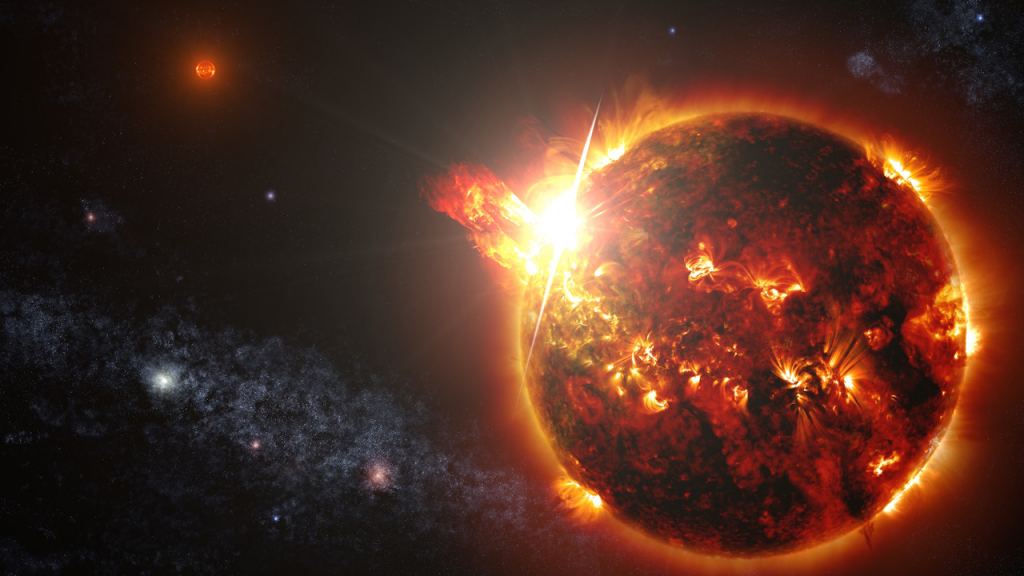

There's something menacing about red dwarfs. Human eyes are accustomed to our benevolent yellow Sun and the warm light it shines on our glorious, life-covered planet. But red dwarfs can seem moody, ill-tempered, and even foreboding.

For long periods of time, they can be calm, but then they can flare violently, flashing a warning to any life that might be gaining a foothold on a nearby planet.

Red dwarfs (M dwarfs) are the most common type of star in the Milky Way. This means that most exoplanets orbit red dwarfs, not nice, well-behaved G-type stars like our Sun. As astronomers study red dwarfs in greater detail, they've found that red dwarfs might not be the best stellar hosts when it comes to exoplanet habitability. Multiple studies have shown that red dwarfs can flare violently, emitting enough powerful radiation to render nearby planets uninhabitable, even when they're firmly in the potentially habitable zone.

But there's still a lot astronomers don't know about red dwarfs and their wild nature. A new study examined 177 M-dwarfs to better understand their long-term variability. The researchers found that red dwarf behaviour is more complex than thought, and even the calmest red dwarfs are wilder than the Sun.

The study is titled " Characterisation of stellar activity of M dwarfs. I. Long-timescale variability in a large sample and detection of new cycles. " The paper will be published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. The lead author is Lucile Mignon, a post-doctoral researcher from the University Grenoble Alpes and the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS.)

All stars are variable to one degree or another. The Sun follows an 11-year cycle during which the number of sunspots on our star's surface waxes and wanes. It's all related to magnetic activity. But habitability hinges on longer-term cycles. Life advances in much longer timeframes than a few years. It took life on Earth billions of years to really get going.

That's one of the reasons astrophysicists are interested in red dwarfs and their long-term variability. Life appeared on Earth about 3.5 billion years ago, but complex life only really emerged about 540 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion. If life follows a similar time frame in general, could red dwarf variability prevent life from enduring?

Observing red dwarfs and reaching any conclusions is a difficult challenge. We can watch our Sun in great detail, especially in recent years. A fleet of spacecraft—including the Parker Solar Probe, the Solar Orbiter, the Solar and Heliospheric Orbiter, and others—are dedicated to monitoring it in detail. We've also observed the Sun and its activity over a long time period.

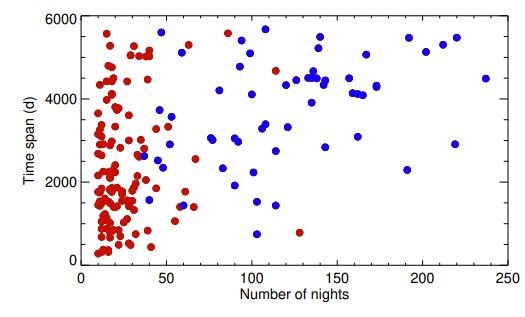

Unfortunately, we haven't been able to monitor individual red dwarfs for extremely long time periods. Instead, researchers have to make do with data sets that span a couple of decades or so. In this new research, Mignon and her co-authors examined 177 M dwarfs observed by HARPS (High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) from 2003 to 2020. Activity in this time scale contains clues to how these stars behave over longer periods.

