Now that several decades have passed since the launch of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 in 1977, we look back on that time with a hazy sense of history and what the event meant for humanity's ongoing odyssey. While the Voyager spacecraft were sober scientific missions, they also carried with them a hint of the deeper yearnings that lie inside humanity's heart: the Golden Records.

The Voyager Golden Records were a message in a bottle to any other intelligent species out there that may stumble on them. While the odds are strongly stacked against that ever happening, the Records still served a purpose. They showed that we're driven not only to understand the Universe but that we're open to understanding other intelligences and that we desperately want to be understood ourselves. They also showed that we want to be unified with one another. The Golden Records are a verse of poetry among all the science.

Carl Sagan was instrumental in selecting material for the Golden Records, and he probably said it best: "The spacecraft will be encountered, and the record played only if there are advanced space-faring civilizations in interstellar space, but the launching of this 'bottle' into the cosmic 'ocean' says something very hopeful about life on this planet."

The Golden Records contain both sounds and images that encapsulate aspects of life on Earth. It's a time capsule containing natural sounds of Earth's weather and wildlife, humans speaking in 55 different languages, and printed messages from political leaders of the time. It also contains a large assortment of images, from a magnified look at the structure of DNA to an Ansel Adams photograph of the Snake River and the Grand Tetons.

Both Voyager spacecraft have left the Solar System behind now and are in interstellar space. The records are with them, and it's almost certain we'll never know what happens to the spacecraft or the records. But that doesn't mean the effort was wasted. In fact, some people are already thinking of what we can put on the next message in a bottle (MIAB) we send out into the vast Universe.

In a research article published in AGU Earth and Space Science, a team of researchers investigated what our next MIAB should look like. The article is titled " Message in a Bottle—An Update to the Golden Record: 1. Objectives and Key Content of the Message. " The lead author is Jonathan Jiang, a scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

"These records not only offer a snapshot of Earth and human civilization but also represent our desire to establish contact with advanced alien civilizations," the authors write. "Our goal is to share our collective knowledge, emotions, innovations, and aspirations in a way that provides a universal, yet contextually relevant, understanding of human society, the evolution of life on Earth, and our hopes and concerns for the future."

Thoughtful people will intuitively understand this. But here's the difficult part that evades intuition: we can't know who we're sending it to and what symbolism and semiotics might make some sort of sense to them. We have to reach some sort of workable conclusion to that.

To do that, we need to imagine our audience as best we can. There are so many vexing questions in this that we're forced to assume they're similar to us in at least some respects. "It is entirely possible that concepts such as "civilization" may not apply in a meaningful way to an alien intelligence, but in order to proceed, it is necessary to assume an alien intelligence that will be in some way like us and can make sense out of our attempts at communication." There's no other way to proceed.

The article lays out some of the rationale for sending more MIABs into space and what types of fates await them, from interception by a highly advanced ETI to an eternity drifting through empty space. Then the authors drill down on the central question: What should we put into the time capsule?

The authors write that some of the original record's content was so well thought out that it could be modified and used again if updated to reflect current technology and times. But some of the content and messaging contained imperfections and difficulties that need to be corrected. "In short, the content of the updated record will not only serve the purpose of more sophisticated redundancy but will bear the timeline of human civilization from the ancient past to the latest present and possible causes of our ascension (or extinction) into the future," they explain.

