Astronomy is poised for another leap. In the next several years, major ground-based telescopes will come online, including the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT,) the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT,) the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT,) and the Vera Rubin Observatory. The combined power of these telescopes will help drive discovery in the next couple of decades.

But something threatens to undermine astronomical observing in the coming years: Starlink and other internet satellite constellations.

Now a group of astronomers have shown that even the Hubble can't escape the satellite problem.

Since the launch of Starlink and other communication satellite constellations, there's been a growing recognition of their negative effect on astronomy. The international astronomy community has pointed out how the growing number of internet satellites in Earth orbit is complicating astronomical observations by ground-based telescopes. Now their concern is spreading to the Hubble.

"With the growing number of artificial satellites currently planned, the fraction of Hubble Space Telescope images crossed by satellites will increase in the next decade and will need further close study and monitoring."From "The impact of satellite trails on Hubble Space Telescope observations."

A new research letter in Nature Astronomy shows the effect that satellites are having on astronomical observations by Hubble in Low-Earth Orbit. The study is " The impact of satellite trails on Hubble Space Telescope observations. " The lead author is Sandor Kruk, a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics.

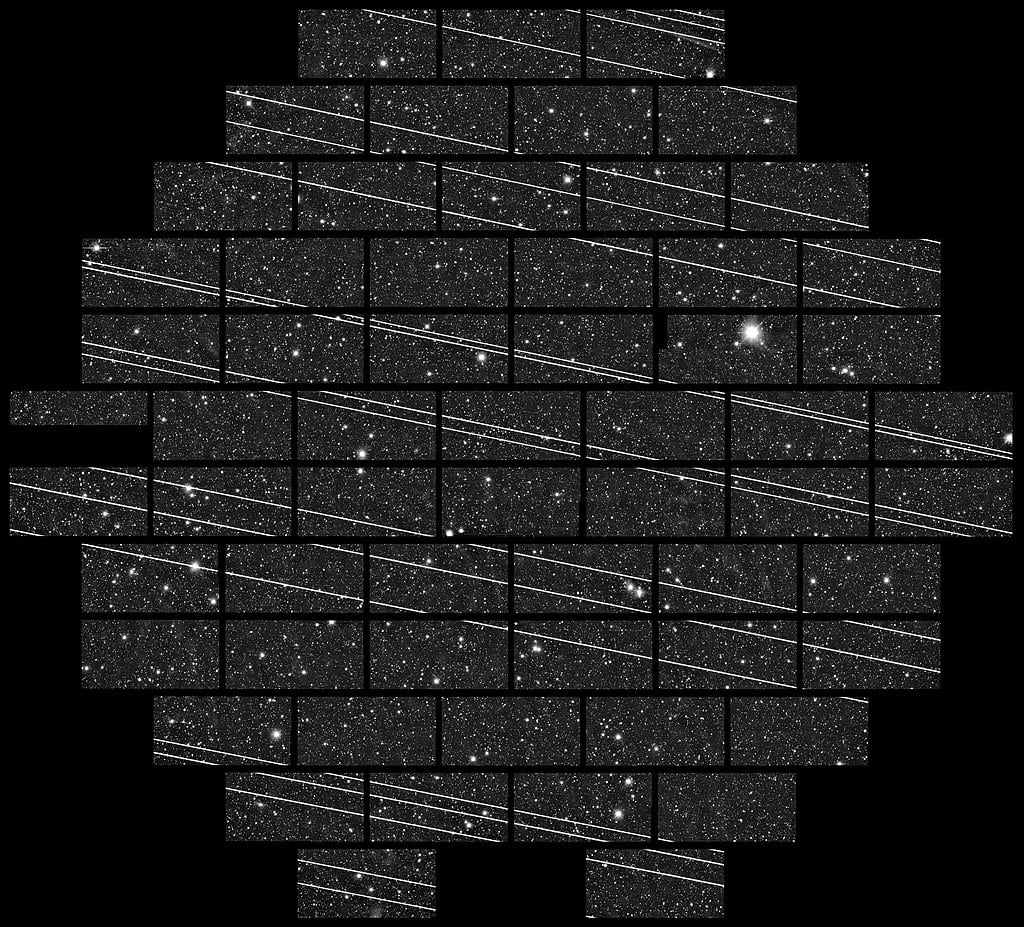

The authors examined 20 years of Hubble images using citizen science volunteers and machine learning. Their research showed that 2.7% of Hubble images during that time contained satellite trails. To no one's surprise, the number of satellite trails in the images is increasing over time as more and more satellites are lofted into orbit. The typical exposure time for Hubble images is 11 minutes, increasing the likelihood of satellite trails.

