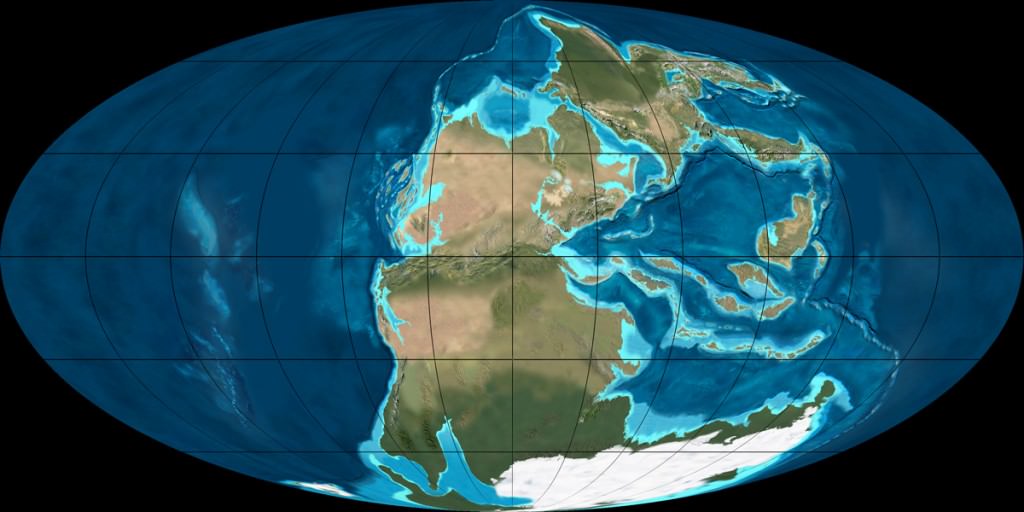

Today, the Earth’s seven continents are distributed across the surface, with North and South America occupying one hemisphere, Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia occupying the other, and Antarctica sitting alone around the South Pole. However, these continents were arranged in entirely different configurations throughout Earth’s history. On occasion, they formed supercontinents like Gondwana (ca. 550 to 180 million) and Pangaea (ca. 335 to 200 million years ago) that were surrounded by “superoceans.”

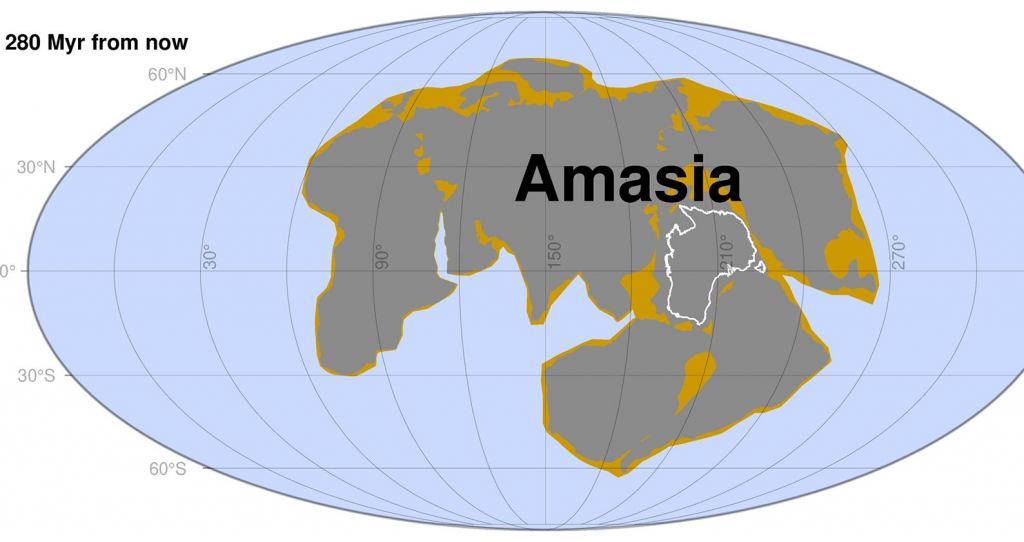

Eventually, the Earth’s tectonic plates will come together again to form the world’s next supercontinent. According to new research led by Curtin University in Bentley, Australia, this will happen roughly 200 to 300 million years from now. As they determined through a series of simulations, this will involve the Americas drifting westward until they collide with Australia and Asia (eliminating the Pacific Ocean) and Antarctica moving north to join them. This will give rise to the new supercontinent they have named “Amasia,” which will also have profound implications for life on Earth.