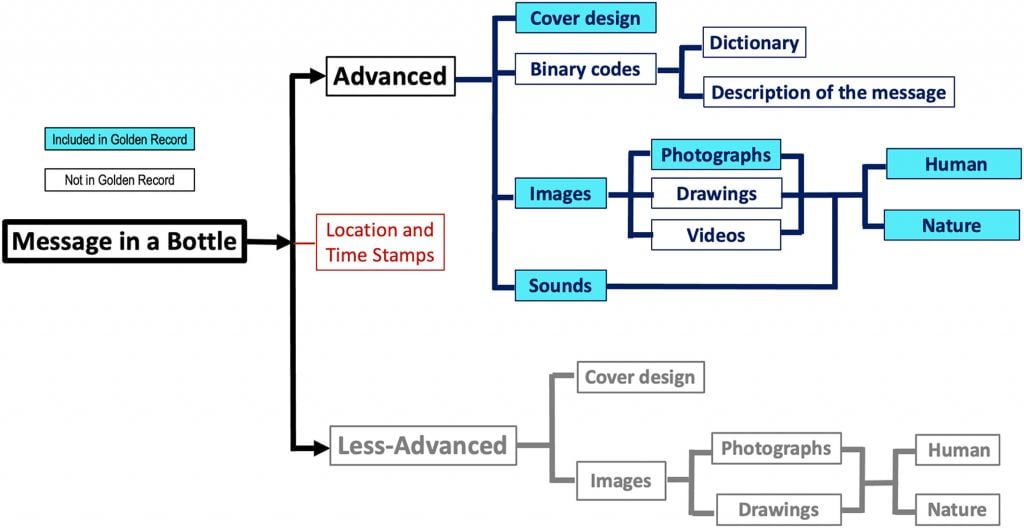

The authors propose a two-part message: a scroll containing simple images that illustrate basic information about humanity and Earth and a small minicomputer that can contain vast amounts of digital information. The scroll is intended for less advanced recipients, and the minicomputer is intended for more advanced recipients.

If an ETI does receive one of our time capsules, two questions will likely occur to them fairly quickly. Where are we from, and when are we from?

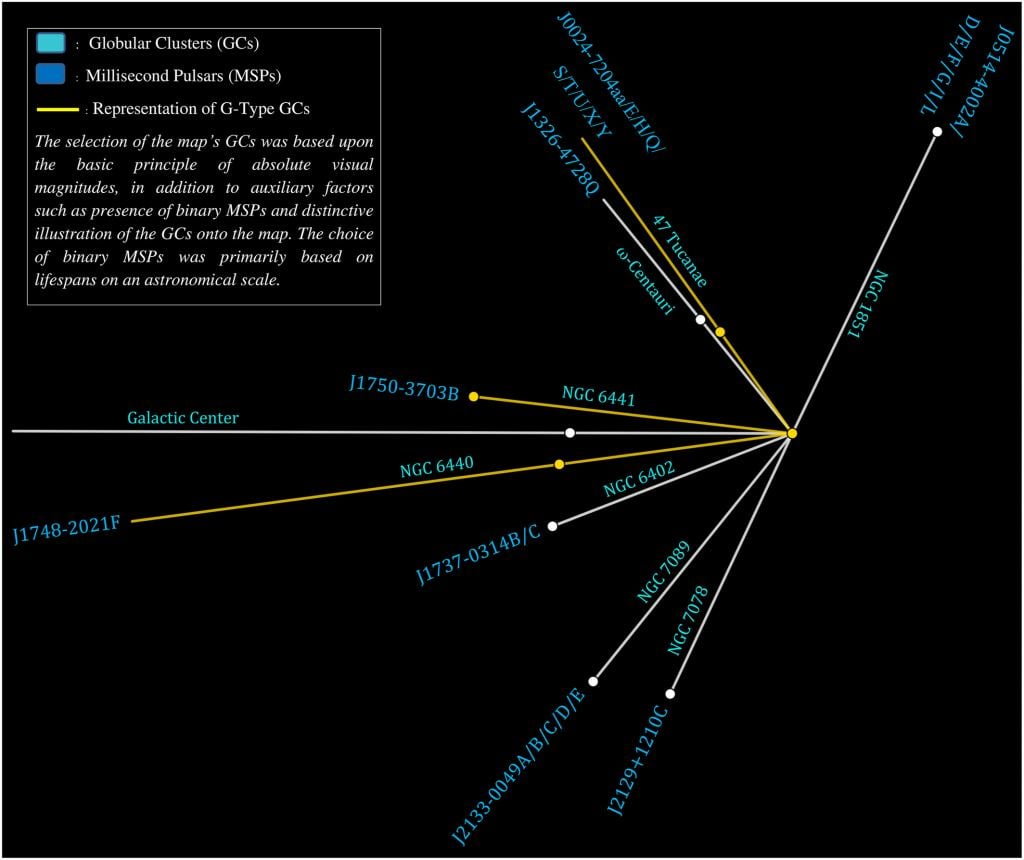

For an advanced recipient, one of the main things is to tell them where we're at in this vast galaxy and Universe. That can be done with an image of some of the brightest objects in the galaxy and where we are in relation to them. It can be based on things like Globular Clusters and Millisecond Pulsars (MSPs.)

The second question they might like an answer to is, when was the MIAB launched? Due to the changing nature of the Universe, our explanation of where we're from is dependent on the recipient knowing when we launched it. "In general, due to the substructure evolution in the galaxy, it is critical to specify the design and launch time of the proposed location map," the authors explain. "Otherwise, though future life may decode the map successfully, they would not necessarily realize the timeline of human existence and, as a consequence, will not be able to manifest the galactic scenario at a specific time in the past."

