The surface of Mars is a pretty desolate place at first glance. The soil is many times as dry as the driest desert on planet Earth, the temperatures swing from one extreme to the other, and the air is incredibly thin and toxic. And yet, there’s ample evidence that the planet was once much warmer and wetter, with lots of flowing and standing water on its surface. Over time, as Mars’ atmosphere was slowly stripped away, much of this water was lost to space, and what remains is largely concentrated around the poles as glacial ice and permafrost.

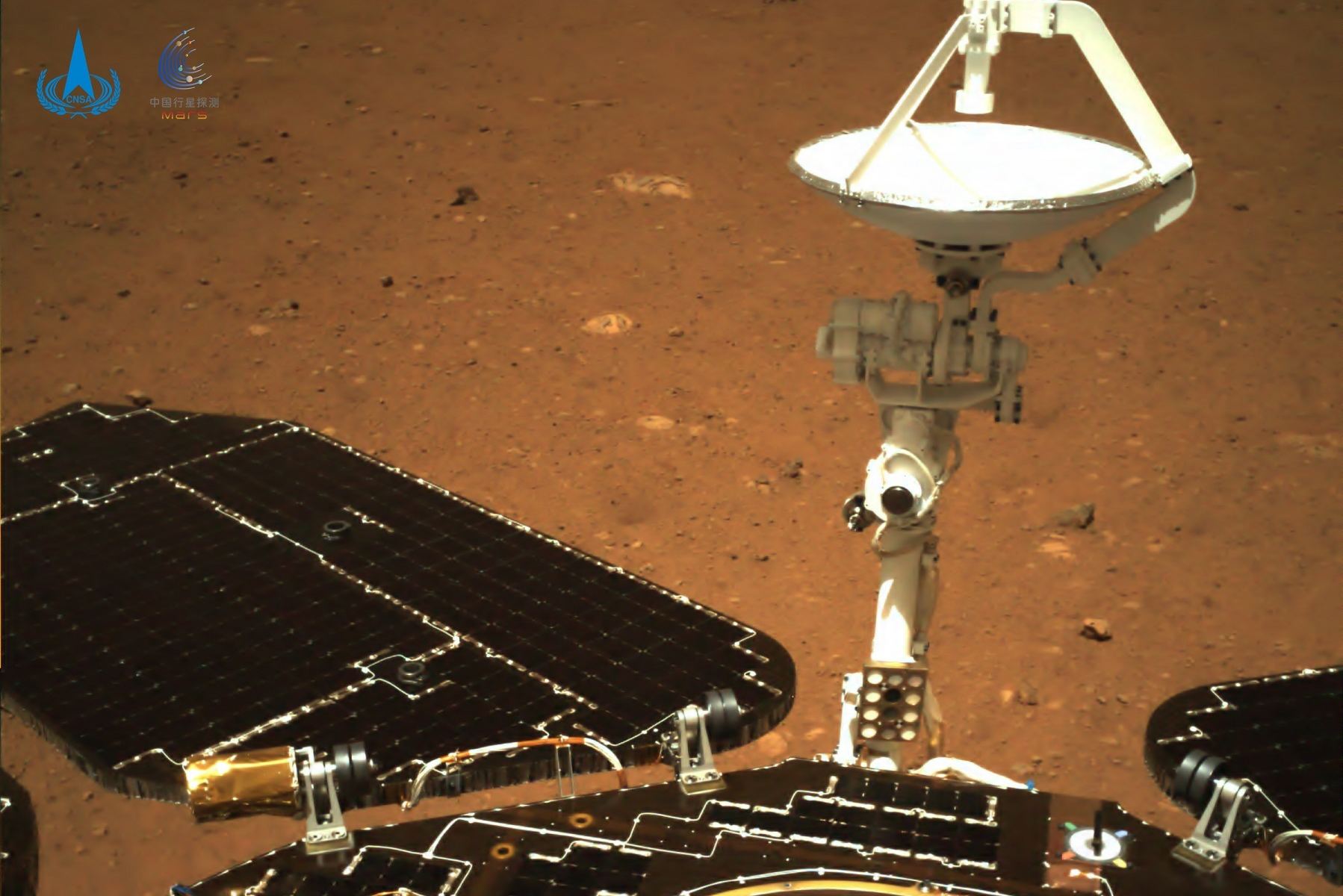

For years, space agencies have been sending robotic landers, rovers, orbiters, and aerial vehicles to Mars to learn more about when this transition took and how long it took. According to China’s Tianwen-1 mission, which includes the Zhurong rover, there may have been liquid water on the Martian surface later than previously thought. According to new research from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), the Zhurong rover observed salt-rich dunes in the Utopia Planitia region that showed cracks and crusts, indicating the possible presence of water as recently as a few hundred thousand years ago.

