Technological revolutions can bring about dramatic changes in various fields, some of which are only tangentially related to the field being disrupted. Occasionally, a few technological revolutions happen simultaneously, enabling concepts that would have been impossible without any of them. Such revolutions are currently happening in the space industry. With rockets more massive than ever coming online, and mega-constellations of satellites roaming our skies, there is plenty of disruption going on. Now a team from MIT hopes to use those technologies to look at an area of astronomy that has never been seen before – low-frequency radio astronomy.

Giant radio telescopes, such as the now-defunct Arecibo, have one major disadvantage – they are located on Earth. Our ionosphere neatly blocks the very low-frequency radio spectrum, from frequencies of 100 kHz to around 15 MHz. So while those massive telescopes are theoretically capable of detecting those signals, none of them make it through the ionosphere for them to detect.

Alternatively, telescopes in space would be perfectly capable of detecting these low frequencies. But they would have to be absolutely massive to do so – on the order of hundreds of meters in diameter, which is currently far beyond the capability of even the most powerful rockets proposed. So far, building a radio telescope for detecting low-frequency signals in space has been a non-starter.

But there may be an alternative. Newer radio telescopes, such as MeerKAT, use a technique called interferometry. Instead of requiring one colossal telescope, interferometry telescopes use a series of small ones bound together by the laws of physics and mathematics to detect low-frequency radio waves that would usually be seen only by giant detectors.

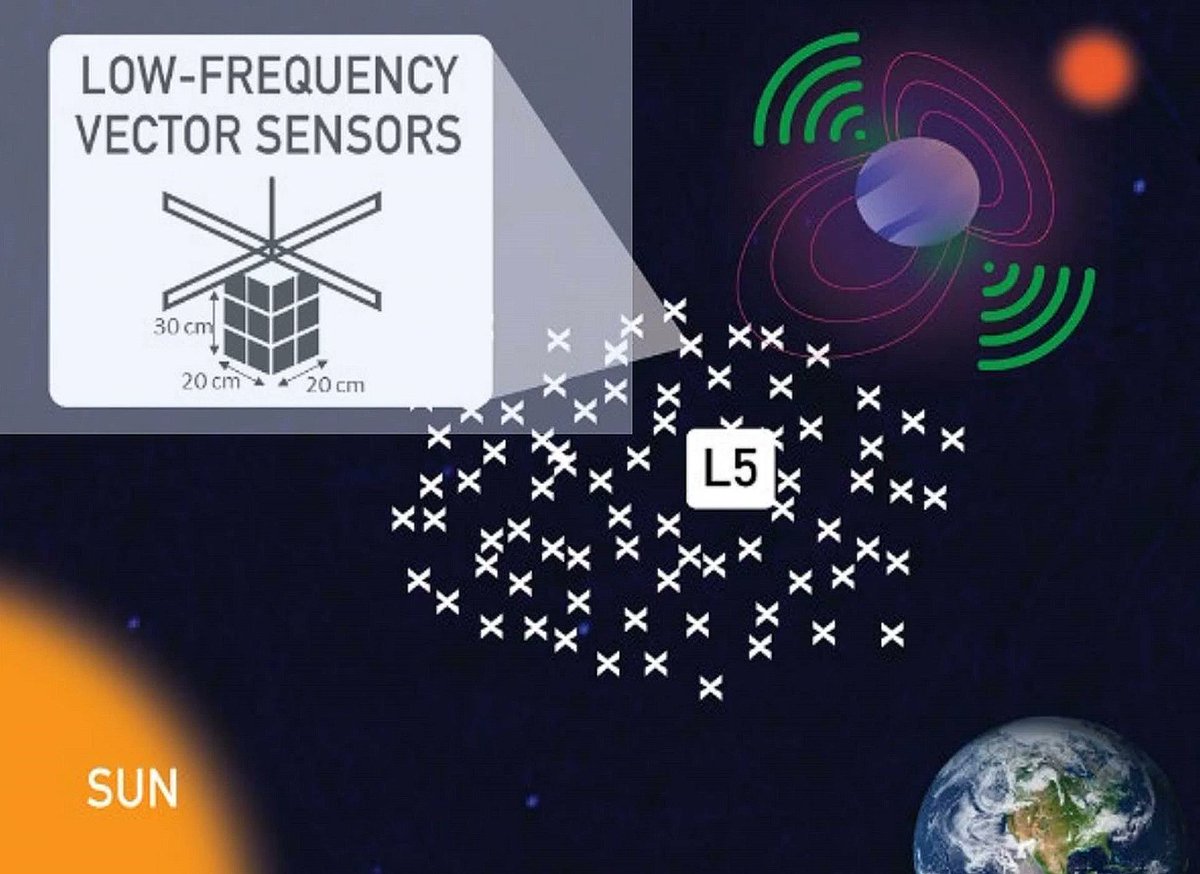

What Mary Krupp and her team at MIT have suggested seems like a logical next step – why not build an interferometric telescope in space? Their project, known as the Great Observatory for Long Wavelengths, or, since astronomers are so fond of acronyms, Go-LoW, was recently funded by NASA’s Institute for Advanced Concepts, and its premise is relatively simple.

Take an interferometric system similar to MeerKAT and launch it to the L5 Lagrange point. The idea takes ideas from a few current technological advances and combines them. The first would be how to make hundreds of thousands of satellites inexpensively.

Credit – CreamerMedia YouTube Channel

For that, they rely on the technologies developed by SpaceX for their Starlink mega constellation. Its 40000+ planned satellites have significantly decreased the cost of small satellite components, making it economically feasible to build that many satellites without breaking the bank.

The second technological development is the advent of heavy-launch rockets. With the power of Starship or the SLS, thousands of satellites can be launched to Earth-Sun L5 Lagrange point about 1.5 million kilometers away. While it might not necessarily be cheap to do so, it certainly wouldn’t be as expensive as it had been in past generations.

Now seems like an ideal time for such an idea, though NIAC is known for backing projects in the very early stages. The MIT team will work on conceptual aspects of the mission in this Phase I grant, which lasts for nine months. Ultimately, they hope to have a road map to making the project a reality in the next 10-20 years. They might just be able to catch that technological wave at the right time and change our understanding of radio astronomy forever.

Learn More:

NASA / MIT – Great Observatory for Long Wavelengths (GO-LoW)

UT – LOFAR sees Strange Radio Signals Hinting at Hidden Exoplanets

UT – New Radio Telescope to Help SETI Scan Unexplored Frequencies for Extraterrestrials

Science Alert – Astronomers Have Detected an Intense And Mysteriously Low Frequency Radio Signal Coming From Space

Lead Image:

Artist depiction of the GoLOW swarm.

Credit – Mary Knapp / MIT / NASA