The research was led by Dr. Chuan Huang, a Research Fellow with Curtin University’s Earth Dynamics Research Group (EDRG) and the School of Earth and Planetary Sciences (SEPS). He was joined by John Curtin Distinguished Professor Zheng-Xiang Li of Curtin’s The Institute for Geoscience Research (TIGeR) and Nan Zhang, a professor with the Key Laboratory of Orogenic Belts and Crustal Evolution at Peking University. The paper that describes their findings, titled “Will Earth’s next supercontinent assemble through the closure of the Pacific Ocean?,” recently appeared in the National Science Review.

For the sake of their study, the research team ran a series of 4-D geodynamic modeling on a supercomputer to simulate how supercontinents form. These simulations took into account Earth-like plate tectonics and mantle convection over the course of a “supercontinent cycle,” during which the continents will separate and come together again. They found that the thickness and strength of tectonic plates under the oceans diminished as the Earth cooled over billions of years, making it difficult for the next supercontinent to form.

They also found that over the past two billion years, Earth’s continents have formed a supercontinent (aka. the supercontinent cycle) every 600 million years, which means that they are due to come together again in a few hundred million years. The new findings were significant and provided insights into what would happen to Earth in the next 200 million years. As Dr. Huang said in a Curtin University press release:

“The resulting new supercontinent has already been named Amasia because some believe that the Pacific Ocean will close (as opposed to the Atlantic and Indian oceans) when America collides with Asia. Australia is also expected to play a role in this important Earth event, first colliding with Asia and then connecting America and Asia once the Pacific Ocean closes.

“By simulating how the Earth’s tectonic plates are expected to evolve using a supercomputer, we were able to show that in less than 300 million years’ time, it is likely to be the Pacific Ocean that will close, allowing for the formation of Amasia, debunking some previous scientific theories.”

The formation of Amasia will also mean the elimination of the Pacific Ocean, which is what remains of the Panthalassa superocean that surrounded the supercontinent Pangaea. The Pacific began to form 700 million years ago as Pangaea began to break apart (making it the oldest ocean on Earth), and it has been shrinking ever since. It currently measures about 10,000 km (~6200 mi) from one end to another and is shrinking at a rate of about a few centimeters per year. In addition, the formation of the next supercontinent will dramatically alter Earth’s ecosystem and environment. As Prof. Li said:

“Earth as we know it will be drastically different when Amasia forms. The sea level is expected to be lower, and the vast interior of the supercontinent will be very arid with high daily temperature ranges. Currently, Earth consists of seven continents with widely different ecosystems and human cultures, so it would be fascinating to think what the world might look like in 200 to 300 million years’ time.”

Further Reading: Curtin University, National Science Review

I’m not convinced by this model for a few reasons. Firstly, over the last two supercontinent cycles, it’s the Atlantic (formely Iapetus) basin that has opened and shut, while the Pacific has been in existence throughout, both shrinking then regrowing, then shrinking again. Secondly, the Atlantic basin has incipient subduction zones forming west of the Mediterranean, where the Med zones have begun invading the Atlantic; and thirdly, because both the Pacific and the Indian/African regions have large up-wellings (LLSVPs) underlying them. Moreover, the Pacific ridges are bifurcating as branches subduct under the Americas. All of these factors suggest that the Pacific will maintain its spreading centers in some form, while the Atlantic will lose its.

The slow, punctuated but inexorable movement of continents towards the North since the Ediacaran, also suggests that the continents will amalgamate in the Arctic Basin, but with Australia glued to East Asia and the old Pacific spreading centers subducted. Aside from Antarctica, the Earth may then have a continental north and an oceanic south.