"With the growing number of artificial satellites currently planned, the fraction of Hubble Space Telescope images crossed by satellites will increase in the next decade and will need further close study and monitoring," the authors write.

Astronomers were concerned about this as far back as 1986, several years before Hubble launched and before internet satellite constellations were dreamed of. In a paper titled " Artificial Earth Satellites Crossing The Fields Of View Of, And Colliding With, Orbiting Space Telescopes," the authors wrote that artificial Earth satellites "... will cross the field of view of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) with significant frequencies and brightnesses." In 1986 alone, another 136 satellites were placed in orbit.

The Hubble's orbit is slowly decaying due to drag. It was placed in orbit in 1990 at 547 kilometres or 340 miles above Earth. Since then, it's decayed down to about 538 kilometres or 333 miles. As it decays, the telescope is sensitive to a larger number of satellites above it. Its sensitivity depends on things like solar illumination angle, position and telescope pointing.

The effect on Hubble images is obvious.

Hubble doesn't take quick snapshots. Its Fine Guidance Sensors (FGS) allow it to take pinpoint time exposures, a necessity for observing faint and distant objects in space. One of Hubble's most famous images, the Hubble Extreme Deep Field, took 22 days of observing time. That's extreme, but the telescope routinely takes stacked composite images that require 35-minute exposures. That increases the effect that satellites have on the Hubble's observations.

The researchers found 144 Hubble images containing multiple satellite trails. 133 of them contained two trails, ten contained three, and one contained four trails.

With all of the data in hand, the team calculated the chance of seeing a satellite trail in any single Hubble image since 2009. For the following graph, an exposure time of 11.2 minutes is used. The two image groups are for the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS)/Wide Field Camera (WFC) and the Wide Field Camera 3 Ultraviolet channel. The odds of a satellite trail appearing in an image rose by 59% and 71%, respectively.

As it stands now, the risk of satellite streaks is low. But it won't stay low. More satellites are launched every year, and with companies like Starlink and OneWeb poised to launch even more, the problem will quickly become more acute.

"The fraction of HST images crossed by satellites is currently small with a negligible impact on science," the researchers write. "However, the number of satellites and space debris will only increase in the future."

There's been a pronounced increase in satellites since 2009, and that trend will continue. "There has been a 40% increase in the number of artificial satellites in the period 2005–2021, matching the observed increase in the fraction of satellites in HST images (roughly 50% increase,)" the authors say.

Starlink attracts most of the attention in this issue because Musk attracts so much media attention. But the problem is much larger than Starlink. Other companies like the British satellite provider OneWeb and the Chinese company Galaxy Space are part of it. These companies tout the benefits of their satellites, and they have their supporters.

Marian Selorm Sapah is a Lecturer and Research Scientist at the University of Ghana. In a March 2023 piece in The Conversation, Sapah pointed out how uneven internet access is around the world. In Central Africa, only 24% of people have internet access, and that access is heavily favoured toward urban areas. Starlink and others can help alleviate this global inequality, according to Sapah. "Services like Starlink could fuel even greater growth in several areas," Sapah writes. "These include education, participation in democracy and governance, disaster risk reduction and mitigation, health, and agriculture."

Those benefits are hard to deny, and there've been efforts to mitigate the effect that Starlink has on astronomy. The DarkSat is Starlink's attempt to make their satellites less obtrusive by painting them black. While reports say that DarkSat is less bright, the solar panels can't be painted, which puts a strict limitation on dimming efforts. The dark paint caused the satellites to heat up, so it was abandoned. Another method being tried is the so-called VisorSat. It's a sunshade-like device that lowers the satellite's brightness and has been somewhat effective.

Image correction software can help mitigate the problem. The software can mask the streaks and trails, but streaks that are more than a few pixels wide may always be a problem. You can only mask so much of an image before it loses its scientific value. Observing time on the Hubble is in high demand, and that's another dimension of the problem. "Taking shorter exposures can alleviate some of the problems, but one will have to account for the telescope time lost with unusable images," the authors explain.

The other problem is not seen in visible light but in radio brightness. All of these satellites produce a growing background noise in radio astronomy. Black paint and visors won't help.

This issue won't go away. And the astronomy community is raising the alarm.

