The ESA launched Gaia in 2013 with one overarching goal: to map more than one billion stars in the Milky Way. Its vast collection of data is frequently used in published research. Gaia is an ambitious mission, though it seldom makes headlines on its own.

But that could change.

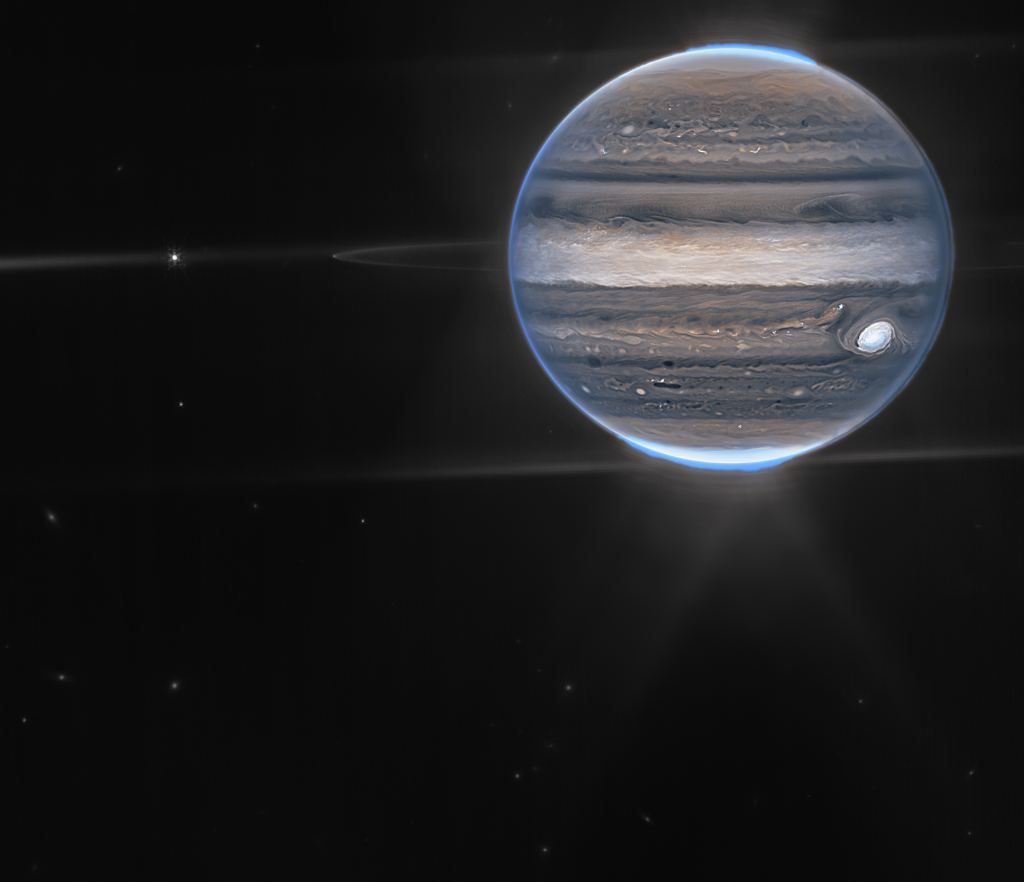

Gaia relies on astrometry for much of its work, and astrometry is the measurement of the position, distance, and motions of stars. It's so sensitive that it can sometimes detect the slight wobble a planet imparts to its much more massive star. Gaia detected its first two transiting exoplanets in 2021, and it's expected to find thousands of Jupiter-size exoplanets beyond our Solar System.

But new research takes it even further. It shows that Gaia should be able to detect Earth-like planets up to 30 light-years away.

The new paper is " The Possibility of Detecting our Solar System Through Astrometry," and is available on the pre-press site arxiv.org. It has a single author: Dong-Hong Wu from the Department of Physics, Anhui Normal University, Wuhu, Anhui, China.

Astronomers find most exoplanets with the transit method. A spacecraft like TESS monitors a section of the sky and looks at many stars at once. When a planet passes between us and one of the stars, it's called a transit. It creates a dip in starlight that TESS's sensitive instruments can detect. When TESS detects multiple, predictable dips, it signifies a planet.

But that's not the only way to detect them. Astrometry can do it too, and that's Gaia's way.

Astrometry has an advantage over other methods. Gaia can more accurately determine an exoplanet's orbital parameters. This doesn't mean the other methods aren't valuable. They obviously are. But as the paper's author explains, "Neither the transit nor radial velocity method provides complete physical parameters of one planet, and both methods prefer to detect planets close to the central star. On the contrary, the astrometry method can provide a three-dimensional characterization of the orbit of one planet and has the advantage of detecting planets far away from the host star." Astrometry's advantages are clear.

If other technological planetary civs exist—and that's a big if—then it's not outrageous to think they have technology similar to Gaia's. While Gaia is impressive, there are improvements on the horizon that will make astrometry even more precise. The author asks a question in his paper: If ETIs (ExtraTerrestrial Intelligences) are using advanced astrometry equal to or even surpassing Gaia's, "...which of them could discover the planets in the solar system, even the Earth?"

