On September 26, 2022, leaks were discovered in the underwater Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines, located near Denmark and Sweden. Both pipelines are owned by Russia and were built to transport natural gas from Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea. Officials have said the leaks were caused by deliberate action, not accidents, and were likely intentional sabotage. While accusations have abounded, the motives behind the damage are not yet known.

Seismic disturbances in the Baltic Sea were detected, and officials said that while neither pipeline was transporting gas at the time of the blasts, they still contained pressurized methane, which is the main component of natural gas. The methane has now spewed out, producing a wide stream of bubbles on the sea surface which are visible from various satellites in Earth orbit.

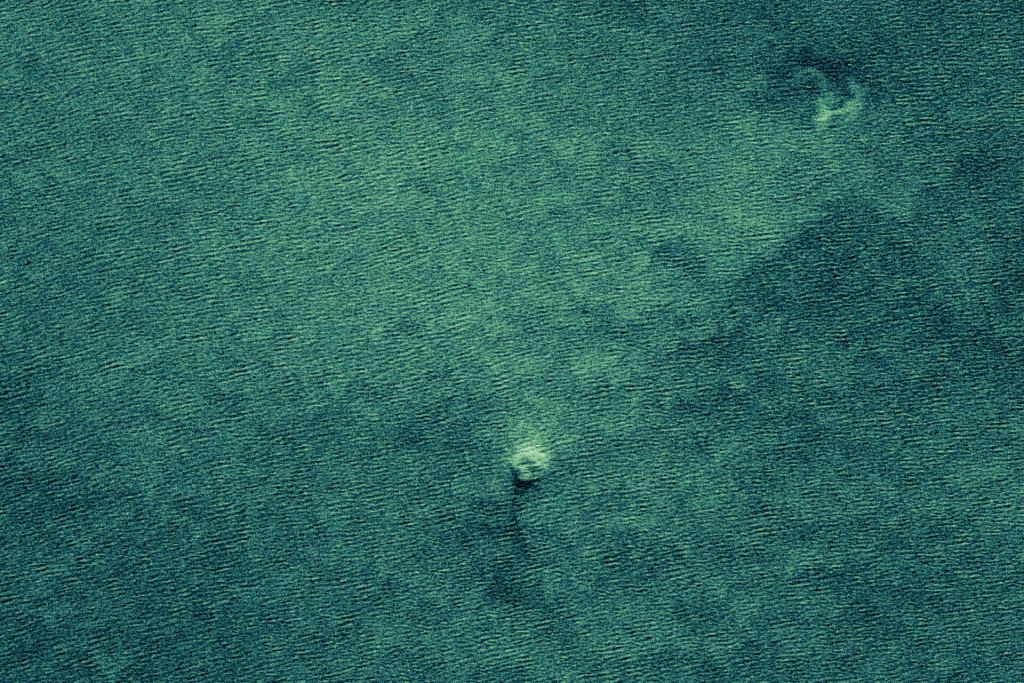

The private company GHGSat, which has active satellites monitoring methane emissions from space turned their constellation of high-resolution satellites to measure the pipeline leak. According to a European Space Agency release, GHGSat tasked its radar and microwave satellites to obtain measurements at larger viewing angles and was able to target the area where the Sun's light reflected the strongest off the sea surface – known as the 'glint spot.'

What they found is that on September 30, the estimated emission rate, as seen from its first methane concentration measurement was 79,000 kg (174,000 pounds) per hour, which makes this the largest methane leak ever detected by GHGSat from a single point-source. GHGSat said this rate is extremely high, especially considering this image comes four days following the initial breach, and this is only one of four rupture points in the pipeline. In a press release, the company said this amount of methane is equivalent to more than 90,000 kg (2 million pounds) of coal being burned in one hour.

ESA said that "monitoring methane over water is extremely difficult as water absorbs most of the sunlight in the shortwave infrared wavelengths used for methane remote sensing. This limits the amount of light reaching the sensor, thus making it extremely difficult to measure methane concentrations over the sea at high latitudes." Cloud cover contributed to the difficulty in making satellite observations of this event.

Although methane partly dissolves in water, and is not toxic, it is the second most abundant anthropogenic greenhouse gas in our atmosphere causing climate change.

"The power of active microwave radar instruments is that they can monitor the ocean surface signatures of bubbling methane through clouds over a wide swath and at a high spatial resolution overcoming one of the major limitations to optical instruments," said ESA's Scientist for Ocean and Ice, Craig Donlon. "This allows for a more complete picture of the disaster and its associated event-timing to be established."

Therefore, other Earth observation satellites carrying optical and radar imaging instruments were called upon to characterize the gas leak bubbling in the Baltic.

Planet Labs' Planet Dove satellite showed a bubbling disturbance in the Baltic Sea ranging from 500 to 700 m across the water's surface.

Other satellites saw these views of the area:

Several days later, a significant reduction in the estimated diameter of the methane disturbance was seen as the pipelines' gas emptied. This animation from the Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellite confirms this, as it shows views from September 30 and October 3, 2022.

Here's a map of the region where the pipelines are. While the leak is no longer a threat, the repercussions of this disaster remain.

Universe Today

Universe Today