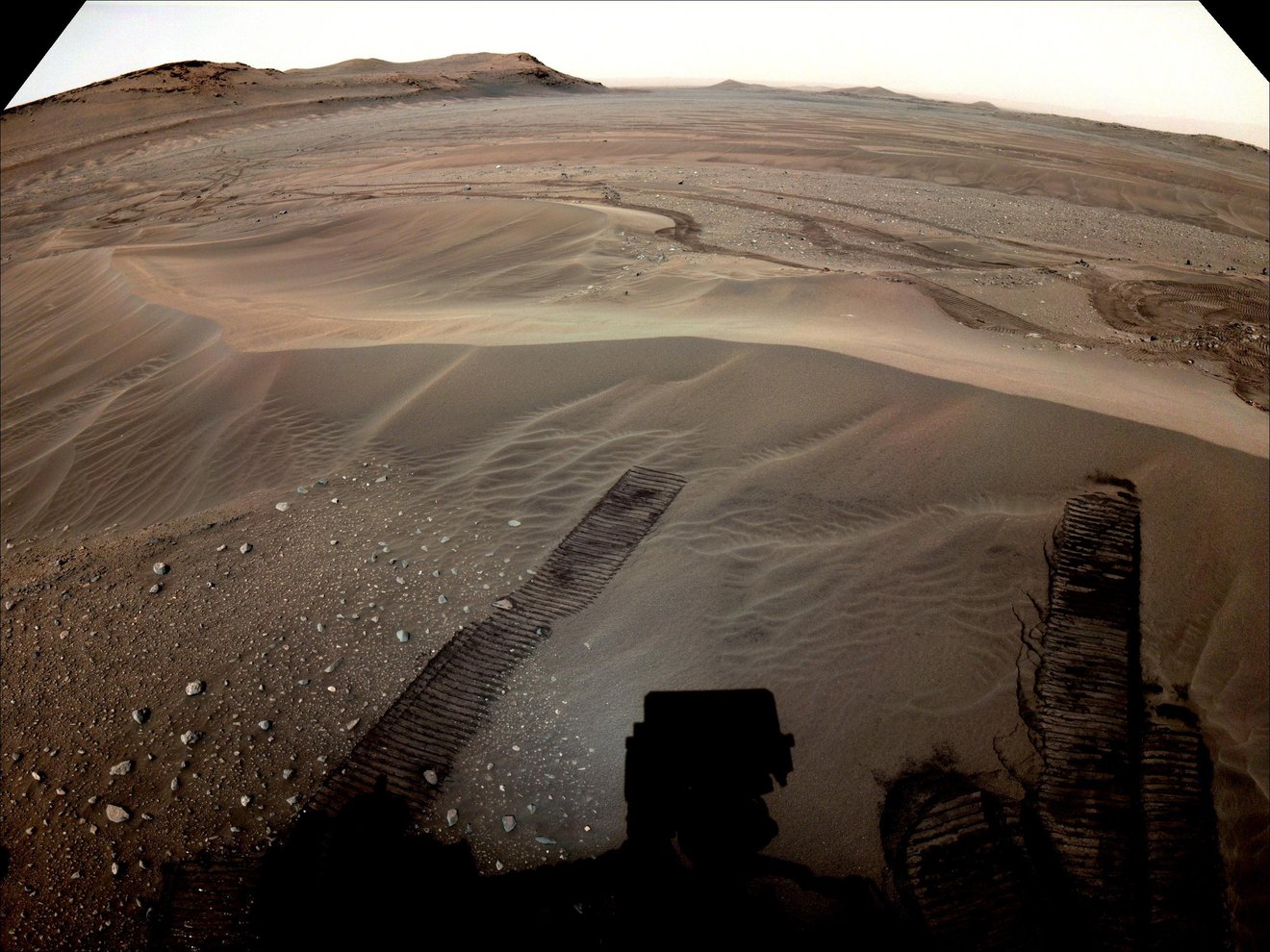

At this point in its mission, NASA’s Mars Perseverance Rover has collected almost 50% of its samples. The rover is now building its first sample ‘depot’ on the surface of Mars. The depot is a flat, obstacle-free area with 11 separate landing circles, one for each sample tube and one for the lander.

