It’s winter here on Earth, for those living in the northern hemisphere. This means snow, rain, colder temperatures, and all the other things we associate with “the festive season.” Much the same is true for Mars (aka. “Earth’s Twin”), which is also experiencing winter in its northern hemisphere right now. This means colder temperatures, especially around the polar regions where it can get as low as -123 °C (-190 °F), as well as ice, snow, frost, and the expansion of the polar ice caps – which are composed of both water ice and frozen carbon dioxide (“dry ice”).

While Mars does not experience snowfall the same way Earth does, seasonal change results in some very interesting phenomena. Thanks to the many robotic explorers NASA and other space agencies have sent to Mars in the past fifty years, scientists have been able to get a close-up look at these phenomena. These include the Viking orbiters and landers that studied the planet in the 1970s (with groundbreaking results) to the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), the Mars Exploration Rovers (Spirit and Opportunity), and the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers exploring the surface today.

Thanks to these dedicated orbiters, landers, and rovers, scientists have learned a few salient facts about snow on Mars: it comes in two varieties (water ice and dry ice), and it only ever snows in the coldest regions and times – at the poles, under cloud cover, and at night. Because Mars’ atmosphere is so thin and its temperatures so extreme, water and carbon dioxide do not freeze but sublimate, transforming from a gas directly to ice (and back again). On top of that, dry ice snowflakes are cubic, meaning they have four sides instead of the familiar six-sided configuration we are familiar with.

As with water molecules, this is because a crystal’s shape depends on how atoms arrange themselves. In the case of CO2, molecules always bond in groups of four. Moreover, snow never reaches the ground on Mars but sublimates as it falls from the clouds to the surface. Since most orbiters cannot see through these clouds, and rovers cannot withstand the extreme cold, no images of falling snow have ever been taken. But scientists know that Mars experiences snowfall, thanks to a handful of dedicated instruments.

These include the Mars Climate Sounder (MCS) aboard the MRO, which observes the Martian atmosphere in visible and infrared light to measure the temperature, humidity, and dust content of the Martian atmosphere. This allows science teams to peer through cloud cover and detect CO2 snow falling to the ground. Sylvain Piqueux, a planetary research Scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, explained the intricacies of Martian snow in a recent interview with NASA’s Mars News Report (a series dedicated to educating the public on the exploration and study of the Red Planet). As he explained:

“Enough falls that you could snowshoe across it. If you were looking for skiing, though, you’d have to go into a crater or cliffside, where snow could build up on a sloped surface. Because carbon dioxide ice has a symmetry of four, we know dry-ice snowflakes would be cube-shaped. Thanks to the Mars Climate Sounder, we can tell these snowflakes would be smaller than the width of a human hair.”

In addition, NASA’s Phoenix mission landed within 1,000 miles (about 1,600 kilometers) of Mars’ north pole in 2008. As part of its science operations, the lander used a laser-based atmospheric sensor – part of a special meteorological station provided by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) – to detect water ice snow falling to the surface. The Viking landers also detected water frost at their landing sites, and NASA’s Odyssey orbiter observed frost forming and sublimating at sunrise many times during its mission.

