When astronomers discovered WASP-18b in 2009, they uncovered one of the most unusual planets ever found. It's ten times as massive as Jupiter is, it's tidally locked to its Sun-like star, and it completes an orbit in less than one Earth day, about 23 hours.

Now astronomers have pointed the JWST and its powerful NIRSS instrument at the ultra-Hot Jupiter and mapped its extraordinary atmosphere.

Ever since its discovery, astronomers have been keenly interested in WASP-18b. For one thing, it's massive. At ten times more massive than Jupiter, the planet is nearing brown dwarf territory. It's also extremely hot, with its dayside temperature exceeding 2750 C (4900 F.) Not only that, but it's likely to spiral to its doom and collide with its star sometime in the next one million years.

For these reasons and more, astronomers are practically obsessed with it. They've made extensive efforts to map the exoplanet's atmosphere and uncover its details with the Hubble and the Spitzer. But those space telescopes, as powerful as they are, were unable to collect data detailed enough to reveal the atmosphere's properties conclusively.

Now that the JWST is in full swing, it was inevitable that someone's request to point it at WASP-18b would be granted. Who in the Astronomocracy would say no?

In new research, a team led by a Ph.D. student at the University of Montreal mapped WASP-19b's atmosphere with the JWST. They used the NIRISS instrument, one of Canada's contributions to the JWST. The paper is " A broadband thermal emission spectrum of the ultra-hot Jupiter WASP-18b. " It's published in Nature, and the lead author is Louis-Philippe Coulombe.

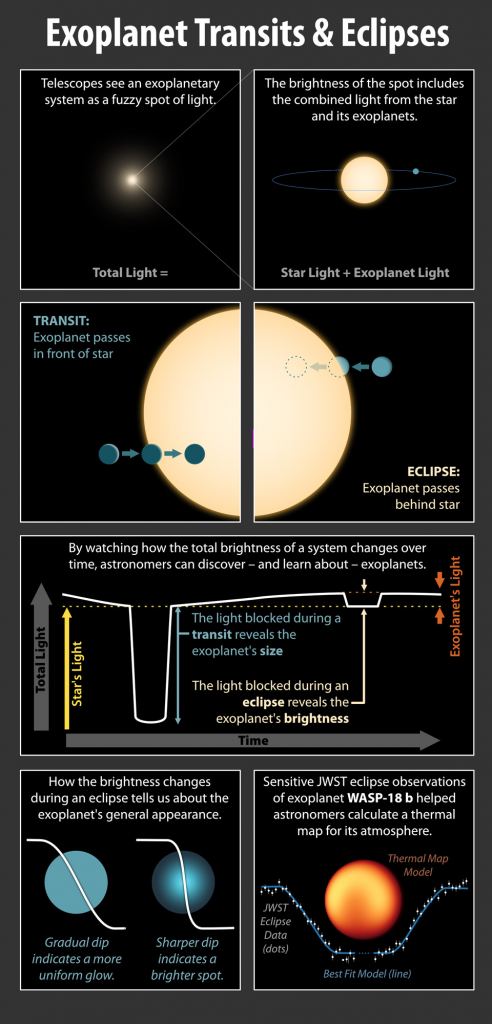

The researchers trained Webb's NIRISS (Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph) on the planet during a secondary eclipse. This is when the planet passes behind its star and emerges on the other side. The instrument measures the light from the star and the planet, then during the eclipse, they deduct the star's light, giving a measurement of the planet's spectrum. The NIRISS' power gave the researchers a detailed map of the planet's atmosphere.

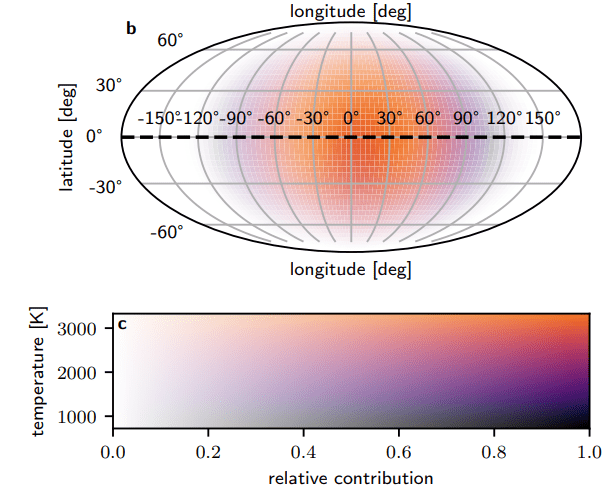

With the help of NIRISS, the researchers mapped the temperature gradients on the planet's dayside. They found that the planet is much cooler near the terminator line: about 1,000 degrees cooler than the hottest point of the planet directly facing the star. That shows that winds are unable to spread heat efficiently to the planet's nightside. What's stopping that from happening?

"JWST is giving us the sensitivity to make much more detailed maps of hot giant planets like WASP-18 b than ever before. This is the first time a planet has been mapped with JWST, and it's really exciting to see that some of what our models predicted, such as a sharp drop in temperature away from the point on the planet directly facing the star, is actually seen in the data!" said paper co-author Megan Mansfield, a Sagan Fellow at the University of Arizona.

