Alpha Centauri is our closest stellar neighbor, a binary star system located just 4.376 light-years away. Despite its proximity, repeated astronomical surveys have failed to find hard evidence of extrasolar planets in this system. Part of the problem is that the system consists of two stars orbiting each other, which makes detecting exoplanets through the two most popular methods very challenging. In 2019, Breakthrough Initiatives announced they were backing a new project to find exoplanets next door - the Telescope for Orbit Locus Interferometric Monitoring of our Astronomical Neighbourhood (TOLIMAN, after the star's ancient name in Arabic).

This low-cost mission concept was designed by a team from the University of Sydney, Australia, and aims to look for potentially-habitable exoplanets in the Alpha Centauri system using the Astrometry Method. This consists of monitoring a star's apparent position in the sky for signs of wobble, indicating that gravitational forces (like planets) are acting on it. Recently, the University of Sydney signed a contract with EnduroSat, a leading microsatellites and space services provider, to provide the delivery system and custom-built minisatellite that will support the mission when it launches.

Alpha Centauri consists of a G-type primary star (similar to our Sun) and a K-type (orange dwarf) secondary. Because of its binary nature, it has been very difficult to discern possible signals from this system that could be the result of exoplanets. This includes the Transit Method, where astronomers monitor stars for periodic dips in luminosity that may indicate planets passing in front of the star (transiting) relative to the observer. But since the stars also make transits, dips in luminosity are very common.

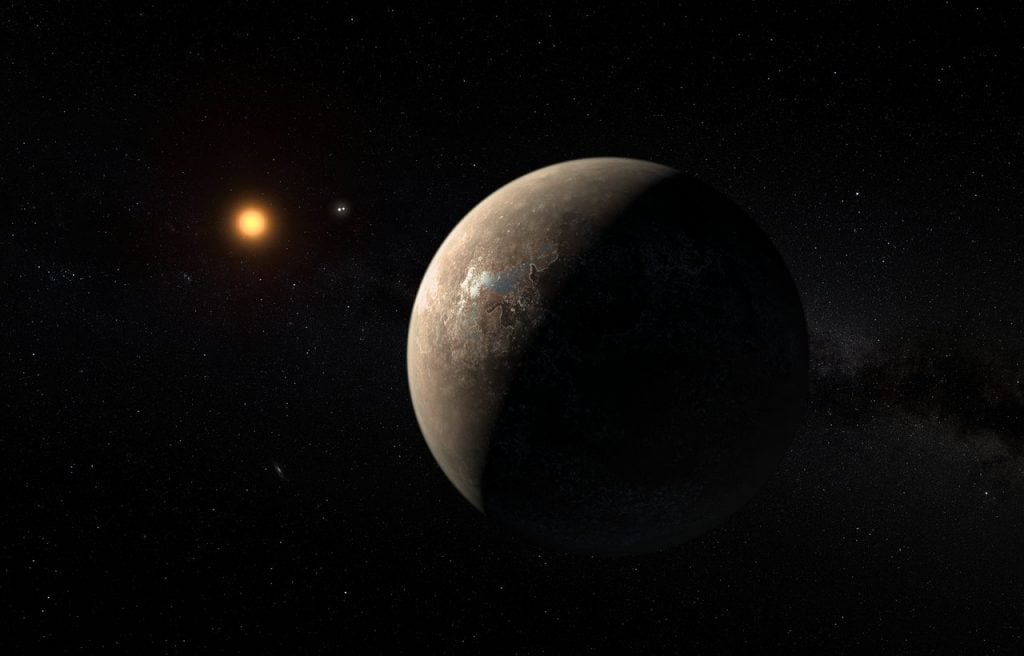

Similarly, the way the stars co-orbit each other significantly affects their movement back and forth (aka. radial velocity). This makes it very difficult to detect planets that could be orbiting them, as indicated by how their gravitational influence affects the star's movement (the Radial Velocity Method). However, this same method confirmed the existence of a rocky planet (Proxima b) orbiting within Proxima Centauri's habitable zone in 2016. Two more have been found since, including an innermost Mars-sized rocky planet and an outermost gas giant (possibly with rings!)

So far, astronomers have reported numerous possible signals from Alpha Centauri. The first occurred in 2012 when astronomers reported an RV signal from Alpha Centauri B that was attributed to a planet (Alpha Centauri Bb) but which was revealed to be a false positive in 2015. A possible planetary transit was announced in 2013, but it was reportedly too close to its primary to support life. In 2021, a candidate planet named Candidate 1 (C1) was detected around Alpha Centauri A using direct thermal imaging, but this remains unconfirmed.

To Peter Tuthill, a professor of physics with the Sydney Institute for Astronomy (SIfA) and the lead scientist on the TOLIMAN mission, the difficult task of confirming planets around Alpha Centauri A and B is too tempting to pass up. As he said in a recent University of Sidney press release:

"That's tantalizingly close to home. Astronomers have discovered thousands of exoplanets outside our own Solar System, but most are thousands of light years away and beyond our reach. Modern satellite technology will allow us to explore our celestial backyard and perhaps lay the groundwork for visionary future missions spanning the interstellar voids to the Centauri system."

