Since last summer, Jupiter’s third largest moon, Io, has been lighting up the Jovian system with a major burst of volcanic activity. As the Solar System’s most volcanically active world, Io is no stranger to such outbursts, but this year’s display has been unusually energetic.

Researcher Jeff Morgenthaler, who has been observing Io’s volcanism since 2017, says this is the largest volcanic outburst he’s seen yet. Morgenthaler’s observations are taken with the Planetary Science Institute’s small-scale Io Input/Output observatory (IoIO).

Io goes through phases of volcanic activity on an almost yearly basis. The eccentricity of its orbit and close proximity to the strong gravity of Jupiter causes the moon to bulge and compress continuously, adding energy to the world in a process known as tidal heating. This same process is responsible for the liquid subsurface oceans within nearby moon Europa – but Io is closer to its planet and has a rockier composition, resulting in extensive lava flows, eruptions, and violent crust upheavals.

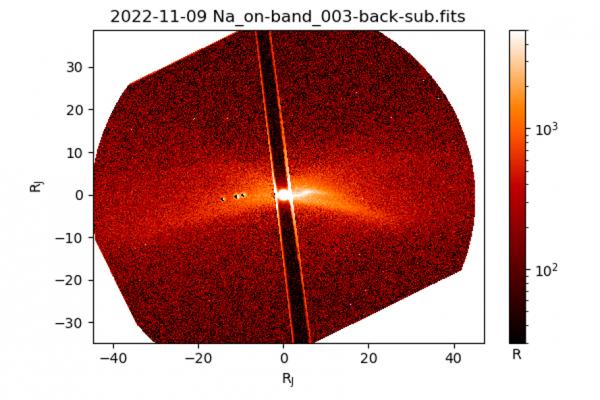

These extreme volcanic conditions affect more than just the moon’s surface. Io surface gravity is low enough (just slightly stronger than the gravity on Earth’s moon) that some of the gasses and light materials from Io’s volcanoes can escape into orbit around Jupiter. Largely consisting of ionized sulfur, this material forms a donut-shaped ring around Jupiter known as the Io plasma torus.

Usually, the torus brightens at the same time that Io experiences a burst of eruptions. However, that was not the case with the most recent burst of volcanism, which lasted from September to December 2022.

Morgenthaler proposes a couple of possible explanations:

“This could be telling us something about the composition of the volcanic activity that produced the outburst or it could be telling us that the torus is more efficient at ridding itself of material when more material is thrown into it.”

To know for sure, we’d need measurements of the region in-situ. Luckily, NASA’s Juno probe passed through the area in mid-December, coming within 64,000 km of Io on December 14th. Juno has instruments on board capable of characterizing the radiation environment within the torus, and Morgenthaler hopes that data from the flyby will reveal whether there was something different about the composition of this outburst as compared to previous ones. Juno’s Io flyby data is still being downloaded and processed.

Juno is expected to pass even closer to Io next December, coming within 1,500 km of the moon, the closest a spacecraft has been to Io since the Galileo mission in 2002.

Morgenthaler will be observing Io and its plasma torus with IoIO then, too, as long as cloudy weather doesn’t get in the way.

IoIO is a small telescope, and from Earth, it can only see the torus by filtering out light from Jupiter, which is bright enough that it would normally drown out the comparatively dim torus. IoIO uses a coronagraph to ensure that the telescope isn’t blinded by the gas giant’s glow.

“One of the exciting things about these observations is that they can be reproduced by almost any small college or ambitious amateur astronomer,” says Morgenthaler. “Almost all of the parts used to build IoIO are available at a high-end camera shop or telescope store.”

IoIO consists of a 35 cm (14 Inch) Celestron Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope, modified with a custom-built coronagraph.

Learn More:

“PSI’s Io Input/Output observatory discovers large volcanic outburst on Jupiter’s moon Io.” Planetary Science Institute.

Featured Image: IoIO image of Io’s sodium nebula in an outburst. Credit: Jeff Morgenthaler, PSI.