The research team was co-led by Xiaoguang Qin and Xu Wang of the Key Laboratory of Cenozoic Geology and Environment at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics; and Xin Ren and Jianjun Liu of the Key Laboratory of Lunar and Deep Space Exploration (part of the National Astronomical Observatories). They were joined by many additional researchers from these respective institutions, the College of Earth and Planetary Sciences, and the Institute of Atmospheric Physics. Their findings were described in a paper that appeared in Science Advances on April 28th.

As they describe, the Zhurong rover observed interesting features on the surfaces of Barchan dunes in Utopia Planitia, a massive plain and the largest impact basin in the Solar System. These dunes are a characteristic feature in Mars’ northern hemisphere that are similar to dunes that appear in deserts all across Earth. These result from high winds depositing sand in a crescent shape, with the curved side facing in the direction of the wind. When observing a patch of dunes in the southern part of Utopia Planitia, Zhurong noted crusts, cracks, aggregates, and bright polygonal ridges.

The team concluded that these features were formed from small pockets of water from thawing frost or snow mixed with mineral salts. Once the water sublimated in Mars’ atmosphere, patches of hard crust and loose material were left behind, along with depressions and ridges. Like other features that formed in the presence of water, these were then preserved by Mars’ extremely cold and dry atmosphere. But unlike other features that are hundreds of eons or billions of years old, the team estimates that these features formed between 1.4 million and 400,000 years ago (perhaps even more recently).

As they explain in their paper, the team was able to rule out the possibility that frozen carbon dioxide (“dry ice”) and wind were responsible:

“Instead, involvement of saline water from thawed frost/snow is the most likely cause. This discovery sheds light on more humid conditions of the modern Martian climate and provides critical clues to future exploration missions searching for signs of extant life, particularly at low latitudes with comparatively warmer, more amenable surface temperatures.”

During the period in question, the Martian environment was much as it is today (i.e., extremely cold and dry). Therefore, these findings indicate that a hydrological cycle existed recently on Mars, far more recent than previously thought. The team also ran computer simulations and combined them with observations made by other robotic missions. These indicated that conditions could be suitable in other regions on Mars for frost and ice to form during certain times of the year, leading to similar features elsewhere.

This is consistent with observations made by robotic missions since NASA’s Viking 1 and 2 missions explored Mars in the late 1970s. However, scientists were of the general opinion that morning frost only occurred in certain locations and under highly-constrained conditions. This discovery indicates that there could be periodic patches of liquid water on Mars today in other regions, though the amount would be very small. As the study authors state:

“This discovery sheds light on more humid conditions of the modern Martian climate and provides critical clues to future exploration missions searching for signs of extant life, particularly at low latitudes with comparatively warmer, more amenable surface temperatures.”

This discovery could also point toward the existence of small patches of fertile ground where microbial life could still exist today. Of course, additional studies are needed before any of this can be said with confidence. Those studies may or may have to wait on future missions, as the rover has not yet woken up from hibernation. According to Zhang Rongqiao, chief designer of Tianwen-1, this is likely due to the build-up of dust on the rover’s solar panels. Like NASA’s Insight and Opportunity missions, this could prevent the mission from operating ever again.

Since it rolled off of the Tianwen-1 lander on May 22nd, 2021, the rover spent roughly a year exploring the surface of Mars before it went into hibernation on May 20th, 2022. Since it was designed to operate for just 90 Martian days (sols), or 93 Earth days, the rover has vastly exceeded its intended lifespan. As of May 5th, 2022, Zhurong also managed to travel 1,921 meters (1.194 mi) across the surface. If the China National Space Agency is unable to reactivate the rover before long and decides to conclude the mission, Zhurong could not have picked a more profound discovery to go out on!

Further Reading: Phys.org, Science Advances