Methanol is one of our most extensively used raw materials. It's used as a solvent, a pesticide, and in combination with other chemicals in the manufacture of plastic, clothing, plywood, and in pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals.

It's also used as a fuel.

The methanol molecule is centred on a carbon atom and has the formula CH3OH. It mostly comes from natural gas and shale gas, a form of natural gas containing mostly methane. But it's expensive to produce and releases harmful emissions.

A team of researchers led by Professor Xingbo Liu at Western Virginia University is working on a technology that can harness carbon from air exhausted from office buildings and use it for a more ecologically sound method of producing methanol. If successful, their system would also remove a harmful greenhouse gas.

The Department of Energy thinks their work is important. The DOE has awarded the project a Phase 1 grant of $400,000. The Phase 1 awards allow researchers to focus on the feasibility, technical merit, and commercial potential of their project.

Most commercial buildings have roof-top HVAC systems. So do many residential buildings. The WVU system would connect to these HVAC systems and extract the carbon from the air that the heating and ventilation systems suck out of the buildings.

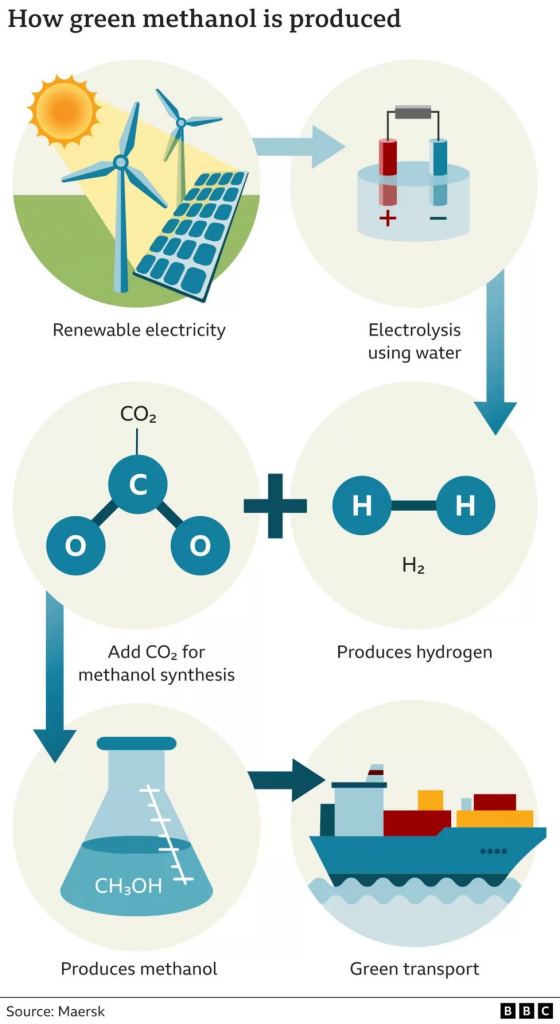

The system has another advantage too. It can use rooftop solar power—a carbon-free energy source—to extract hydrogen from water vapour in the exhausted air. At that point, the system could use a catalyst to combine the carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen into methanol. The methanol would be in liquid form and ready to transport.

Methanol is in high demand because it has so many uses. According to Professor Liu, the demand will only grow, especially as a fuel.

"Methanol also has the potential to be useful in transportation," Liu said. "Now, when you go to the gas pumps, you often have the option for 'flexible fuel,' which is gasoline mixed with ethanol. Well, you can do something very similar with methanol, replacing the ethanol in a gasoline blend."

Methanol in vehicle fuel has some advantages and has been used as a commercial gasoline fuel additive since the 1980s. It's a high-octane component in fuel, which means it's stabilized and predictable and combusts precisely. It's also clean burning. It's also corrosive, which is why it's used as an additive.

Some of the elegance in this system lies in its energy source. It uses heat from the HVAC system as an energy source, making the system inexpensive and inefficient.

"If you have an air conditioning system that's located on the ground outside your building, you stay away from it in summer because it's so hot, right? Really, they provide cold air in the building by making more hot air outside, through waste heat." Liu explained. "So now we can use that to our advantage, because the system we're developing needs that heat."

Liu's system is like a scaled-down version of something used in power plants. Those systems are called point-source carbon capture systems, and they can be expensive and complicated. They're used in gas-burning and coal-burning electrical power-generating facilities, which release lots of carbon dioxide every day.

But most commercial and residential buildings produce far less carbon, so a smaller, more energy-efficient system can do the job. Liu said his system should be cheaper, easier to operate, and easier to maintain. Those things are all critical for widespread use.

"We're working toward a highly integrated and optimized process with state-of-the-art technologies for direct air capture, electrolysis and methanol synthesis that will lead to cost-efficient production of green methanol that's more than 99.7% pure," Liu said.

"We hope to bring down the cost of technology for carbon dioxide reduction and provide a carbon-neutral solution for producing this common chemical, maximizing the use of captured carbon dioxide and minimizing the environmental footprint."

Space missions develop technologies that spawns technical innovation for everyday things on Earth. Things as diverse as scratch-resistant lenses, memory foam, and smoke detectors were all spawned by space travel.

Liu's carbon capture system could reverse that. Could it be used in space?

The International Space Station has to handle its air carefully. As astronauts exhale inside the station, they release carbon dioxide. It's captured by spongy zeolites, a family of microporous minerals that act as molecular sieves. When exposed to the vacuum of space, the zeolites release the carbon dioxide.

But the ISS isn't the best lens through which to view the issue. It gets regularly re-supplied from Earth, and that close connection has allowed NASA and their partners to perfect their zeolite systems over time.

But on missions to the Moon, Mars, or even further, that discarded carbon could be a squandered resource. On average, a human being exhales slightly more than 1kg (about 2.3 pounds) of CO2 each day, depending on activity level. About one-third of that is carbon, which means that a crew of seven astronauts on the ISS is exhaling about 2.3 lbs of carbon each day.

Long-duration space flight or Lunar or Martian colonies will require closed-loop systems like Liu's. The carbon would have to be used instead of discarded. Expand the carbon calculation to a larger crew, and it starts to look advantageous. All that carbon could create a usable amount of fuel. If Liu can also develop a system of combining carbon with oxygen and hydrogen into methanol, then the station or colony would have a source of energy-dense fuel.

Closed loop systems will be integral to future space travel or long-duration visits to the Moon or Mars. The ESA built and tested their Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS) on the ISS's Destiny Module. The ACLS traps carbon dioxide from exhaled air and then processes it inside a reactor to create methane and water. The ACLS vents the methane into space since it's not needed on the ISS. It recycled half of the station's carbon dioxide during its operation. Since some of the crew's oxygen comes from water split apart by electrolysis into oxygen and hydrogen, it generated about half of the water needed on the ISS for oxygen during its operation.

From a certain perspective, the Earth is a closed-loop system, with the exception of the Sun's energy input. There's only a certain amount of carbon and other chemicals. When too much carbon builds up on the wrong side of the atmospheric equation, it affects habitability. NASA says that within the next few decades, some parts of the Earth, especially around the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, could become too hot for humans to live in.

Maybe the system Liu and his colleagues are working on can help balance the equation.

Universe Today

Universe Today