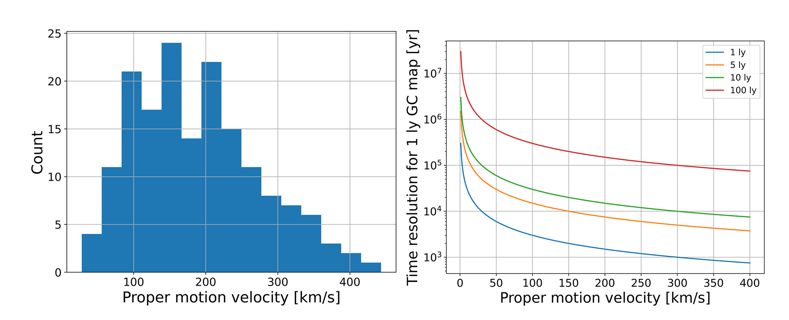

The authors say that they can give the image of GCs and MSPs a timestamp by including the proper motion velocities of the GCs.

The panel on the left shows the distribution of 164 globular clusters' proper motion velocity. The panel on the right shows the time resolution for the map of the GCs and MSPs. Image Credit:

This paper is the first in a series that will discuss what should go on the new Golden Records. They don't name specifics at this stage but do point out some of the overarching concepts. Along with a map telling any recipients where and when the MIAB was launched, the authors flesh out some of the thinking that will guide specific inclusions.

"Audio will not only include sounds from our natural surroundings but also incorporate music and a myriad of others commonly encountered in our lives along with impressions of the modern and technologically advanced societal structure of which we are all a part," they explain. "Considering a generally similar approach to that opted for in the content selection of the Voyager Golden Records, we shall as well suggest modifications while also including the most relevant content spanning the two generations which have elapsed."

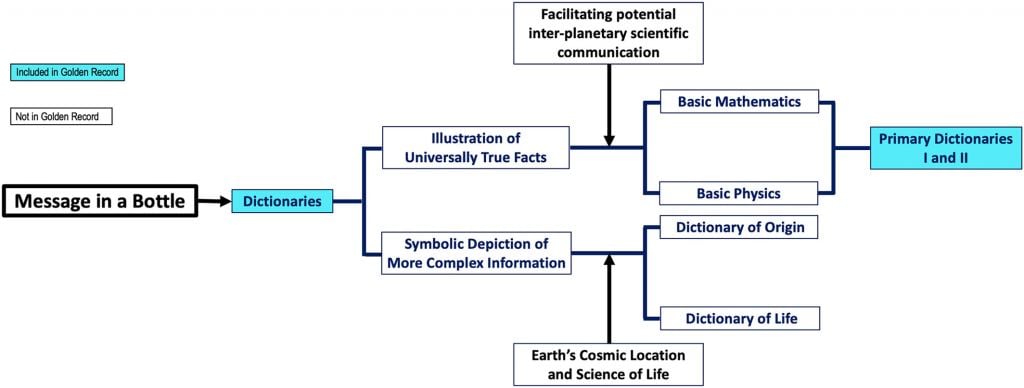

Three organizing ideas should shape the content. One is the origin of the record, and the GC and MSP map should explain that. The second idea is an answer to the question, "Who sent it?" The third guiding idea is probably the most important: a detailed overview of our nature. That one, perhaps, will generate the most discussion.

The authors think we should show any recipients the long history of life on Earth and how evolution built us and our civilization. We should show them some of the bleakness, like our terrible wars. But we should also show them our triumphs. "Encompassed within this description are our scientific achievements, such as splitting the atom and space exploration, along with examples of a wide array of cultures and knowledge which comprises the complex human tapestry," they write.

The MIAB should also look to the future. They describe it as a testimonial from our world to any others out there. "To fulfill this role, an encapsulation of who we are in the present must also extend to visions of what we might become—in short, examples of human aspirations."

But just as important as tailoring the contents to an eventual recipient is the effect it has on us, the senders, and what it means for us.

"Through this time and space travelling capsule, we also strive to inspire and unify current and future generations to celebrate and safeguard our shared human experience." We're at a point in our evolution where we can easily imagine our own extinction, either by nature's hand or our own. This exercise of reaching for the future and reaching for other intelligences is part of what helps us face our own uncertain future.

Whether we embrace it or not, we're all part of humanity's journey. The future is always uncertain. But if we have any chance of guiding ourselves into the future, endeavours like this can be part of it.

Universe Today

Universe Today