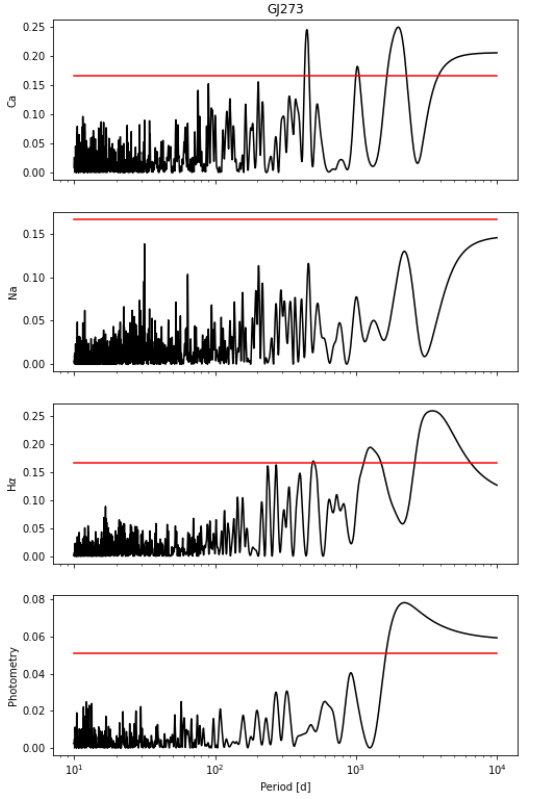

HARPS is essentially a spectrograph, and from it, the authors of this study garnered chromospheric emissions for the red dwarfs. Chromospheric emissions stem from a star's magnetic field activity rather than its fusion. Flaring is an artifact of magnetic activity, so studying flaring means studying a star's chromosphere. The team also analyzed the red dwarfs' photometric characteristics alongside the chromospheric emissions.

The difficulty in studying red dwarf variability stems from our limited long-term data. "The unambiguous identification of a cycle requires measurements showing its repetition over several periods. This requires data taken over a long period of time," they explain.

Lacking that, the researchers worked with the idea of what they call 'seasons.' By identifying seasons for individual stars, they could analyze the data better. "We defined these seasons as bins of 150 days (to average the rotational modulation as best possible) with at least five observations (150 days is the typical maximum limit for the rotation period of M dwarfs), and gaps between observations shorter than 40 days inside a 150-day bin," they explain.

That identified a sub-sample of 57 stars.

The results show that variability is a defining feature among M dwarfs. "We find that most stars are significantly variable, even the quietest stars," the researchers wrote. "Most stars in our sample (75%) exhibit a long-term variability, which manifests itself mostly through linear or quadratic variability, although the true behaviour may be more complex." (Linear variability is more simple, while quadratic variability suggests a cycle.)

The researchers found cycles in their sample ranging from several years to more than 20 years. But they're quick to point out that their findings have limitations and that their study is just an initial step towards a better understanding of red dwarfs. For many of the stars, there's a strong indication that long-term variability exists. "... better-sampled stars might exhibit a more complex behaviour if they had been better sampled," they write. But still, their results are "... indicative of the strong presence of long-term variability, however, and indicates that these stars have a strong long-term variability, which is important when searching for exoplanets."

There could be multiple layers of cycles and variability that affect one another, making the stars' behaviour very difficult to decipher. Their puzzling behaviour "... may be due to a complex underlying variability at different timescales simultaneously," the authors write.

The researchers say that even with their limited data, they've made progress. "Even if the time coverage is not sufficient for some stars, however, our data can be used to estimate a minimum cycle period if present." But some conclusions are beyond reach for now. Their analysis "... is not sufficient to guarantee that the signal is periodic or even quasi-periodic."

A slam-dunk answer for red dwarf habitability is out of reach for now. It may be that, as this study hints, there's so much variability between red dwarfs that they're forever unpredictable. But don't bet against science uncovering more detail.

Red dwarf flaring is well-documented. The most powerful stellar flare ever detected came from a red dwarf. In 2019, Proxima Centauri, a red dwarf and our nearest stellar neighbour emitted a flare 14,000 times brighter than its pre-flare luminosity, and it only took a few seconds to flare that brightly. The exoplanet Proxima Centauri b sits in the star's potentially habitable zone, and a flare that bright could eliminate the possibility of life or even liquid water on the planet. Even if Proxima Centauri flared that brightly once every one million years, or even longer, that could eliminate the possibility of life.

The search for life or habitability on other worlds inevitably includes a focus on red dwarfs. Their plentifulness means they have to be studied in more depth. It could end up that many of the planets we think could be habitable, like the well-known TRAPPIST-1 planets, are simply subjected to too much radiation from their red dwarf hosts. The more variable they are, the less likely life is to persist and even flourish on exoplanets around red dwarfs.

More:

- Published Research: Characterisation of stellar activity of M dwarfs. I. Long-timescale variability in a large sample and detection of new cycles

- Universe Today: Are Planets Tidally Locked to Red Dwarfs Habitable? It’s Complicated

- Universe Today: Another Reason Red Dwarfs Might Be Bad for Life: No Asteroid Belts

Universe Today

Universe Today