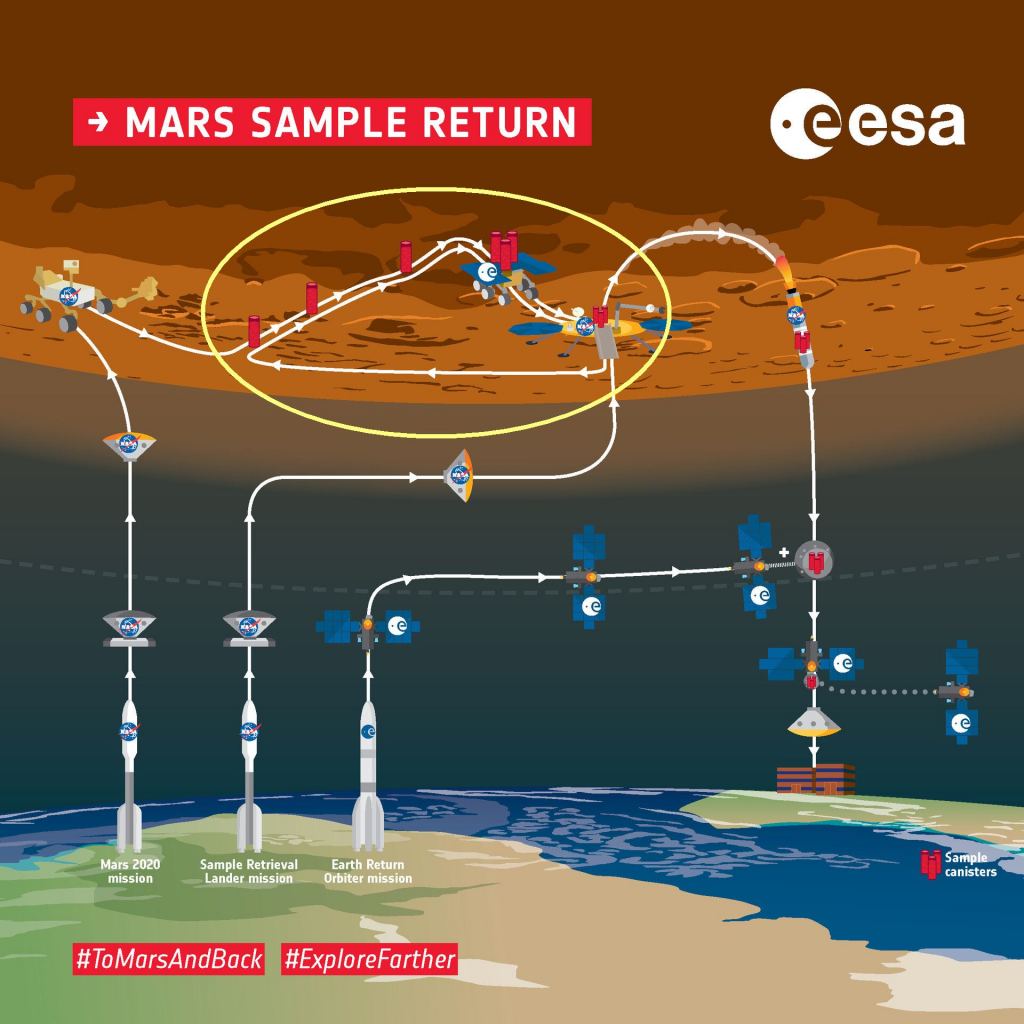

A future mission will retrieve these samples by helicopter.

Studying samples from Mars will be a peak moment for eager planetary scientists. Even with all we’ve learned from orbiters, landers, and rovers, having Martian samples in full-featured Earth labs will enable comprehensive study that simply isn’t possible with robotics, even with Perseverance’s suite of advanced instruments.

There’s still a long time until the Perseverance rover’s samples are returned to Earth in 2033, but the rover is collecting samples and starting to cache them in a depot. Perseverance has collected 18 of 38 samples or 47%. The bulk of them are rock core samples, but there are regolith and atmospheric samples as well.

Placing the samples on the surface is a detailed process. The tubes aren’t simply left on the ground. Since they’ll be retrieved by helicopters at a later date, they have to be positioned so that the helicopters can access them one at a time. That means the entire depot area must contain 11 separate landing spots.

Complicated operations like this need to be planned out precisely, and without adequate maneuvering room, the whole endeavour can become much more complicated than it needs to be and can even risk failure.

It’s even more critical when the site is on another planet.

“Up to now, Mars missions required just one good landing zone; we need 11,” said Richard Cook, Mars Sample Return program manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “The first one is for the Sample Retrieval Lander, but then we need 10 more in the vicinity for our Sample Recovery Helicopters to perform takeoffs and landings, and driving too.”

“You can’t simply drop them in a big pile because the recovery helicopters are designed to interact with only one tube at a time,” said Cook.

Perseverance collects duplicate samples from each of its sampling locations. One of each sample will be placed in a surface depot as backup, and one will be kept inside Perseverance. NASA and the ESA have refined the Mars Sample Return mission architecture over time. Formerly, the plan included a fetch rover to collect the samples and a Sample Return Lander. But with the success of the Ingenuity Helicopter, that plan has changed.

The Sample Return mission will still include a Sample Return Lander, but instead of a fetch rover, two helicopters will collect the samples. But the helicopters and the depot samples are just a backup plan. NASA and the ESA now plan for Perseverance itself to deliver the samples to the Sample Return Lander, where a small rocket will launch the samples into orbit. There they’ll be retrieved by another spacecraft, the Earth Return Orbiter, that will send them back to Earth.

