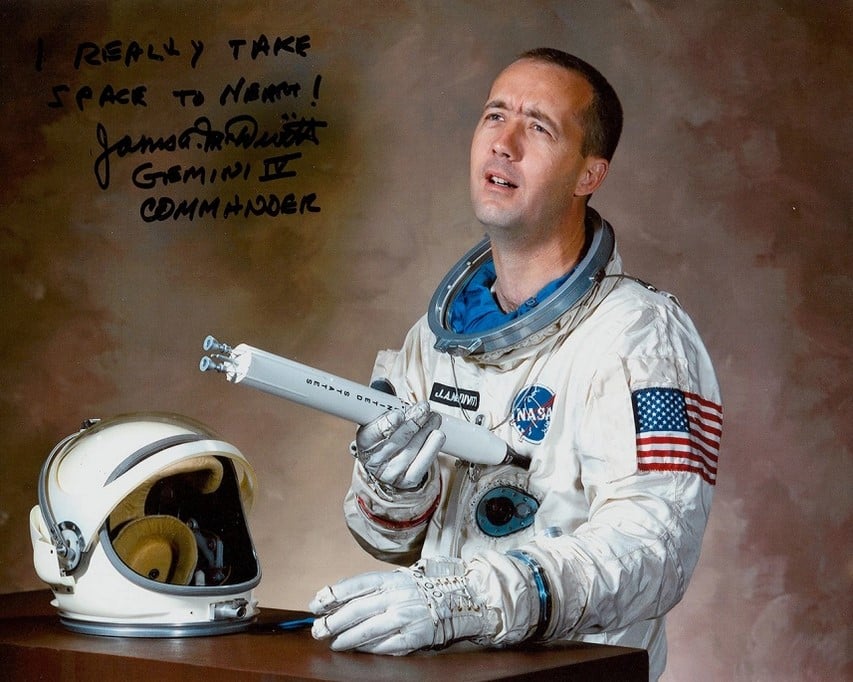

Former NASA astronaut Jim McDivitt, who commanded the important Gemini IV and Apollo 9 missions – both crucial for NASA's ability to reach the Moon -- has died at age 93. His family said he passed away peacefully in his sleep on October 13, 2022.

As an Air Force Pilot, McDivitt flew 145 combat missions during the Korean War; he then became a test pilot. He was selected as an astronaut by NASA in September 1962 as part of the second astronaut class.

McDivitt was known for his sense of teamwork and gutsy leadership, as well as his sense of humor. In an oral history interview, McDivitt recalled deciding to wait for the right moment to tell his young children he was chosen to fly on Gemini IV, the mission which included the first US spacewalk, by McDivitt's crewmate, Ed While.

"So, one Saturday morning we were sitting at our breakfast table," McDivitt recalled. "We finally got to this dramatic moment and I said, 'Kids, I'm going to tell you something really important. You know that dad's an astronaut and the astronauts fly in space. I just want to let you know that I'm going to fly in space soon.' And my older boy, Mike, who was probably seven or eight, says, 'Oh yeah, dad, I heard that at school. And then my daughter Ann said, "Oh yeah, dad, I heard that at school, too." And my son Patrick said, 'Dad, there's a fly in the milk bottle.'"

While McDivitt feelings of importance may have taken a hit that day -- thanks to his children -- his self-confidence was later apparent when asked why NASA chose him to fly two such important space flights.

"Well, I was the best-looking astronaut there was, and so they picked me on looks there," McDivitt jested. "Or maybe it was personality!"

When NASA selected McDivitt as commander of the Gemini IV mission in June 1965, he became the first-ever NASA rookie to command a mission. Gemini IV was considered NASA's most ambitious flight at the time, with White's historic spacewalk and the longest U.S. spaceflight at the time, 4 days.

