Europa orbits Jupiter.

Scientists expect to use JunoCam's data to produce some of the sharpest views of Europa seen to date, with a resolution of 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) per pixel. And that's not all: Other instruments captured data on Europa's ice shell structure, its surface composition, its ionosphere and the moon's interaction with Jupiter's magnetosphere.

"It's very early in the process, but by all indications Juno's flyby of Europa was a great success," principal investigator Scott Bolton, an astrophysicist at the Southwest Research Institute, said in a news release. "This first picture is just a glimpse of the remarkable new science to come from Juno's entire suite of instruments and sensors that acquired data as we skimmed over the moon's icy crust."

Candy Hansen, a mission co-investigator who's in charge of JunoCam planning at the Planetary Science Institute, said the new imagery will give scientists a better idea of what's bubbling up on Europa.

"The science team will be comparing the full set of images obtained by Juno with images from previous missions, looking to see if Europa's surface features have changed over the past two decades," Hansen said. "The JunoCam images will fill in the current geologic map, replacing existing low-resolution coverage of the area."

Those closeups --- plus readings from Juno's Microwave Radiometer --- could point to areas where Europa's surface ice is thinner, and where liquid water may exist in shallow subsurface pockets. That'll help researchers plan for the Europa Clipper mission to come.

This week's Europa encounter came a year after Juno made a close flyby of Ganymede, another ice-covered moon of Jupiter (and the largest moon in the solar system). The spacecraft is scheduled to make close flybys of Io, the most volcanically active world in the solar system, in 2023 and 2024.

Universe Today

Universe Today