Sample return is still a long way off, but selecting a depot and positioning samples is another milestone on the journey toward that rewarding day in 2033. The depot site is named Three Forks, and once the full set of samples is collected, the samples at Three Forks will mirror the samples inside Perseverance.

“The samples for this depot – and the duplicates held aboard Perseverance – are an incredible set representative of the area explored during the prime mission,” said Meenakshi Wadhwa, the Mars Sample Return program principal scientist from Arizona State University. “We not only have igneous and sedimentary rocks that record at least two and possibly four or even more distinct styles of aqueous alteration, but also regolith, atmosphere, and a witness tube.”

The complexity of the Sample Return mission is fascinating in itself. It involves multiple launches from Earth, a surface rover and a surface lander, helicopters, an ascent vehicle and an orbiting Earth return vehicle. In a way, it’s a celebration of human ingenuity.

But in the final analysis, it’s all about the samples and what they will tell us about Mars.

Mars is a puzzle that defies completion. It’s remarkable that we’ve learned as much as we have about the planet. But the missing piece is a set of samples from the planet that scientists can study on Earth.

Before Perseverance was launched, a lot of work went into planning its samples. These first samples are from the Jezero Crater floor. They form a suite of samples from what are called the Séítah formation and the Máaz formation.

Scientists think that the Séítah geological unit is similar to places on Earth where volcanic flows meet the ocean, like at Hawaii or Iceland. Séítah’s igneous rocks likely formed when thick underground lava or a magma chamber cooled down. Jezero Crater is an ancient paleolake, so eventually, this lava came into contact with water that filtered down through the cracks created by whatever impacted Mars and created the crater. That might have led to conditions that supported life.

Séítah contains a common mineral called olivine, a mineral that reacts more quickly with water than other minerals typically found with it. And Perseverance has already shown us that the olivine was only slightly altered by water in at least two phases of exposure. This means the water probably slowly percolated through the Jezero crater’s floor. During each of the olivine’s exposure to water, the water that migrated through cracks and fissures in the rock could have supported life. The activity would’ve also formed new minerals, and those minerals could hold evidence of ancient life if it existed.

The multi-hued map on the right shows the diversity of igneous (solidified from lava or magma) minerals in the same region. Olivine is shown in red. Calcium-poor pyroxene in green. Calcium-rich pyroxene is in blue. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/CRISM/CTX/HRSC/MSSS/USGS

But Perseverance also found some unhelpful chemicals called perchlorates. They’re rare on Earth and are toxic to life. They contraindicate life at Jezero Crater, but not entirely. There’s lots left to untangle.

This is why the samples are so important. Perseverance is a remarkable machine, but it has its limitations. Only by getting these samples back to Earth and performing more rigorous investigations than Perseverance is capable of can we hope to find deeper answers to Mars’ past. Maybe then we can confirm whether microbes lived there or not.

Perseverance’s Prime Mission ends today, January 6th. So far, Perseverance has collected about half of its samples. Once it’s finished depositing samples at the Three Forks Depot, it’ll head to the top of the nearby delta in its next science phase, which the Perseverance team calls the Delta Top Campaign.

Sometime in February, Perseverance will ascend the steep embankment to the top of the nearby delta. The samples from Delta Top will be different from the crater floor samples.

Perseverance’s reach is limited, but it can extend it by travelling to the top of the delta. There, ancient flowing water deposited boulders and rocks from elsewhere on Mars. By sampling this region, scientists can gather a more diverse collection of samples than is possible on the floor of Jezero Crater.

“The Delta Top Campaign is our opportunity to get a glimpse at the geological process beyond the walls of Jezero Crater,” said JPL’s Katie Stack Morgan, deputy project scientist for Perseverance. “Billions of years ago, a raging river carried debris and boulders from miles beyond the walls of Jezero. We are going to explore these ancient river deposits and obtain samples from their long-travelled boulders and rocks.”

The delta was created by an ancient river that flowed into Jezero Crater. The river channel is called Neretva Vallis, and the river that flowed through it last flowed about 3 billion years ago. That river created the sediment delta that Perseverance will explore next. The rocks in this region will hold more clues to Mars.

When the Apollo missions brought lunar samples to Earth, it energized the study of the Moon. Those samples are still being studied. In fact, a sample from Apollo 17 was opened for the first time in March 2022. Another Apollo 17 sample was opened for the first time in 2019. As forecast by scientists in the 1970s, research methods and technologies have advanced enormously since the samples were gathered. These ones were held in reserve in anticipation of those advances, and an entirely new generation of scientists has the responsibility of studying those samples.

The Mars samples could follow a similar trajectory. We don’t know exactly what we’ll learn from the Mars samples. We don’t know if they’ll hold evidence that confirms Mars’ ancient habitability. We don’t know for sure what we’ll learn from them when we first get them or what secrets might be revealed only after decades of additional scrutiny.

But one way or another, they’re pieces of the Mars puzzle, and they’ll advance our understanding in ways that may be surprising.