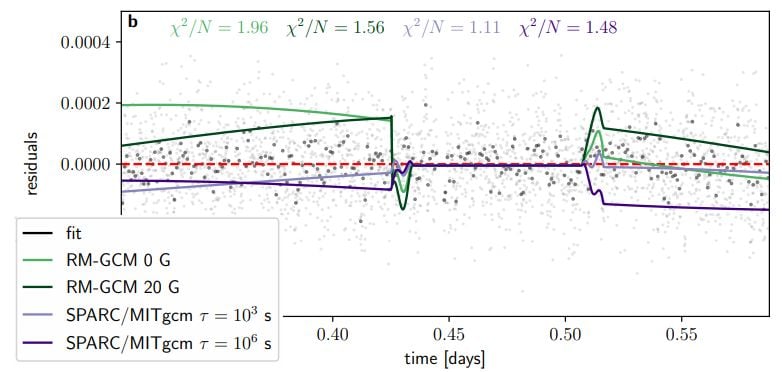

The lack of winds moving the atmosphere around and regulating the temperature is surprising, and atmospheric drag has something to do with it.

"The brightness map of WASP-18 b shows a lack of east-west winds that is best matched by models with atmospheric drag," said co-author Ryan Challener, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Michigan. "One possible explanation is that this planet has a strong magnetic field, which would be an exciting discovery!"

In our Solar System, Jupiter has the strongest magnetic field. Scientists think that swirling conducting materials deep inside the planet, near its bizarre liquid, metallic hydrogen core generates the magnetic fields. The fields are so powerful that they protect the three Galilean moons from the solar wind. They also generate permanent aurorae and create powerful radiation belts around the giant planet.

But WASP-18 b is ten times more massive than Jupiter, and it's reasonable to think its magnetic fields are even more dominant. If the planet's magnetic field is responsible for the lack of east-west winds, it could be forcing the winds to move over the North Pole and down the South Pole.

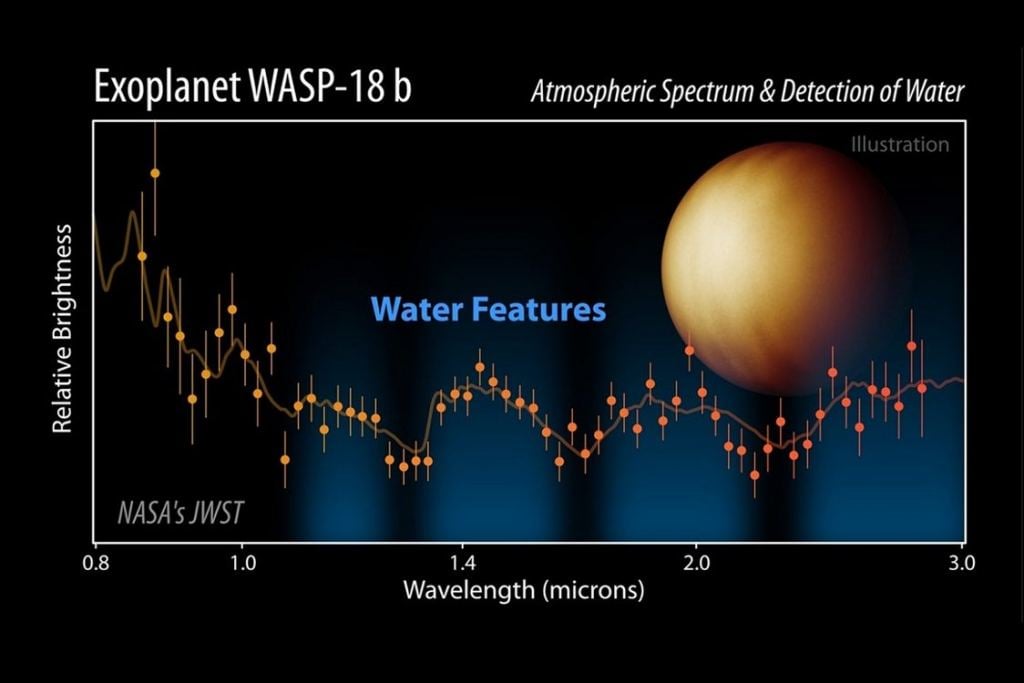

The researchers were also able to measure the atmosphere's temperature at different depths. Temperatures increased with altitude, sometimes by hundreds of degrees. They also found water vapour at different depths.

At 2,700 Celsius, the heat should tear most water molecules apart. The fact that the JWST was able to spot the remaining water speaks to its sensitivity.

"Because the water features in this spectrum are so subtle, they were difficult to identify in previous observations. That made it really exciting to finally see water features with these JWST observations," said Anjali Piette, a postdoctoral fellow at the Carnegie Institution for Science and one of the authors of the new research.

But the JWST was able to reveal more about the star than just its temperature gradients and its water content. The researchers found that the atmosphere contains Vanadium Oxide, Titanium Oxide, and Hydride, a negative ion of hydrogen. Together, those chemicals could combine to give the atmosphere its opacity.

All these findings came from only six hours of observations with NIRISS. Six hours of JWST time is precious to astronomers, and that's all the researchers needed. That's not only because the JWST is so powerful and capable, but also because of WASP-18 b itself.

At only 400 light-years away, it's relatively close in astronomical terms. Its proximity to its star also helped, and the planet is huddled right next to its star. Plus, WASP-18 b is huge. In fact, it's one of the most massive planets accessible to atmospheric investigation.

The planet's atmospheric properties also provide clues to its origins. Comparisons of metallicity and composition between planets and stars can help explain a planet's history. WASP-18 b couldn't have formed in its current location. It must have migrated there somehow. And while this work can't answer that conclusively, it does tell us other things about the giant planet's formation.

"By analyzing WASP-18 b's spectrum, we not only learn about the various molecules that can be found in its atmosphere but also about the way it formed. We find from our observations that WASP-18 b's composition is very similar to that of its star, meaning it most likely formed from the leftover gas that was present just after the star was born," Coulombe said. "Those results are very valuable to get a clear picture of how strange planets like WASP-18 b, which have no counterpart in our Solar System, come to exist."

Universe Today

Universe Today