While astronomers and engineers were trying to calibrate one of the James Webb Space Telescope’s instruments last summer, they serendipitously found a previously unknown small 100–200-meter (300-600 ft) asteroid in the main asteroid belt. Originally, the astronomers deemed the calibrations as a failed attempt because of technical glitches. But they noticed the asteroid while going through their data from the Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI), and ended up finding what is likely the smallest object observed to date by JWST. It is also one of the smallest objects ever detected in our Solar System’s main belt of asteroids.

“We — completely unexpectedly — detected a small asteroid in publicly available MIRI calibration observations,” explained Thomas Müller, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany, in a press release. “The measurements are some of the first MIRI measurements targeting the ecliptic plane and our work suggests that many, new objects will be detected with this instrument.”

The asteroid is not yet named, as follow-up observations need to be done to confirm the discovery. Additionally, more observations will be done to better characterize this object’s nature and properties.

This finding was unexpected because astronomers weren’t sure JWST had the capability find asteroids this small. But this detection showed otherwise.

What’s more, based on this finding, astronomers suspect that even short MIRI observations close to the plane of the Solar System will always include a few asteroids, most of which will be unknown objects. This is reminiscent of the early calibration images in March of 2022 where previously unseen background galaxies were showing up everywhere. Jane Rigby, JWST operations project scientist said, “Basically, everywhere ever we look, it’s a Deep Field.”

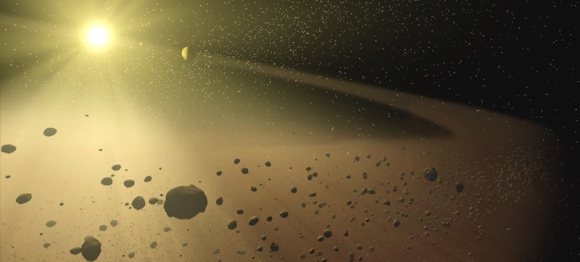

So, JWST’s infrared capabilities should be a boon to detecting some of the hardest to find asteroids. Scientists estimate the asteroid belt has between 1.1 and 1.9 million asteroids larger than 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) in diameter, and millions of smaller ones. Most of the undiscovered asteroids are the smaller ones (less than 100 km across) which are more difficult to detect.

“This is a fantastic result which highlights the capabilities of MIRI to serendipitously detect a previously undetectable size of asteroid in the main belt,” said Bryan Holler, Webb support scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute. “Repeats of these observations are in the process of being scheduled, and we are fully expecting new asteroid interlopers in those images!”

The calibrations being performed while JWST was targeting another main-belt asteroid (10920) 1998 BC1, which astronomers discovered in 1998. The calibration team considered them to have failed for technical reasons due to the brightness of the target and an offset telescope pointing.

However, even the failure was a success in another way, because the team was able to test a new technique to constrain an object’s orbit and to estimate its size. The validity of the method was demonstrated for asteroid 10920 using the MIRI observations combined with data from ground-based telescopes and ESA’s Gaia mission.

“Our results show that even ‘failed’ Webb observations can be scientifically useful, if you have the right mindset and a little bit of luck,” said Müller. “Our detection lies in the main asteroid belt, but Webb’s incredible sensitivity made it possible to see this roughly 100-metre object at a distance of more than 100 million kilometers.”