It's every space mission's nightmare: losing contact with the spacecraft. In the best case, you recover it right away. Worst case, you never hear from your hardware again. On July 21, controllers lost contact with Voyager 2, out in the depths of space. Now they're waiting for a reset to catch Voyager 2's next message when it "phones home". (Update: on August 2, NASA announced via its Twitter account that it has received a "heartbeat" carrier signal from the spacecraft.)

So, what happened? The spacecraft, which is nearly 20 billion kilometers away, seems to be doing fine. It's probably sending all kinds of communications back to Earth. But, the stream of data is bounding off into space instead of linking up with the Deep Space network. That's because a series of planned commands to Voyager 2 inadvertently caused the spacecraft to point its antenna 2 degrees away from Earth. Essentially, Voyager 2 and Earth are not in communication. They're "talking past" each other.

Regaining Contact with Voyager 2

All is not lost. Yet. That's because the spacecraft is programmed to reset its orientation several times a year to keep the antenna pointed toward Earth. The next reset isn't for several months—on October 15th. Until then, Voyager 2 is speeding along on its planned trajectory. If all goes well, the control team should hear from the spacecraft again on October 15th. At this point, they're characterizing this loss of signal as a temporary communications pause. There's nothing to indicate any other problems with Voyager 2, beyond the mistaken commands.

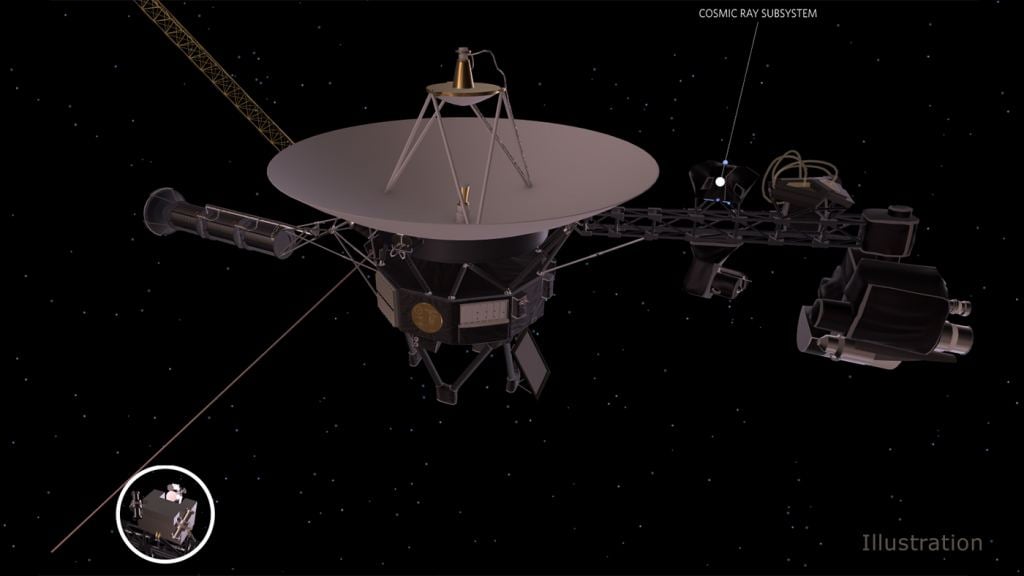

The spacecraft is equipped with a high-gain antenna measuring 3.7 meters across. It communicates with the Deep Space Network via the S band (13 cm wavelength) channel as well as in the X band (3.6 cm wavelength). At its current distance, the spacecraft's signals take about 17.5 hours to get back to Earth. That time increases as the spacecraft gets farther away.

A Glorious History

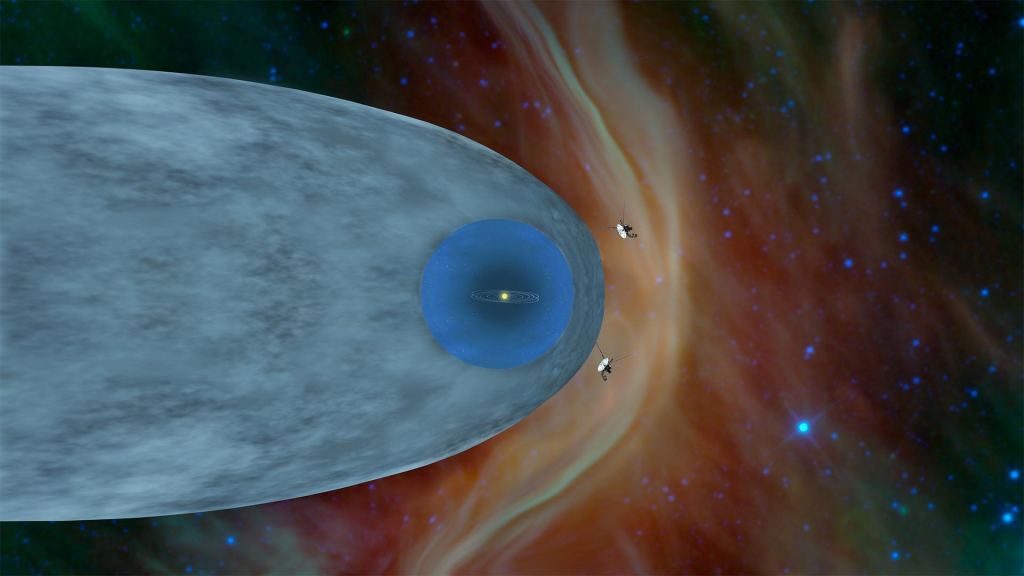

Currently, Voyager 2 and its twin Voyager 1 are exploring space beyond the solar system. They launched in 1977 and for the past decades, they've made huge discovieres at planets and the outermost bounds of the heliosphere. Their images and data opened up a whole new way of looking at the outer solar system.

Now, they're in the Voyager Interstellar Mission phase, where their data helps characterize the "limits" of the solar system lie and where deep space begins. Voyager 2 probably entered interstellar space a few years ago, although it still reports on conditions at the "edge" of the solar system. Interestingly, while Voyager 2 is out of communications with Earth, Voyager 1 is still talking with the Deep Space Network. It's about 24 billion kilometers from Earth.

Ultimately, they're headed out on two very different trajectories through the stars. They have enough power to operate for a few more years (2025 or thereabouts) to send back information to Earth about their environments. Engineers on the project have figured out a way to extend spacecraft power for perhaps a couple more years by tapping some specific onboard reserves. Eventually, however, the spacecraft will fall silent as their power supplies run out. This current outage on Voyager 2 is giving mission engineers an early taste of what that experience will be like, after "talking" with these distant spacecraft for nearly five decades.

For More Information

Mission Update: Voyager 2 Communications Pause

Voyagers Mission Status

Universe Today

Universe Today