As we explored in a previous article, the TOLIMAN concept was first proposed by Tuthill and his SIfA colleagues during the 2018 SPIE Astronomical Telescopes+Instrumentation Conference in Austin, Texas. Rather than concentrating light into a focused beam like conventional telescopes, the TOLIMAN relies on a diffractive pupil mirror pattern that spreads starlight into a complex flower pattern, allowing for extremely fine measurements of a star's motion. Any indications of exoplanets can then be followed by more powerful instruments not dedicated exclusively to monitoring Alpha Centauri.

"Any exoplanets we find that close to Earth can be followed up with other instruments, giving excellent prospects for discovering and analyzing atmospheres, surface chemistry, or even fingerprints of a biosphere – the tentative signs of life," said Tuthill. These follow-up studies are something telescopes like the James Webb* and the next-generation instruments like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope* (RST), scheduled to launch in 2027. Alpha Centauri is also likely to be a popular target for the many 30-meter ground-based telescopes that will become operational in this decade.

Launching this telescope will be a tall order, requiring a limited volume (12 liters) that can maintain thermal and mechanical stability. To this end, the Universtiy of Sydney has contracted with EnduroSat to provide a custom-built mini satellite as the delivery system. Their MicroSat design can downlink payload data at a speed of more than 125 megabits per second (Mbps), which is crucial for an ongoing observation mission where lots of data downloads will come into play. As Raycho Raychev, the Founder and CEO of EnduroSat, remarked:

"We are exceptionally proud to partner in this mission. The challenges are enormous, and it will drive our engineering efforts to the extreme. The mission is a first-of-its-kind exploration science effort and will help open the doors for low-cost astronomy missions."

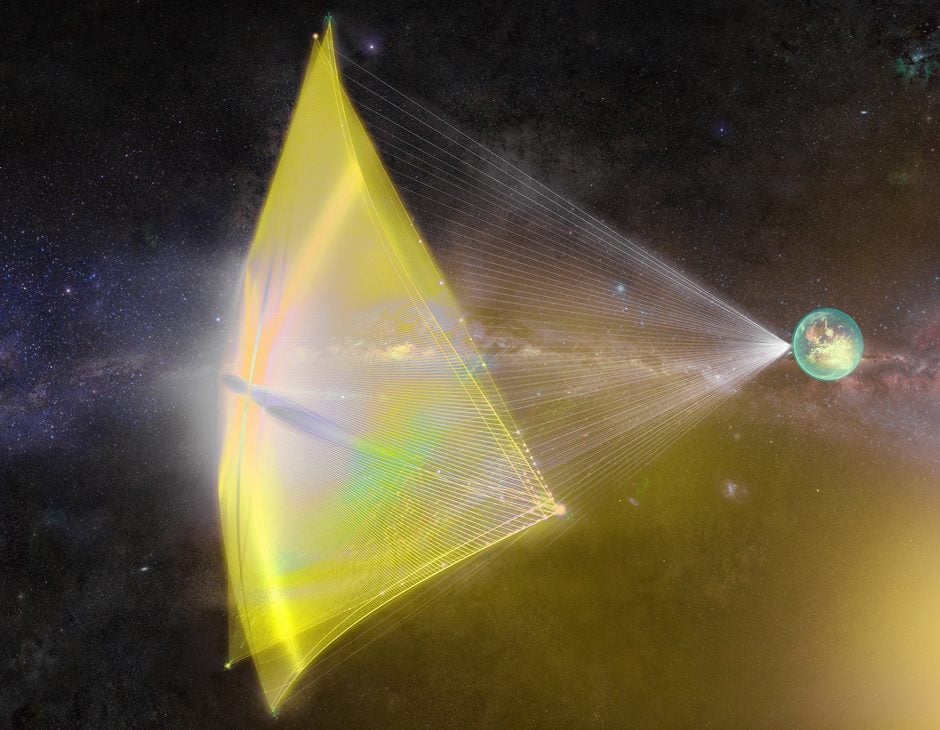

This latest project is one of several backed by Breakthrough Initiatives, which is already having an impact with its advanced project Breakthrough Listen - the largest program ever mounted dedicated to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI). The TOLIMAN project also fits nicely with Breakthrough Starshot, a proposed interstellar mission that will leverage advances in miniaturization, advanced materials, and directed-energy propulsion to send a nanocraft to Alpha Centauri within a single lifetime (20 years).

Detecting planets next door will likely go a long way toward inspiring interstellar missions to explore the system up close. Said Dr. S. Pete Worden, the former director of NASA's Ames Research Center (2006 to 2015) and the Executive Director of Breakthrough Initiatives: "It's very exciting to see this program come to life. With these partnerships, we can create a new kind of astronomical mission and make real progress on understanding the planetary systems right next door."

*Further Reading: University of Sydney*

Universe Today

Universe Today