In a November 2022 article in Scientific American, journalist Rebecca Boyle talked to astronomers who are very concerned with satellite constellations and their effect on astronomy. "The more meetings I attend about this, where we explain the impact it is going to have, the more I get frightened about how astronomy is going to go forward," said Rachel Street, an astronomer at Las Cumbres Observatory in California.

In The Conversation, Astronomer Samantha Lawler of the University of Regina has written extensively about the problem. Starlink makes up almost half of the approximately 4,000 operational satellites, according to Lawler. In one article, Lawler points out that soon, 1 in 15 points of light in the night sky will be a satellite. "This will be devastating to research astronomy and will completely change the night sky worldwide," she wrote.

Lawler and her colleagues created a visualization of the night sky, including the orbits of 65,000 proposed satellites from Starlink, OneWeb, Kuiper, and Starnet/GW.

Simulation of an all-sky view of future planned mega-constellations of satellites, which includes 65,000 satellites on their planned orbits, as seen from latitude 50 degrees north (southern Canada, mid-Europe) on the summer solstice. There are hundreds of satellites that are bright enough to be seen by the naked eye that are visible all night long, and thousands of sunlit satellites all night that could significantly affect astronomy research. The night sky would look very different than it does now from a dark location.That visualization shows 65,000 satellites, but there could soon be far more than that. Proposals from various satellite companies show that by the 2030s, there could be 100,000 satellites in LEO. The research article contains a detailed table of the numbers while cautioning that "These numbers are highly uncertain, as each project is reviewed periodically by the different government agencies, and based on private company operations which are subject to change."

It's not just research astronomers that will pay the price. The rest of us will see it, too. In another article, Lawler writes: "No longer will you escape your city for a camping trip and see the stars unobstructed: you will have to look through a grid of crawling, bright satellites no matter how remote your location."

While the authors of this new research letter focus on the Hubble, it won't be the only one affected. Anything with a wide field of view will pay the price for increased global internet access as corporations battle with each other for a position in this growing, lucrative field. The soon-to-be-operational Vera Rubin Observatory (VRO) may suffer the most.

The VRO will see its first light in 2024. By then, there'll be tens of thousands of satellites, including Starlink and others, in the sky. That's a problem for the VRO, which will conduct an extraordinarily wide-field survey of the night sky called the Legacy Survey of Space and Time. It'll image the entire available night sky every few nights with its 8.4-meter primary mirror. One of its jobs is to spot transients like asteroids. It's uncertain what effect the rapidly growing number of satellites will have on its operation.

Though highly unlikely, the worst-case scenario is that satellites blind us to the approach of a dangerous asteroid. Worst-case scenario aside, the satellite population will extract a toll from the VRO. In 2022, the VRO released a statement titled " Vera C. Rubin Observatory – Impact of Satellite Constellations." The statement said, in part, "The estimated 400,000 recent and planned Low Earth Orbit satellites (LEOsats) threaten the discovery potential of the Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST)."

The night sky is part of humanity's inheritance, but there's a lawlessness to Low Earth Orbit, and companies are rushing in before governments or regulatory agencies exert stricter control. If we degrade our night sky just for wider internet availability, we may never get it back. And while satellite internet is filling a void, it's not the only way to fill it. Earthbound infrastructure could fill the void, just not as easily or cheaply.

There's an equation at the center of this issue. On one side is greater internet access, and on the other is the natural night sky. But can any of us honestly say that the bulk of internet traffic is so important that astronomy, science, and human wonder should take a backseat? The more we drown out nature, the worse off we'll be. And among all the useful things that happen on the internet, there's also a wasteland of memes, pornography, Karen Tik-Toks, gambling, victimization, and endless scams.

That stuff is part of any real conversation about satellite constellations and their effect on the sky.

"On your next clear night, go outside and look up," Lawler writes in The Conversation. "Enjoy the stars that you can see now because, without big changes in the plans of corporations that want to launch mega-constellations, your view of the stars is about to change dramatically."

That statement might be a bit hyperbolic but certainly speaks to the tangible fear in the astronomy community. Hopefully, satellite operators will continue to work on their designs, astronomers can figure out how to work around them, and satellites and telescopes can learn to get along.

More:

- Research Letter: The impact of satellite trails on Hubble Space Telescope observations

- Research Paper: Concerns about ground-based astronomical observations: A step to Safeguard the Astronomical Sky

- Universe Today: With Better Communication, Astronomers and Satellites can co-Exist

- Universe Today: Astronomers Have Some Serious Concerns About Starlink and Other Satellite Constellations

Universe Today

Universe Today