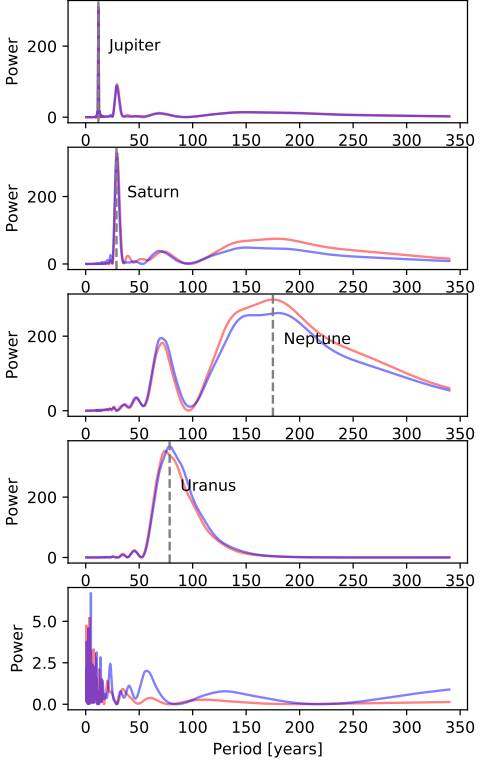

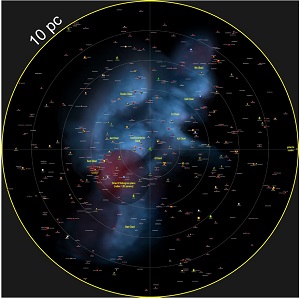

Astrometrical precision is calculated in microarcseconds, and precision decreases with distance. The ESA says that Gaia can measure a star's position within 24 microarcseconds for objects 4000 times fainter than the naked eye. That's like measuring the thickness of a human hair from 1000 km away. But that's not precise enough for Wu's scenario. His work is based on even more advanced astrometry, the type we'll likely have in the near future. "If the astrometry precision is equal to or better than ten microarcseconds, all 8,707 stars located within 30 pcs of our solar system possess the potential to detect the four giant planets within 100 years."

This is the heart of Wu's paper. The 30-parsec (approx. 100 light-years) region contains almost 9,000 stars, and if an ETI from one of those stars has powerful enough astrometry, then it could detect Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The only drawback is they'd have to observe our Solar System for nearly a century to make sure the signal was clear.

There are 8707 stars within 100 light-years of the Sun according to the Gaia Catalog of Nearby Stars. An ETI on any one of them could detect the four giants, as long as their precision is within ten microarcseconds. The precision expressed in microarcseconds is key here, and if the observational error is too large, it has a huge effect and drastically shrinks the number of stars close enough. "If the observational error is as large as 100 microarcseconds, only 183 neighbouring stars could detect all four giants, but all of them could detect Jupiter within ten years," Wu explains.

Detecting Jupiter from a distance could be a critical threshold. When Gaia released its first data set in 2016, an ESA paper discussing the mission touched on exoplanet science and the importance of detecting Jupiter-mass planets. It's based on the idea that Jupiter may have played a protective role by deflecting asteroids and comets away from the planets in the inner Solar System. "These are logical prime targets for future searches of terrestrial-mass exoplanets in the habitable zone in an orbit protected by a giant planet further out," the paper states.

ETIs might know things about solar systems that we don't know. To them, finding gas giants in the outer regions beyond a solar system's asteroid belt might be a strong signal that rocky planets are closer to the star. Maybe they'd be curious and want a closer look.

Where it really gets interesting is when it comes to our own planet. Could ETIs detect Earth using astrometry?

That, again, depends on microarcsecond accuracy. "Additionally, our prediction suggests that over 300 stars positioned within ten parsecs from our solar system could detect our Earth if they achieve an

astrometry precision of 0.3 microarcseconds," Wu writes. Technological barriers stop us from achieving this for now, but who knows what an ETI's technological level might be?

Now turn this idea around with our own technological advances in mind.

The ESA is already discussing a successor to Gaia. They call it GaiaNIR, and it would expand Gaia's search into objects only visible in the infrared. If built and launched, it would not only measure IR targets, it would revisit Gaia targets again to further increase the accuracy of Gaia's existing data.

GaiaNIR's improvements would open up "new science cases, such as long-period exoplanets," according to one paper. Long-period planets are difficult to detect with the transit method because you have to watch a star for a long time. For example Neptune with its 165-year orbit. With GaiaNIR's improved technology, and even more improvements in the future, we could be the ones detecting Earth-size planets in a 10-parsec radius.

Astrometry is an improvement over the transit method because the transit method only works when things line up just right. An exoplanet must pass between us and its star before we can detect the dip in light. But Gaia's astrometry doesn't have the same limitation. It can watch a star from any angle to detect planet-induced wobbles.

How technologically advanced would an ETI have to be to detect Earth with astrometry? Are there any ETIs within 10 parsecs? 30 parsecs? 100 parsecs? Are there any ETIs at all?

Who knows.

But we're hungry for Earth-sized exoplanets, and this research shows how Gaia may be able to satisfy our appetite. If it does, it might generate more of its own headlines and get some of the attention other missions regularly attract.

Universe Today

Universe Today