A collaboration of engineers from NASA and academia recently tested hybrid printed electronic circuits near the edge of space, also known as the Kármán line. The space-readiness test was demonstrated on the Suborbital Technology Experiment Carrier-9, or (SubTEC-9), sounding rocket mission, which was launched from NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility on April 25 and reached an altitude of approximately 174 kilometers (108 miles), which lasted only a few minutes before the rocket descended to the ground via parachute.

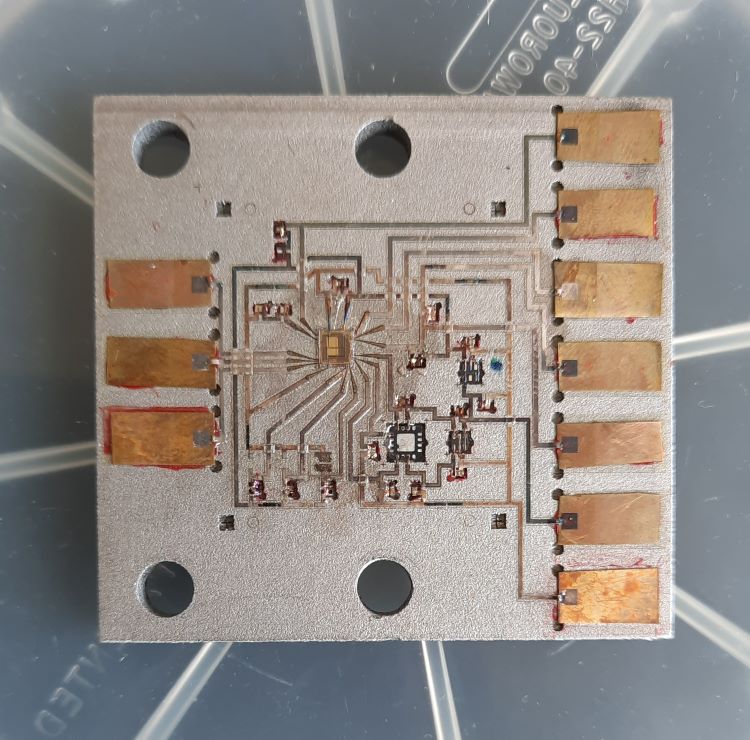

The test consisted of humidity and electronic sensors that were printed on two attached panels along with the payload door, all of which transmitted data to the ground during the brief flight. The mission was deemed a success and holds the potential to help scientists and engineers improve design efficiency for smaller spacecraft.

"The uniqueness of this technology is being able to print a sensor actually where you need it," said Dr. Margaret Samuels, who is an electronics engineer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and co-led the experiment with Goddard aerospace engineer, Beth Paquette. "The big benefit is that it's a space saver. We can print on 3-dimensional surfaces with traces of about 30 microns – half the width of a human hair – or smaller between components. It could provide other benefits for antennas and radio frequency applications."

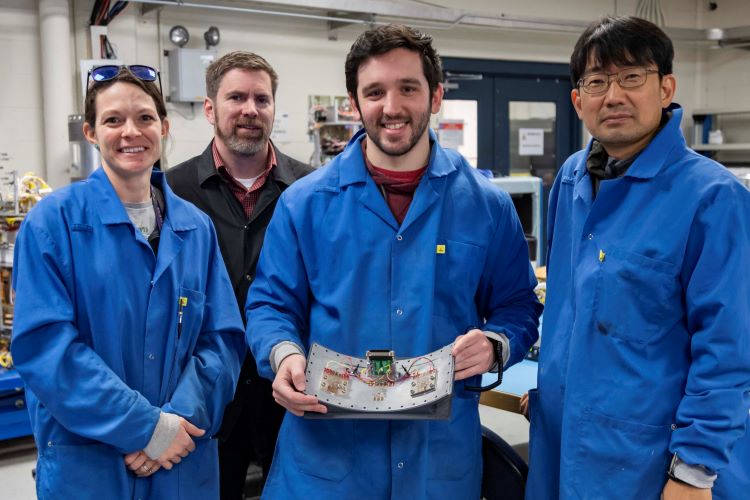

The humidity-sensing printing ink was produced at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center while the circuits were created at the University of Maryland’s Laboratory for Physical Sciences (LPS), who each coordinated their efforts with Dr. Samuels and Paquette, demonstrating the collaborative effort undertaken for the project.

Brian Banks, who is an electronics engineer at Wallops, noted the printed circuits provide a new framework for designing smaller spacecraft, for both near-Earth and deep space mission.

"The hybrid technology allows for circuits to be fabricated in locations that would typically not be available for conventional electronics modules," said Banks. "Printing on curved surfaces could also be helpful for small, deployable sub-payloads where space is very limited."

The circuits were both designed and printed by LPS engineer, Jason Fleischer, who said the SubTEC-9 mission establishes a "turning point" for the evolution and validation of printed-circuit technology at LPS.

According to Paquette, temperature sensors could be printed all over the vehicle's surface interiors on future missions. For example, that type of mission could analyze the heating and cooling of a spacecraft as it travels close to the Sun.

Along with testing the 3D-printed electronic circuits, the SubTEC-9 mission tested a total of 14 different types of technologies. These include a faster telemetry link, a new antenna, a low-cost gyro, a new high-density battery, and a new smaller star tracker, which, as its name implies, is a sensor built to align an object of importance in space, like a star, and is built for altitude control systems.

The SubTEC missions are only a small piece of NASA's Sounding Rockets Program (NSRP), which started in 1959 with the goal of providing research activities for space and earth sciences. During its tenure, NSRP has launched approximately 3,000 missions to suborbital space, achieving a greater than 90 percent mission success rate over the last two decades along with a launch success rate of 97 percent.

The SubTEC-9 sounding rocket mission is the most recent of NASA's SubTEC program, whose first launch was in 2005 with recent flights including SubTEC-7, which occurred on May 16, 2017, and SubTEC-8, which occurred on October 24, 2019.

What new discoveries will scientists and engineers make about 3D-printed electronic circuits in the coming years and decades? Only time will tell, and this is why we science!

As always, keep doing science & keep looking up!

Universe Today

Universe Today