Jupiter’s moon Io is the most volcanic world in the Solar System, with over 400 volcanoes. Some of them eject plumes as high as 500 km (300 mi) above the surface. Its surface is almost entirely shaped by all this volcanic activity, with large regions covered by silicates, sulphur, and sulphur dioxide brought up from the moon’s interior. The intense volcanic activity has created over 100 mountains, and some of them are taller than Mt. Everest.

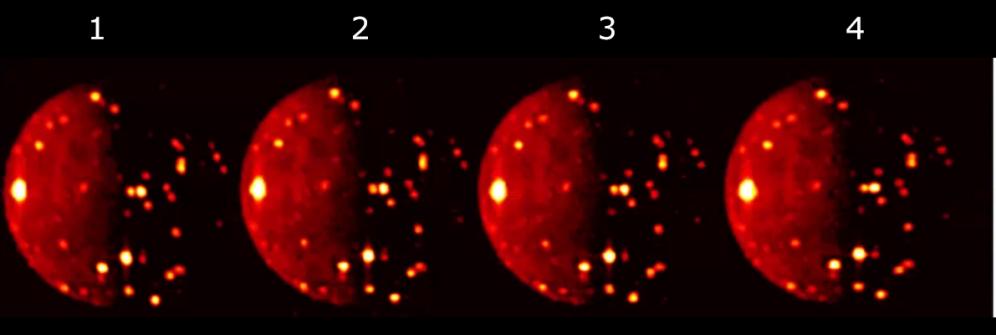

Io is unique in the Solar System, and the Juno orbiter’s JunoCam captured some new images of Io’s abundant volcanic activity.

Io is in a tough position. It’s locked in a kind of gravitational tug-of-war with massive Jupiter and the other Galilean moons, Ganymede, Europe, and Callisto. All that gravitational energy, particularly from Jupiter and Europa, creates friction in the moon’s interior that creates ‘tidal heating.’ That sets it apart from Earth’s volcanism, which is caused largely by the heat from the decay of radioactive isotopes in the mantle, including uranium, potassium, and thorium. In fact, Io produces bout 40% more heat than Earth, an amount that simply cannot be produced by radioactive decay.

While Juno’s images of Io are the newest, they’re not necessarily the best. Voyager 1 and Galileo both got closer to Io than Juno did, and their images of the surface are even more stunning.

But Juno’s much more modern instruments allow it to study Io’s volcanic nature in greater detail. This is important because of some questions scientists would like answers to. Although there’s widespread scientific agreement that tidal heating creates the heat driving all of the moon’s volcanic activity, the heating doesn’t create the volcanoes where we expect them to be, according to our best scientific understanding. One of Juno’s goals is to image the moon’s surface over time to build a more comprehensive picture of the moon’s volcanic activity.

Io has about 115 named mountains, and their average height is about 6,300 m (20,700 ft). Boösaule Montes, at 17,500 metres (57,400 ft) is Io’s tallest moon. Compare that to Mt. Everest’s height of almost 8,850 meters (29,035 ft.) And Io is only 3600 km in diameter, compared to Earth’s 12,700 km diameter. Mountains can be so high on smaller bodies because they have weaker gravity.

Most of what scientists know about Io’s volcanism comes from the Galileo and Cassini missions. And even after decades of research, there are still questions about the moon’s abundant volcanic activity and the conditions in the interior that cause it. Juno is not primarily aimed at studying Io, but we’re about to get our best look at Io so far.

Yesterday, Tuesday, May 16th, the spacecraft came to within 35,500 km of Io’s surface.

“Io is the most volcanic celestial body that we know of in our solar system,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “By observing it over time on multiple passes, we can watch how the volcanoes vary – how often they erupt, how bright and hot they are, whether they are linked to a group or solo, and if the shape of the lava flow changes.”

Future flybys later this year will come even closer, down to only 1500 km. The combined images from all of these flybys will reveal a lot.

“We are entering into another amazing part of Juno’s mission as we get closer and closer to Io with successive orbits. This 51st orbit will provide our closest look yet at this tortured moon,” said Bolton. “Our upcoming flybys in July and October will bring us even closer, leading up to our twin flyby encounters with Io in December of this year and February of next year when we fly within 1,500 kilometres of its surface. All of these flybys are providing spectacular views of the volcanic activity of this amazing moon. The data should be amazing.”

An even greater understanding of Io should come if NASA approves the Io Volcano Observer mission. Its goals are to understand in more detail how the moon is tidally heated, how that heat is transported to the surface, and how Io is evolving.

Io’s heat transport mechanism is much different than Earth’s. Earth transports heat from the interior to the surface through plate tectonics, where large slabs of cold oceanic crust are subducted into the warm mantle. But Io loses heat through what are known as heat pipes, and these heat pipes cover only about 1% of the moon’s surface.

Those results, if the mission is approved, should shed light on Europa’s complex nature. It’ll also shed light on other tidally heated moons like Enceladus and Titan. Scientists are also hopeful that it could tell us something about magma oceans, like those experienced by the early Moon and probably Earth.

Even with Juno’s imaging efforts, and the results from Cassini, Galileo, and the Voyagers, there’s a lot scientists don’t know about Io. Galileo’s detailed study of the Jupiter system provided the most information on this geologically hyperactive world and also led to more questions, such as:

- Is the tidal heating produced in Io’s shallow mantle, or is it widespread?

- Is there a magma ocean in the form of a global layer of melt under Io’s crust?

- Is Io’s magma ocean in any way similar to subsurface oceans on other moons like Europa?

Those answers await the eventual launch of the Io Volcano Voyager, if it’s ever approved, or another similar mission. Until then, Juno is the only spacecraft in the vicinity, and scientists are gleaning what information they can from Juno’s images and data.

More:

- Press Release: NASA’s Juno Mission Getting Closer to Jupiter’s Moon Io

- JPL NASA Photojournal: 4 Looks at Io Volcanoes

- Universe Today: Jupiter’s Moon Io has Dunes. Dunes!?