There may come a day when we grow weary of JWST images. But it's not today. Today, we can lose ourselves in the space telescope's engrossing image of NGC 6822, also called Barnard's Galaxy.

Barnard's Galaxy was discovered by the accomplished American astronomer E. E. Barnard in 1884. He spotted it with a 6-inch refractor telescope. It's the closest galaxy to the Milky Way that isn't a satellite galaxy, and it's quite similar to our neighbour, the Small Magellanic Cloud. It's a dwarf irregular galaxy about 7,000 light-years across and about 1.6 million light-years away.

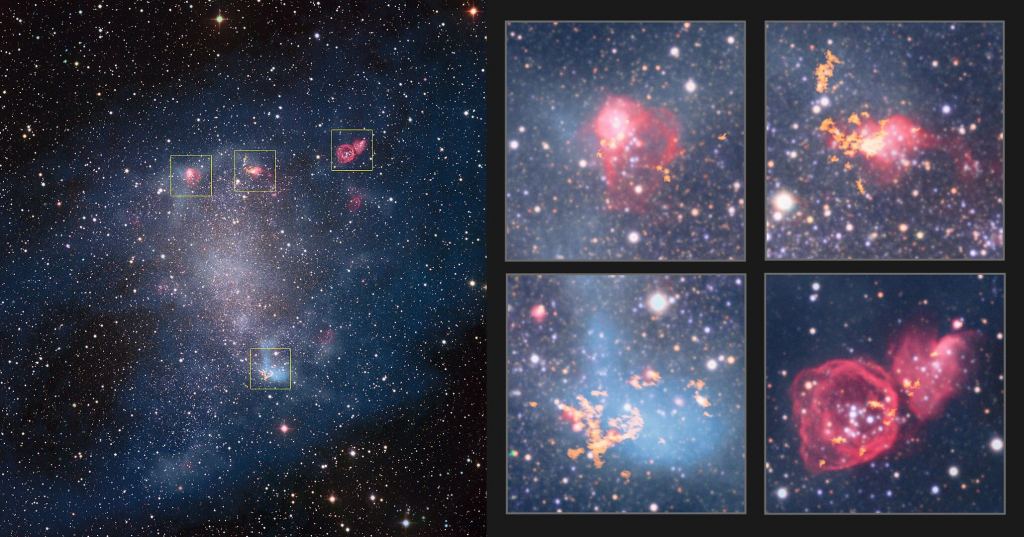

The JWST captured this image with its NIRCam instrument, and it shows the galaxy in deep detail. Dust and gas are pervasive in the galaxy, but the JWST has the power to see right through it with its infrared instruments. One of the reasons JWST was built was to peer through gas and dust and see what's going on behind it.

Zooming in reveals the JWST's power. Here and there, distant galaxies pop into view well beyond Barnard's Galaxy.

Webb doesn't take colour pictures, so when it sends data back to Earth, it's all black and white. But it does an excellent job of capturing photons, and the images are processed into colour for our enjoyment and for scientific detail. In the image, the brightest stars are blue and cyan, while the fainter stars are warm-coloured.

The little bit of gas and dust visible in the image is also a testament to the JWST's power. Gas and dust pervade the galaxy, but in this image, only a small amount is visible.

The JWST team published another image of NGC 6822 last summer. That image was captured with both the NIRcam and MIRI instruments. It highlights the space telescope's power and the flexibility it gains from its multiple instruments and filters.

Barnard's Galaxy is a bit of a puzzle. Its oldest stars are 10 billion years old, and some research suggests they're even older. But most of the stars in NGC 6822 formed in the last 3 to 5 billion years. It's been isolated for most of its life, but some research shows it came close enough to the Milky Way in the last 3 or 4 billion years to trigger star formation. The star formation rate may have accelerated even more in the last 100 to 200 million years.

Overall, the stars in NGC 6822 have low metallicity, meaning they're mostly made of hydrogen and helium and almost nothing heavier. All stars in the early Universe had low metallicity because elements heavier than hydrogen and helium can only be forged in stars. When the stars die, the metals are spread back out into the Universe, to eventually form new stars with higher metallicity. Astronomers are greatly interested in contemporary objects with low metallicity, like NGC 6822. Studying it helps astronomers gain insight into the cycle of interstellar gas as it's taken up in star formation and then expelled back into the interstellar medium. It also helps them understand how stars evolve.

NGC 6822 has a place in astronomical history. It was the first object that astronomers were certain was outside of the Milky Way. We take that for granted now, but at the time, there was a raging debate about the size of the Universe, and astronomers weren't certain there were any objects outside the Milky Way.

Famous American astronomer Edwin Hubble studied it extensively and published a paper on it in the Astrophysical Journal in 1925. "NGC 6822 is a faint irregular cluster of stars with several small nebulae involved," Hubble wrote. "NGC 6822 lies far outside the limits of the galactic system."

The JWST was a long time coming. It's development was a highly-contested affair sometimes, and Congress threatened to cancel it. But it stands as the pinnacle of astronomical achievement, and now that it's operating, it's expanding and deepening our understanding of the cosmos, and of nature.

With gorgeous images like this one of Barnard's Galaxy, we're all along for the ride.

Universe Today

Universe Today