For astronomers, the only thing better than new data is more new data. And we seem to be in a golden age of data gathering. We’ve gushed over the latest images from the James Webb Space Telescope and Hubble continues to make observations, but several new space telescopes are lesser known, such as Gaia, TESS, and Swift. And now a new space telescope enters the game, known as Euclid. Euclid is an infrared telescope launched last month by the European Space Agency (ESA). It took 11 years to design and build the telescope, and it has just taken test images with its two primary detectors.

Euclid is now located at the Lagrange point known as L2, which is a gravitational equilibrium point on the shadow side of Earth about 1.5 million kilometers away. L2 is useful because it provides a gravitationally stable location protected from the heat of the Earth and the Sun. It’s a popular location for telescopes, currently also used by Gaia and JWST. Past telescopes such as WMAP and Planck have used the site, and it will be used for future missions such as the Nancy Grace Roman telescope.

The primary goal of Euclid will be to create a 3-dimensional map of the cosmos. In this case, 3D is not length, width, and breadth, but rather galactic latitude, longitude, and time. It will map more than a billion galaxies, plotting their position and redshift, thus giving us a dynamic picture of the universe. From this, astronomers will be able to study the clustering effects of dark matter, the cosmic expansion of dark energy, and how cosmic structure has changed over time. It will be the largest and most detailed survey of the deep and dark cosmos ever done.

We’ve made ground-based galaxy surveys before, such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), but Euclid will gather images four times sharper than previous surveys. It will also observe more distant galaxies, mapping redshift distances as far as 10 billion light-years. Euclid will also gather infrared spectra of more than 100 million stars and galaxies, giving us a better understanding of their chemical composition. Its initial mission will last six years, though that is likely to be extended.

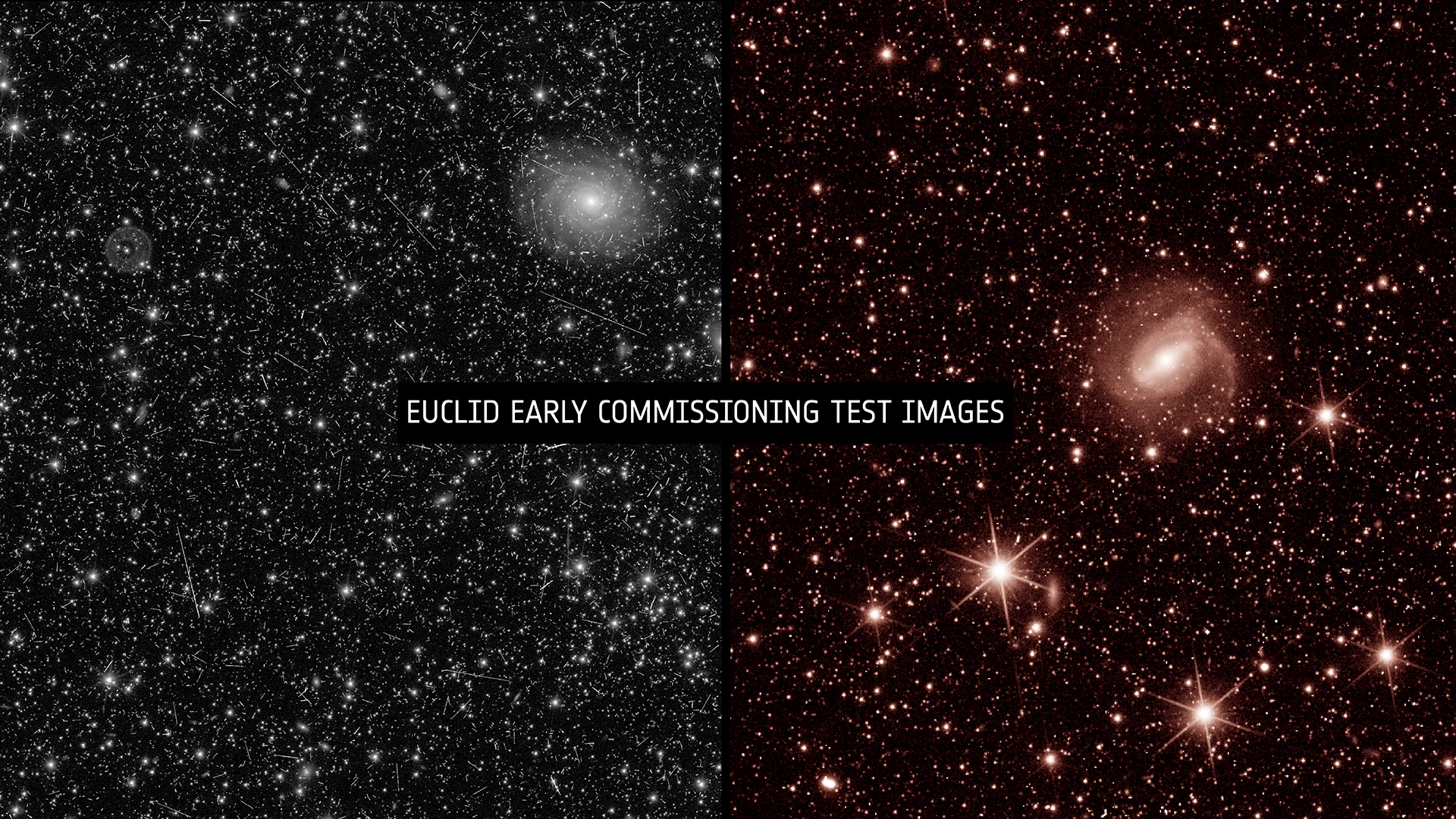

These first images are rough, but they are already impressive. In the image above, the left was taken by the VISible instrument (VIS), and the right by the Near-Infrared Spectrometer and Photometer (NISP). Each image is about 7 arcminutes across or more than a dozen moon-widths. Once these images are calibrated and fully processed, the real data will flow, and astronomers will have yet another tool to explore the heavens.

It’s an exciting time for astronomy, and telescopes such as Euclid will surely transform our understanding in amazing and unexpected ways.

If you want to keep up with the latest Euclid news, check out ESA’s Euclid blog.

What are all the straight lines in the image on the left? It seems like too many and too much spread in direction and location to be asteroids.

Good question! From the article link link to the description of the teste images:

“It is worth noting once more that these snapshots – beautiful though they are – are still early test images, taken to check the instruments and review how the spacecraft can be further tweaked and refined. Because they are largely unprocessed, some unwanted artefacts remain – for example the cosmic rays that shoot straight across, seen especially in the VIS image. The Euclid Consortium will ultimately turn the longer-exposed survey observations into science-ready images that are artefact-free, more detailed, and razor sharp.”

Without any atmosphere to shield it, the image sensors are subjected to cosmic ray hits that among other things show up as streaks in the raw processed signals. Apparently there are ways to eliminate artefact streaks, AFAIU including new efficient algorithms inspired by how the growing low Earth orbit satellite constellations interfere in a similar manner with long exposures in optic astronomy around dawn.