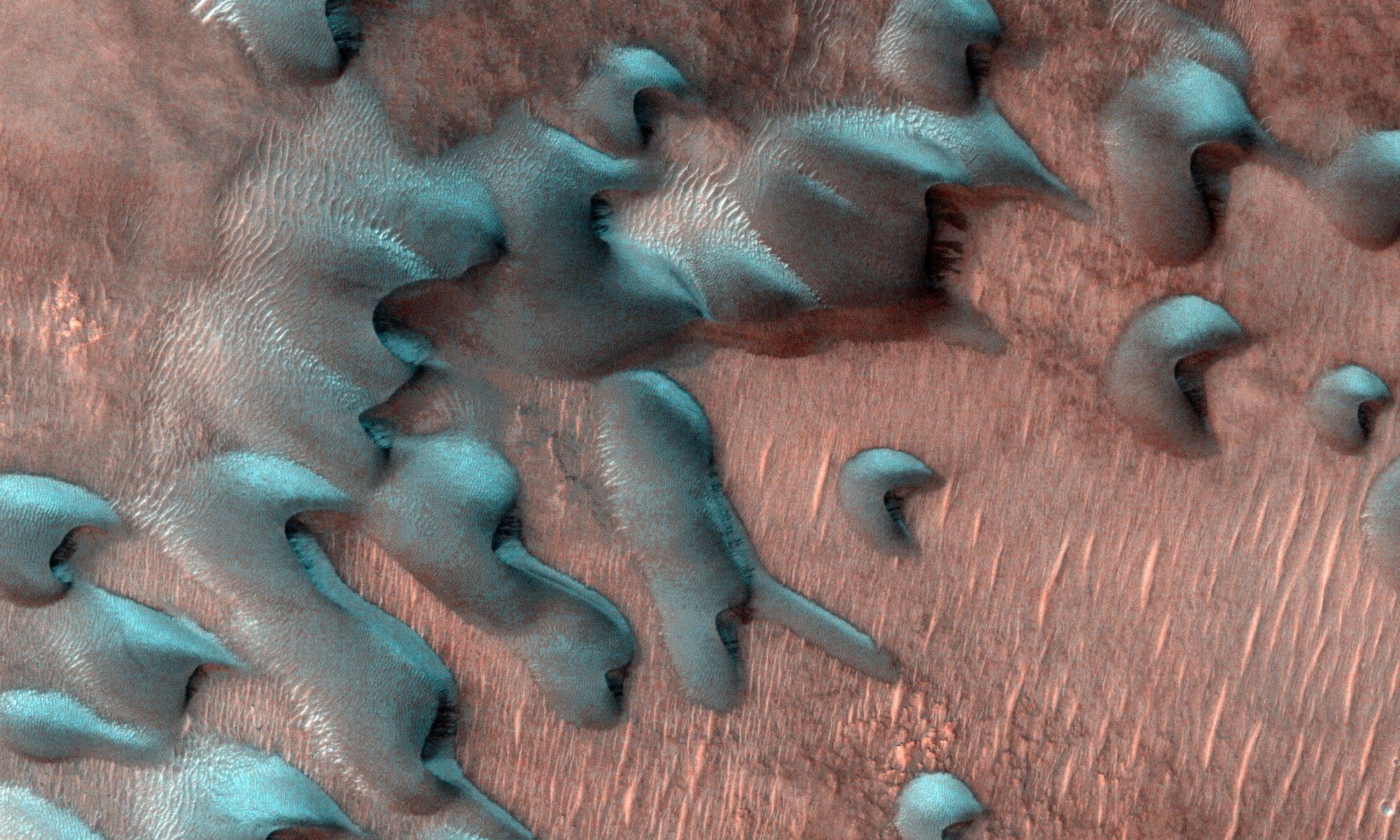

When the CO2 ice sublimates near the end of winter, the most iconic surface features on Mars result. This includes the strange and beautiful shapes that scientists have nicknamed “spiders,” “Dalmatian spots,” “fried eggs,” and “Swiss cheese.” The “spring thaw” also causes geysers to erupt as sunlight passes through layers of translucent ice, heating the gas pockets beneath it. This triggers eruptions that send dust onto the surface, creating a feature known as “Spring Fans” that scientists are studying to learn more about which direction the Martian winds are blowing.

As Piqueux explained, all of this data will be vital when it comes time to send crewed missions to Mars, which NASA hopes to do by the 2030s:

“[T]he Pheonix lander, the NASA mission that arrived on Mars in 2008, observed beautiful frost landscapes that formed around it. The Pheonix lander was also able to scratch the surface and, for the first time, see this water ice just below the ground. This is the kind of water ice that astronauts could potentially use in the future when we go there.”

Many fascinating things accompany seasonal changes on Mars, and we are fortunate to bear witness to these things thanks to many generations of robotic missions. Soon enough, astronauts will witness Mars and its dynamic climate firsthand, and their research will fuel scientific breakthroughs and discoveries for generations to come!

Further Reading: NASA