The Sun dominates the Solar System in almost every way imaginable, yet much of its inner workings have been hidden from humanity. Over the centuries, and especially in the last few decades, technological advancements allowed us to ignore our mothers' exhortations and stare at the Sun for as long as we want. We've learned a lot from all those observations.

A new study shows how the Sun experiences its own 'meteor showers.'

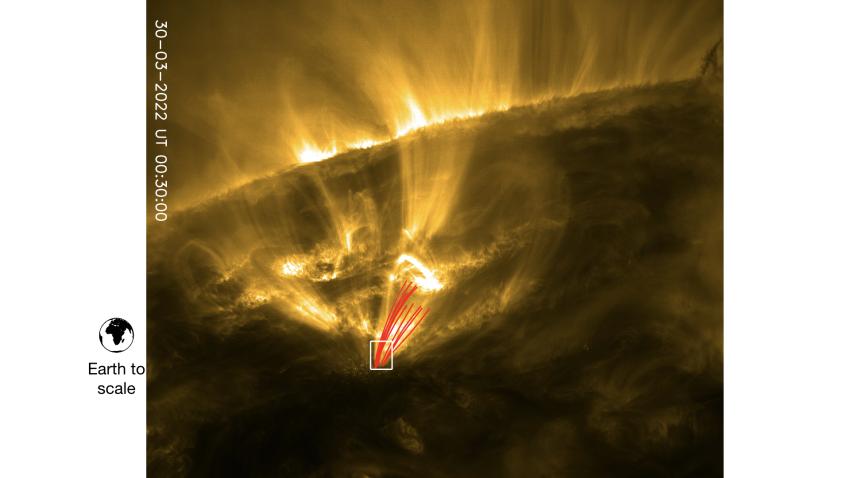

These so-called meteor showers are nothing like the meteor showers we enjoy on a summer's evening. Instead, they're clumps of plasma formed by localized cooling. The European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter captured images of them.

A meteor shower occurs when Earth passes through a cloud of dust particles, usually from a passing comet. As these tiny particles strike Earth's atmosphere, the friction heats them up, and they burn. Some meteor showers produce more than 1000 meteors per hour.

There are no meteor showers on the Sun. Its powerful solar wind prevents dust from encroaching into its space. But new research from European scientists shows that there's something strange going on in the Sun. Meteor-like fireballs of plasma can fall onto its surface.

A team of researchers headed by Patrick Antolin, Assistant Professor at Northumbria University, presented their results at the National Astronomy Meeting at Cardiff University. They'll also be published in a forthcoming paper in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics titled " Extreme-ultraviolet fine structure and variability associated with coronal rain revealed by Solar Orbiter/EUI HRIEUV and SPICE. "

Astrophysicists call this unusual phenomenon 'coronal rain.' The corona is the Sun's outer layer. It reaches millions of kilometres into space, and it's extremely hot. The extreme heat means the corona is made of plasma. But it's also subject to temperature fluctuations.

"Just detecting coronal rain is a huge step forward for solar physics because it gives us important clues about the major solar mysteries, such as how it is heated to millions of degrees."Patrick Antolin, Northumbria University

When the local temperature drops, the plasma can condense into huge, super-dense clumps. These clumps have nowhere to go but down, back to the Sun. The clumps are enormous, up to 250km wide, according to the new observations. And they don't fall gently. The Sun's powerful gravity drags them down at over 100 km per second.

To capture these images, the Solar Orbiter came within 49 million kilometres of the Sun. This close approach allowed the highest-resolution images ever taken of the Sun's corona. The orbiter also observed the heating and compression of gas immediately below the clumps of solar rain. The temperature and pressure rise dramatically in the clumps, and the temperature gradually falls again as the clumps fall back to the Sun.

When they fall back to the Sun, these clumps don't burn up like Earthly meteor showers. Instead, they're partially ionized and follow the Sun's powerful magnetic field lines as they fall to the surface. The clumps can produce a brief yet strong brightening when they reach the surface. The impacts also produce upward surges of material as well as shock waves, which can heat the material again.

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/F7DuegDqfmE

"The inner solar corona is so hot we may never be able to probe it in situ with a spacecraft," said lead author Patrick Antolin. "However, SolO orbits close enough to the Sun that it can detect small-scale phenomena occurring within the corona, such as the effect of the rain on the corona, allowing us a precious indirect probe of the coronal environment that is crucial to understanding its composition and thermodynamics. Just detecting coronal rain is a huge step forward for solar physics because it gives us important clues about the major solar mysteries, such as how it is heated to millions of degrees."

Purely as a thought experiment, it's fun to think about what would happen if Earth was subjected to these blobs of plasma. A 250 km blob of super-heated plasma would be unimaginably destructive if it struck Earth. Of course, that can't happen; it's purely speculative. But it is another reminder of how puny and helpless humanity is in the face of nature's lethality.

"If humans were alien beings capable of living on the Sun's surface, we would constantly be rewarded with amazing views of shooting stars," joked Antolin, "but we would need to watch out for our heads!"

Universe Today

Universe Today