While White's spacewalk is remembered for its historic nature and how White appeared to be having such a wonderful experience that he didn't want to come back inside the Gemini spacecraft, McDivitt shared a little-known story of how the spacewalk almost didn't happen because the hatch to the capsule wouldn't open initially.

"There was a handle and a bunch of little gears with teeth on them," McDivitt recalled, "and the teeth had to engage some of the other little gears. It was a fairly complex mechanism. And those gears weren't really going together properly. I said, 'Oh my God, it's not opening!'"

McDivitt said he and White decided not to tell Mission Control about it. "I mean, there was nothing they could do. They would've said, 'No,' I'm sure. Anyway, we went ahead and opened it up; and Ed went out and did his thing. And that was one of the reasons I was kind of anxious to have him get back inside the spacecraft, because I'd like to do this [close the hatch] in the daylight, not in the dark. But by the time he got back in, it was dark. So, when we went to close the hatch, it wouldn't close. It wouldn't lock. And so, in the dark I was trying to fiddle around over on the side where I couldn't see anything, trying to get my glove down in this little slot to push the gears together. And finally, we got that done and got it latched."

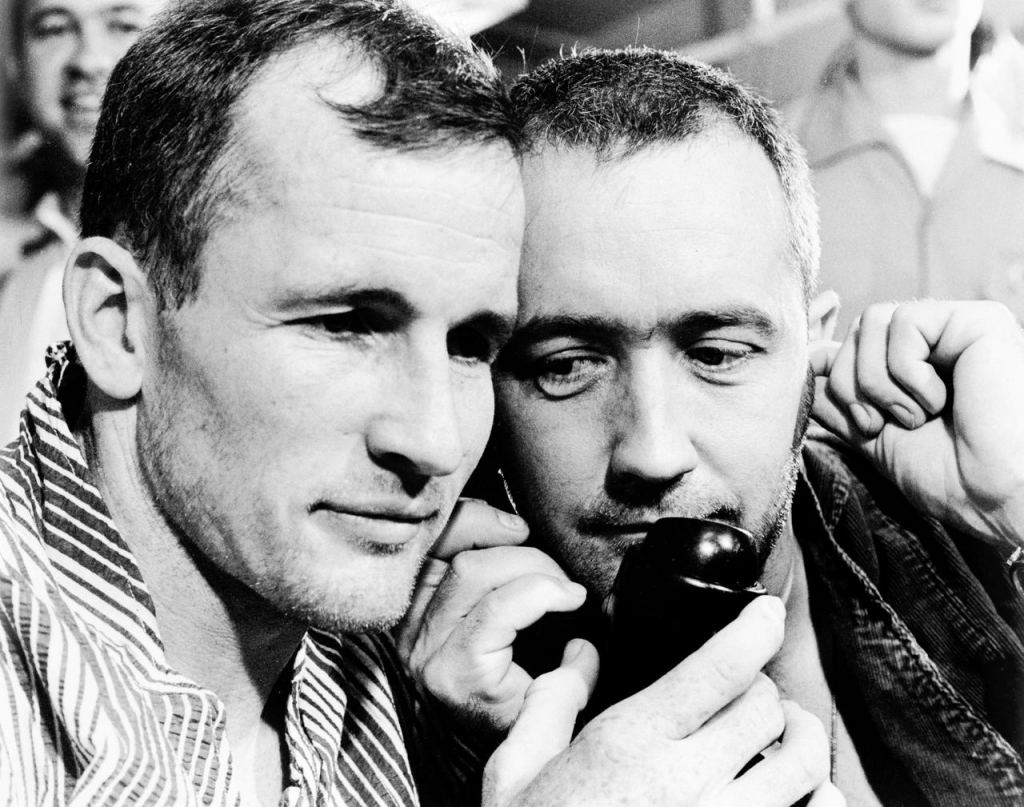

McDivitt and White had a long history, as they both attended the University of Michigan, were both in the Air Force, and had gone through the astronaut selection together. When White died tragically in the Apollo 1 fire, McDivitt said that Ed White "was the best friend I ever had."

While the Gemini missions often get overlooked in the run-up to the Apollo missions, McDivitt emphasized their importance.

"I think if it hadn't been for Gemini, flying Apollo would've been nigh on to impossible," he said. "Apollo could've been a 30-flight program with a lot of accidents if we started going to the Moon very early, if we didn't have the coordination of skills and the reliability …in the ground or the space-borne part of it. So, it was very important."

Four years later, in March of 1969, McDivitt commanded Apollo 9, which also sometimes gets overlooked as being a rather mundane flight. But it was a 10-day test flight in Earth orbit of the new lunar module, a "shakeout" first flight of the complete set of Apollo hardware that ultimately paved the way for NASA to successfully land humans on the Moon four months later in July 1969.

For Apollo 9, McDivitt was joined by Command Module Pilot David Scott and Lunar Module Pilot Rusty Schweickart. The crew spent 10 days in low Earth orbit, with the top priority of testing the LM and performing multiple dockings with the two spacecraft, the LM and Command Modules, simulating the maneuvers that would be performed during subsequent missions at the Moon. At one point, McDivitt and Schweickart flew the Lunar Module 160 kilometers (100 miles) away from the Command Module. The crew also configured the lunar module to support a spacewalk by McDivitt and Schweickart, the first EVA of the Apollo program.

But early on, the mission was in jeopardy. Schweickart's bout with space sickness in the first days of the flight caused NASA to consider bringing the crew home early and cancelling the rest of the mission.

"That would mean we might not be able to test the rendezvous and docking, meaning we might not be able to make JFK's commitment for the US to land on the Moon by the end of the decade," Schweickart told me back in 2018.

But Schweickart credits the great relationship between McDivitt and himself, where the crewmates had complete sense of trust with each other, where each of them knew innately the spacewalk was going to work, with Schweickart up to the task.

"To this day, I give Jim credit for having the incredible courage to have looked at me, to trust me, to have the relationship between us where he had confidence in his judgement and mine to make that critical of a decision," Schweickart said.

And ultimately, all went well and the mission was considered a huge success. Just before the end of Apollo 9, McDivitt called down to thank the Mission Control team for all their great work, praising the performance of the team and the spacecraft. "Might give you the impression that it might work, huh?" McDivitt joked.

But of his crewmates, McDivitt said, "We were good friends, and our lives depended on each other."

After Apollo 9, McDivitt decided to trade the challenging job of flying the Apollo missions to the equally challenging job of supervising them, and became manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office in Houston. As part of that role, it was usually his decision whether or not to continue missions after an emergency. For example, McDivitt made the recommendation to leave earth orbit after the lightning strike during Apollo 12's launch; he was involved on multiple decisions during Apollo 13 and made recommendations to continue Apollo 16 after two significant problems with the propulsion system on the Command and Service Module.

"I think it was quite fortuitous that I had a chance to fly on Apollo 9," McDivitt said later, "because the things I did on 9, which was really an engineering test flight, that stuff came into play so much more for me as the Program Manager when we were running into difficulties. So, when I had to make decisions on those later Apollo missions, it made me more confident that the decision I was making to go forward was really right."

McDivitt received numerous awards during his career, including two NASA Distinguished Service Medals and the NASA Exceptional Service Medal. For his service in the U.S. Air Force, he also was awarded two Air Force Distinguished Service Medals, four Distinguished Flying Crosses, five Air Medals, and U.S. Air Force Astronaut Wings. McDivitt also received the Chong Moo Medal from South Korea, the U.S. Air Force Systems Command Aerospace Primus Award, the Arnold Air Society JFK Trophy, the Sword of Loyola, and the Michigan Wolverine Frontiersman Award.

McDivitt's passing leaves the Apollo 8 crew as the last Apollo crew with all crew members still living.

Universe Today

Universe Today